A detail from the cover of 'The Forde Collection', recently published by the Irish Traditional Music Archive – Nathaniel Grogan's 'Dry Bridge at Blarney', c. 1790 (Located at Fota House, Co. Cork; courtesy Irish Heritage Trust)

Cultural Treasures Bound up with Barbarism

In August of 1846, amidst the total collapse of the Irish potato crop, with millions of acres of smallholder plots giving off the intolerable stench of rotten tubers, William Forde, the Cork-born flutist, composer, arranger, music collector and publisher, travelled from Dublin to Leitrim in search of melodies. That month, Father Theobald Mathew, the famous ‘apostle of temperance’, wrote of his own passage from Cork to Dublin: ‘I beheld with sorrow one wide waste of putrefying vegetation. In many places the wretched people were seated on the fences of their decaying gardens, wringing their hands and wailing bitterly at the destruction that had left them foodless.’ (Donnelly, 2013, p. 57) In early September, Forde had found and made the acquaintance of the piper Hugh O’Beirne, near Ballinamore, County Leitrim. From there Forde wrote to fellow Corkonian John Windele, well known in antiquarian circles for his theory, based on the discovery of human skeletal remains at the base of one of them, that Irish round towers were sepulchral hero-monuments. (The presence of the skeletal remains were subsequently proven to be a grave-digger’s prank.) Forde wrote:

Here I have found a Piper, Hugh Beirne, who has given me about 150 airs – no jigs but all Airs – meeting him has detained me here longer than convenience warrants – for, no music without having a hand in the pocket… The piper H.B. has been dying for the last 2 or 3 years, but while ensuring the life of the Airs that w’d have perished with him, I do believe I am the means of giving him life also. Stirabout and bad potatoes were working fatally on a sinking frame – but a mutton chop twice a day has changed Hugh’s face wonderfully. If I may risk a Hibernicism, I have thus killed two birds with one stone. (emphasis in original)

This extract is reproduced in the introduction to Nicholas Carolan and Caitlín Uí Éigeartaigh (eds), The Forde Collection: Irish Traditional Music from the William Forde Manuscripts (p. xl), published last year by the Irish Traditional Music Archive (ITMA). With astonishing reticence, Carolan comments that this was ‘remarkably’ the only oblique reference in Forde’s correspondence to the historic disaster unfolding in the countryside he was traversing, and that this ‘provides an insight into the lived reality of the time.’ (p. xl) Indeed, it provides insight into multiple realities of the time: the reality of the shared outlook of two members of the Protestant antiquarian intelligentsia, the reality of a peasant musician with a seemingly bottomless repertoire of song airs but who like hundreds of thousands of others was slowly starving to death for lack of food or means of support, and the intersection of these realities in this brief and deeply ambivalent relationship by which the inconvenienced antiquarian, with a shrinking store of money in his pocket and ready access to a supply of meat (held perhaps by the local hotelier or the military garrison that sponsored his stay), literally kept the piper alive for the sake of preserving about 180 tunes, a few dozen of which had already been published by others, a few dozen more trifling song melodies well preserved in the wider oral tradition, and, surely, some true treasures of the oral musical culture that may well have ‘perished with him’.

Is it possible to avoid profound feelings of anguish, despair and sadness while exploring material collected and preserved in these circumstances? Do the pages before us not present disconcerting corroboration of the reflections of the German cultural critic Walter Benjamin about cultural treasures on the eve of the outbreak of another great human catastrophe, the Second World War? Benjamin argued that historical experience must be rooted in empathy and despair for the losers, and that our so-called ‘cultural treasures’ be experienced with care and historical awareness. For Benjamin, this requires that received textbook histories be ‘brushed against the grain’ so that the painful ambivalence of the lived realities congealed in these treasures be brought to light. For the authentic historian:

… Without exception the cultural treasures he surveys have an origin which he cannot contemplate without horror. They owe their existence not only to the efforts of the great minds and talents who have created them, but also to the anonymous toil of their contemporaries. There is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism. And just as such a document is not free of barbarism, barbarism taints also the manner in which it was transmitted from one owner to another. A historical materialist therefore dissociates himself from it as far as possible. He regards it as his task to brush history against the grain. (Benjamin, p. 256)

What was the lived reality of this ‘classical’ musician, who so casually and callously equated the ‘life’ of tunes like ‘Een, Been, Bubbero!’ and ‘Ree, Ro, Raddy O!’ (numbers 765 and 766 in the collection) with the life of a fellow human being, a fellow musician, and a fellow Irishman? What was the lived reality of this peasant piper, so reduced in circumstances, destined to starvation if not for this happenstantial encounter? And how, in the end, are we to engage as musicians with these treasures so bound up with barbarism?

Long awaited

These are some of the questions provoked by Nicholas Carolan’s introduction to the massive The Forde Collection, a volume that contains over 900 transcriptions of Irish tunes and songs from an even larger archive amassed by William Forde in the 1840s and held in the library of the Royal Irish Academy. Carolan, Director Emeritus of ITMA and the general editor of its Studies in Irish Traditional Music publication series of which this volume is the latest item, is practically alone working in the field of the historical musicology of Irish traditional music, having a number of projects dealing with collectors of Irish music from the eighteenth to the twentieth century either completed or in progress in a long and hopefully long-continuing career. Uí Éigeartaigh, who completed a thesis on the collector Patrick Weston Joyce (a late nineteenth-century collector who had possession of the Forde manuscripts) in the 1960s, has had this project of transcription and transposition in her hands for many years. It is an understatement to say that for those of us with personal and professional interest in this material this volume has been ‘long awaited’, and no exaggeration to say that the historical musicology of Irish traditional music in recent decades, going back to the 1960s, has been poorly organised, underfunded and haphazard in its progress. This is no criticism of the editors of the The Forde Collection, who have produced a marvellous volume with an introduction by Carolan giving a detailed account of Forde’s life, and the life of his manuscripts after his early death in 1850 at the age of 53, another introduction by Uí Éigeartaigh explaining her editorial procedures, and valuable appendices, bibliographies and indexes. However, this project is not what or when it might have been, had it been properly supported in the context of a higher education research programme in an Irish university. But such a research programme has never existed in any Irish university, even those with programmes devoted specifically to Irish traditional music, obsessed as they are with performance practice and critical thinking which is for the most part ahistorical in focus. The result is that today we have a superfluity of practitioners who know how to play, but are lacking in understanding of what they are playing and how it came to be. And we must accept that the progress of this academic field will remain, as it has been for decades, mainly in the hands of passionate individuals who make their living in other ways and have limited time and resources.

Forde was born 1797, the son of an eminent Cork Protestant businessman who through unspecified ‘negligence’ lost his business, abandoned his family, and fled to America while Forde was still a teenager. With musical training and precocious talent Forde became a noted performer on the flute in Cork ‘classical’ music circles, and helped support his family as a music tutor, while still a young man. He was to have a remarkable career that was nevertheless plagued by a precariousness rooted not only in his family misfortune but also in the declining state of Irish elite musical culture through which he navigated. As has been discussed by the present writer and a number of Irish musicologists, the rich inheritance of Irish eighteenth-century elite musical culture began an irreversible decline in the wake of the Act of Union. During Forde’s lifetime that culture fell irreversibly behind not only the London scene, but also behind other peripheral national musical cultures. Musicologist Harry White compared Ireland to Hungary and Poland, where distinctive elite musical cultures were erected on top of a plebian base in the nineteenth century, perhaps unfairly considering the lack of investment in Ireland in the infrastructures required. So in Ireland preoccupation with preserving the musical antiquity in the heads and hands of Irish peasants appeared to have almost completely displaced creative musical production (Dowling, pp. 156–60). The regressive milieu is reflected in Forde’s dependence on London for training, for performing and reputation building, for publishing, and for the acquisition of talent as a concert promoter in Cork. It is also reflected in his frenetic hyperactivity on numerous fronts simultaneously: performing, teaching, institution building, concert promotion, lecturing, fundraising for all of this – and dwarfing all of these an incredibly prolific output of published material. The 1830s saw a flood of Forde’s collections published in London of:

Swiss melodies, Italian melodies, Swedish melodies, Scottish melodies, Strauss waltzes, national airs, country dances, psalms and hymns, military marches, polkas, polaccas, canzonets, romances, quadrilles, bagatelles, rondos, preludes, overtures, and beauties of the great composers Berbiguier, Beethoven, Hayden, Mozart and others. (p. xxi)

All this activity brought Forde widespread and celebratory notoriety, but nothing paid very much. Carolan reports an irony that poignantly captures the ambiguities of this milieu. In 1845 while he was being celebrated in Irish newspapers as ‘a born genius’ and an ‘ornament to his city’, he could not keep up with the rent on the Cork lodgings he shared with his wife and had his flute confiscated by a bailiff (p. xxxiv).

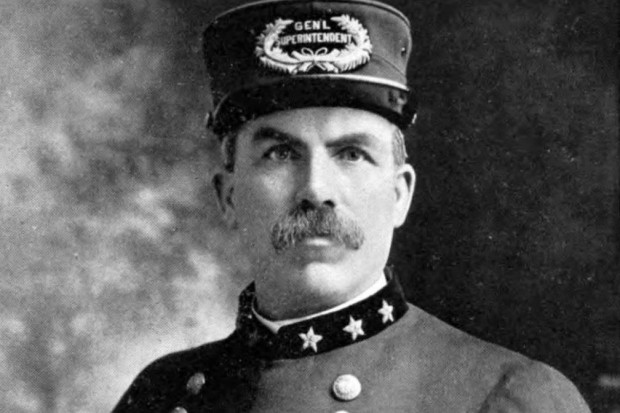

Given his consummate musical skills, his rich experience in the publication of music, particularly vernacular music, and his connections to the activities of the Protestant antiquarian intelligentsia, it is unsurprising, and perhaps inevitable, that Forde would gravitate toward projects involving the collection, analysis and publication of music from contemporary Irish rural oral culture. After all, the 1830s and 1840s had seen the dramatic flowering of ‘scientific antiquarianism’, represented most strikingly by the enormously ambitious and for a time well-funded Ordnance Survey of Ireland, which uncovered a wealth of detail on the cultural habits, including musical ones, of the inhabitants of Ulster in the 1830s. George Petrie, an amateur violinist and superintendent in the Ordnance Survey Memoirs project, was known to be actively collecting music in this period, though his own work would not appear for another twenty years. So as Carolan plausibly suggests, with Edward Bunting having published his swansong third edition of the Ancient Music of Ireland in 1840, the field appeared to be wide open for Forde.

The title page of 300 National Melodies of the British Isles, arranged by William Forde, published in London in 1841 (Image courtesy of the Irish Traditional Music Archive).

Sources

As might be expected, the sources of the music Forde collected in these years map closely onto his social milieu in Cork and London. In Cork he got music from other collectors with whom he shared class and sectarian affinities (brewers, distillers, other literate professional musicians). Similarly in London he received notations from other collectors and musicians, most significantly the sculptor Patrick MacDowell of Belfast who gave him over 150 pieces. London and Cork, and also possibly the routes between them, put Forde into direct contact with practitioners from the Irish countryside such as the singers Fitzgerald from Cork and a Mr E. Flattely from Erris, County Mayo. By the middle 1840s Forde had clearly developed an appetite for hunting down and notating tunes directly from practitioners, and had an eye and ear for pipers around Cork city. Forde described his ‘fieldwork’ strategy to Windele in 1845: ‘To know a country you must not skim over it, but stop in one place for a month & take radiating excursions so as to know the neighbourhood intimately – for national popular music you must come to the people unawares, & lie in wait for it.’ (p. xxvi) In Cork, one place to lie in wait was the shebeens and brothels near the military barracks, where pipers were known to ply their trade. Here Forde found the piper Paddy Carey, from whom he notated three dozen tunes. An invitation from a musical acquaintance, Captain Pratt of the 41st regiment stationed near Ballinamore, County Leitrim, provided him with the place from which he could safely make ‘radiating excursions’ in fresh territory, some as far as south Ulster, and find Hugh O’Beirne near Ballinamore.

How do we understand this man and his musical culture? Carolan provides what detail can be gleaned from the historical record about this piper, but the introduction falls far short of what can and should be said about his lived experience and his relationship to a collector like Forde. The present writer has provided a detailed account of the development of vernacular musical culture in prefamine Ireland into a distinct national tradition, including an exploration of the evidence of that culture deposited in the Ordnance Survey Memoirs and an account of the central position pipers like O’Beirne came to occupy within that culture by the 1820s – all of which is unmentioned and unreferenced in Carolan’s introduction (Dowling, pp. 89–126). Future generations of musicians playing the music of The Forde Collection will not understand what they are playing without some insight into the context of the culture that produced it. This was a culture radically different from the lived experienced of twenty-first-century traditional musicians, particularly regarding how music making was involved in the religious and political controversies raging in Ireland in the decades before the famine. If we are to ‘brush history against the grain’ as musicians, we need more context than is offered in The Forde Collection. With the following paragraphs the reader can make a start.

Cultural and political crisis

The lives of professional musicians of O’Beirne’s generation were scarred by the profound cultural and political crisis into which Ireland was thrown in the midst of the post-Napoleonic deflation of prices and the accompanying contraction of economic opportunity in the countryside. The price collapse, bad weather and blight of crops that occurred in the decade before Catholic Emancipation was begrudgingly passed by the British Parliament in 1829 were devastating enough on their own. This economic collapse occurred in circumstances where, in the wake of the international democratic revolutions, millions of smallholding Catholic peasants had no effective political representation, and the result was a volatile landscape. This was a rural society under extreme stress, and popular reaction to that stress took some extreme and violent forms, such as the infectious popularity of ‘Signor Pastorini’s’ weird prophecy based on the Book of Revelations which, reinterpreted by balladeers, anticipated the extermination of Irish Protestants in the year 1825 (Donnelly, 2009, pp. 119–149; Whelan, pp. 141–152).

The worsening economic conditions exposed the utter fragility of the patronage networks supporting the pipers. While the gentleman piper or elite sponsor appear occasionally in the historical record, there is very little evidence of a coherent culture of musical patronage from the landed elite and their managers in this period, a phenomenon that may have had a variety of causes: animosity founded in evangelical puritanism, a philistinism oriented exclusively to the business of property management, or simply another facet of the absentee’s social distance and negligence. As a result, the livelihoods of the pipers collapsed along with the livelihoods of the smallholders and weavers who supported them most.

The eighteenth-century concept of Protestant Ascendancy, whereby Protestants of the Established Church held exclusive control of Irish government institutions, was once again resurgent in these decades. We know from historian Irene Whelan’s account of this period that this was now being fuelled by the far more ambitious project of Protestant evangelicalism, a crusade launched by the Church of Ireland and backed by significant segments of the landowning class (and particularly prevalent in a belt stretching underneath the Ulster border from Sligo to Louth, in which Captain Pratt’s regiment was positioned). For a powerful and growing segment of Protestant society, monopoly over political power and economic assets was no longer sufficient. It was required to establish a new moral order, requiring the elimination of

not only the Catholic religion and its priests, who kept the population spiritually enslaved, but equally the attitudes and practices accumulated over centuries of neglect, which had given rise to the profligate economic habits of both rich and poor and which were seen as the alarming growth of a redundant surplus population.

The evangelising project was also supported by ‘a rising tide of conservative opinion in Britain as well as Ireland that public funds be used to advance the process’ of re-educating the Irish Catholic peasantry (Whelan, pp. 147, 166, 269).

What stood in the way of this publicly funded programme of exporting surplus population to Canada and Australia and converting those that remained into parsimonious, docile, Bible-reading Protestants was the Catholic Church, which had by the 1820s become strong enough, according to Whelan,

to provide effective resistance to the evangelical mission by laying claim to and finally taking control over the chief agency of modernization, namely, education. More than any other event it was the battle over education that brought the bishops and priests openly into the world of popular politics where they acted as a unifying force behind the campaign for Emancipation.

From the 1820s, ‘the Catholic Church had assumed its role as the protector and defender of the interests of the Irish poor. Its leaders understood the danger implicit in the combination of economic crisis and cultural destabilisation threatened by the evangelical moral crusade [namely, millenarianism and sectarian violence].’ (Whelan, pp. 149, 150) In the 1820s, in close alliance with Catholic Bishops and priests, Daniel O’Connell drove forward the largest political mass mobilisation Europe had ever seen in support of Catholic political emancipation. Through Whelan’s work we see just how close the country came to civil war, and how inadequate the military occupation of the island would be to prevent it (Whelan, p. 146). This was the knife-edged context in which parliament passed a Catholic Emancipation bill in 1829, when the policy of a more accommodating and reformist strand of the Protestant elite, a strand which had existed since the 1770s, was finally established in law. This reformist stance held that

Only those Catholics who could be trusted, that is those who possessed property and education sufficient to warrant their support for the status quo, should be allowed a voice in the political process. The latter might be considered after they had been improved or enlightened to such a degree that they could assume the civic responsibilities fundamental to the modern nation state.

This position was also entirely amenable to O’Connell, who struck the deal in 1829 ‘that if the forty-shilling freehold voters on whose power the entire emancipation movement had been carried forward were disenfranchised, an Emancipation bill would be passed.’ (Whelan, p. 36–7, 232–33)

Below the surface

This was the milieu in which pipers like Carey and O’Beirne practised their art. Much of their music was made out of doors at public gatherings that, if not overtly organised for a political purpose, were rarely without political or religious significance and where sectarian tensions were kept just below the surface. As the main custodians of oral musical culture, their repertoires included the canon of airs and songs from the eighteenth-century Jacobite tradition, the political songs issuing from the 1798 rebellion, and tunes to accompany marching and dancing. Their tunes were lined up, sometimes literally, against the Orange and Loyalist repertoire of the army regiments and yeomanry bands (Dowling, pp. 103–113). In stark contrast to its whitewashed antiquarian reflection, the actual peasant tradition, as Joep Leerssen reminds us, was ‘not just of stories and soothsayings, pookahs and leprechauns, but a tradition of resistance, an eloquent voice against English and Protestant domination.’ (Leerssen, p. 178) To portray it in this way, as James Hardiman did in his Irish Minstrelsy, or Bardic Remains of Ireland (1831), was to provoke outrage from mainstream Dublin antiquarianism (see Leerssen, pp. 177–86, and O’Brien Moran, p. 97 for discussion of this episode).

As public figures the pipers and singers were easily identified by the authorities and by sectarian enemies and their activities came under increasing surveillance in this period. It is not surprising that Captain Pratt of the 41st regiment was able to lead Forde directly to O’Beirne. But in terms of surveillance, by far the most significant development in these decades was the increasingly aggressive control over the outdoor habits of the peasantry obtained by the agents of the Catholic Church. Priests publicly excluded parishioners found to be attending outdoor dances from sharing in the sacrament, forced public confessions from them at mass, or exacted public penance from them at the church door. Ordnance surveyors in Cushendall in County Antrim observed in the 1830s: ‘It had been customary for each pub to hire two pipers or fiddlers on fair days, so that their customers would have music to dance by, but their priest within the last year put a total stop to it.’ And the infamous Casey, parish priest of Ballyferriter on the Dingle Peninsula in the prefamine decades, a ‘deadly enemy of pipers’, was not the only priest known to destroy instruments and outdoor dance floors, violently attack pipers, and break up dances and parties (Connolly, pp. 123, 168, 177, 183; Dowling, pp. 132–5). From the pipers’ perspectives, the ‘Bible War in Ireland’ was therefore not so much a battle between puritanical Protestant evangelicals and an untamed native culture as a battle between the Church of Ireland and the Catholic Church over which institution would tame and control that culture. The pipers were by the 1840s caught in multiple crosshairs of surveillance, politically disenfranchised by Catholic Emancipation, their position one of severe economic vulnerability and, with the onset of famine in 1845, many were facing their own extermination.

The elite antiquarians of the 1830s and 1840s, those in charge of the Ordnance Survey, members of the Royal Irish Academy, etc., are often celebrated as the representatives of an enlightened and progressive tendency within an otherwise politically regressive Irish Protestant elite society. When the government cut off funding for the Ordnance Survey project in 1840, the Dublin press defended it in terms reminiscent of Troubles-era cross-community projects. An 1844 article in Dublin University Magazine concluded optimistically:

Is it not a delightful spectacle, now perhaps for the first time exhibited in Ireland, to see Irishmen of all parties and creeds, the most illustrious in rank and the most eminent in talent, combining zealously for an object of good to their common country? And may we not take it as an auspicious omen of the happiness and peace yet in store for us, and which must follow as an inevitable result of the continuance of a unity thus happily begun? (Leerssen, p. 105)

Carolan applies a similar idea to the elite collectors. Indeed ‘traditional music’ (an anachronism when applied to earlier centuries) appears in this light to be a timeless resource for the abstract alliance of Irish Protestant and Catholic throughout history:

It would seem, as was the case with Bunting, Petrie, Goodman and other early Irish music collectors who were Protestant, that the collecting of traditional music and other antiquarian pursuits, aesthetically motivated as they primarily were, enabled Forde to make common cause with his Catholic fellow-countrymen. An interest in the native music was seen as an uncontroversial national bonding agent in the thinking of the United Irishmen in the 1790s, and again as an important element in the forging of non-sectarian national identity by the Young Irelanders in the 1840s. It may also be seen thus implicitly in the activities of John and William Neal in another period of Irish cultural nationalism in the 1720s. (p. xxv, my emphasis)

I will leave aside this dubious conflation of the motives of Dublin music merchants of the 1720s with Victorian antiquarians and ask: What does it mean to say Forde’s motivations were ‘aesthetic’ in nature? In what sense can it be said that he was making ‘common cause’ with Hugh O’Beirne in the autumn of 1846, or with any of the sources of the 900 and more tunes presented in this publication?

The antiquarians described their work as scientific, not aesthetic. To be sure, Petrie wrote some perceptive paragraphs on how peasants sang and played. Nevertheless, he described the collection of music as a branch of archaeology. The peasant singer was to the collector no more than the dirt under his feet. Nor did Forde, who was clearly more aesthetically accomplished than Petrie, appear to have a strong aesthetic interest in the music he was collecting. In a long career as a performer, he appears never to have played any of the music he collected publicly. He only lectured about it, while hatching ambitious and never realised publication plans. Unfortunately, little can be positively reviewed here about the actual science of this scientific enterprise as exhibited in the lecture notes and advertisements, thoroughly polluted as it was by conceptions of ‘national music systems’ and distinctions between civilised and uncivilised musical cultures.

These pioneers of Irish antiquarian science placed supreme value on the musical transcriptions and commentaries they prepared over the specific musical expressions from which they were drawn. Their sole interest was in the ink and paper of the transcription. The corporeal performance, and the performer himself, were objects at best convenient to the task, at worst obstacles in the way of the abstract truths they sought. A number of commentators on nineteenth-century Irish culture have drawn similar conclusions about this dysfunctional relationship, including the present writer:

An ancient, ideal, and pre-Anglicised aristocratic culture was linked and conflated with the most backward locations and practices of peasant culture still surviving, but in a peculiarly ahistorical and abstract way. The actual practitioner is necessarily dehumanised in this relationship. To borrow a Lacanian phrase, the national essence is in the peasant subject more than he is himself in his quotidian actuality. Therefore it was required to distil and abstract that essence from him. (Dowling pp. 236-7, see also Leerssen pp. 197, 225-6)

This provides an insight into what these antiquarians meant when they referred to themselves as ‘Hiberniores Hibernis ipsis’, ‘more Irish than the Irish themselves’. They considered the precious artifacts the peasant held in memory were too delicate and refined for their own illiterate sensibilities (O’Brien Moran, p. 96).

A page from Forde’s first comprehensive manuscript (Royal Irish Academy reference: RIA MS 24 O 26; Image courtesy of the Irish Traditional Music Archive).

Attack on peasant culture

The scientific antiquarian projects were adjacent to and cohered with a full spectrum attack on peasant culture and society taking place in the prefamine decades. The peasantry was made the scapegoat for a dysfunctional property system and dangerously unbalanced economy, sold out by O’Connell and excluded from the political system, their culture under surveillance and attack by landlords, their bailiffs, and their missionaries, if not also by their priests. ‘Common cause’ would be made only with a certain segment of the Catholic population – educated and musically literate, propertied, politically docile, and liable to stock their sitting-room shelves with antiquarian volumes. The exceptional case of Canon James Goodman, the subject of another celebrated ITMA publication, helps prove the point. Goodman’s main source, the piper Thomas Kennedy, was after all a convert, subject to one of the more notable colonial projects of the era: a landlord backed effort to expand the Protestant population on the Dingle peninsula outward from the town and in the Protestant outposts around five lighthouses, a project in which three generations of Goodmans, though often half-heartedly, participated (Whelan, pp. 117, 254–60).

Those who celebrate the ‘scientific spirit’ of the antiquarian music collectors are on safer ground pointing to their obsessive and meticulous fieldwork habits. Petrie was handy enough on the violin to play what he transcribed back to the musician he was transcribing from, in order to secure an accurate transcription. This obsession with the minutia of a tune or song was matched by a penchant for exhaustiveness and the amassing of collections of gigantic proportions, an attitude, in Petrie’s case anyway, inherited from his experience on the Ordnance Survey Memoirs, which, in Leerrsen’s pithy description,

… seems to have taken on Casaubonish proportions. Sixty thousand names of parishes and townlands were surveyed, inch by inch in their full cultural and historical dimension, with a tender-loving care which found no detail too small or too obscure to warrant full and painstaking investigation. The raw material collected by the Historical Department concerning topography, language, history, and antiquities alone amounted to 468 large quarto volumes; a library of Borgesian uncanniness. (Leerssen, p. 104)

The collectors revelled in an intractable problem of their own invention: to find within the haystack of a piper’s massive and wildly eclectic repertoire those items of true authenticity. Petrie complained about Galway piper Paddy Conneely’s repertoire:

Paddy can play not three tunes, but three thousand: in fact we have often wished his skill to be more circumscribed, or his memory less retentive, particularly when, instead of firing away with some lively reel, or still more animated jig, he has pestered us, in spite of our nationality, with a set of quadrilles or galloppe, such as he is called on to play by the ladies and gentlemen at the balls in Galway. (O’Brien Moran, p. 112)

When these were identified, any version or ‘setting’, no matter how trivially different from those already collected and published, was saved. Petrie boasted to the collector Joyce that he had nearly 50 settings of one tune, though this is unverifiable in his manuscripts (O’Brien Moran, p. 101). Not to be outdone by his rivals, Forde claimed in 1844 to have ‘amassed a collection of Irish music larger than that of any previous collector’ (p. xxxiii).

The editors have done little to aid musicians in their navigation of this massive archive of duplication and trivial variation. Regarding the dance tunes, there is no cross referencing to other publications or twentieth-century recordings. By cross referencing titles (aware of the proviso that entirely different tunes can have the same name) to Aloys Fleischmann’s exhaustive assemblage of ‘Irish traditional music’ collected before the famine, the present reviewer can tentatively conclude that as much as a third of The Forde Collection material had already been published by 1850. And like Petrie, Forde saved multiple and trivially differing versions of a significant subset of this previously published material, including airs very well known at the time, and which have survived in the oral culture into the twentieth century (for example ‘Seán Ó Duibhir an Ghleanna’ and ‘Éamonn an Chnoic’ (13 versions each), ‘Róisín Dubh’ (9 versions), ‘An Bínsín Luachra’ (8 versions) and ‘Casadh an tSúgáin’ (6 versions) and about twenty others with at least three versions each).

Carolan suggests that Forde may have had ‘a blind spot for reels’, as only a handful of the 900 tunes could be considered such. This imbalance appears strange in light of the craze for the dance which is much in evidence in the Ordnance Survey Memoirs and the collections of his near-contemporaries Petrie and Goodman (Dowling, pp. 106–8, 121–25). It may be that Forde, as well as some of the collectors who donated manuscripts to him, agreed with Petrie that the ‘old Munster jigs’ played by the pipers were the most valuable and representative. Whatever the case, it appears that Forde was looking to ‘go deep’ in particular musical forms, the better to provide a basis for the analyses he would subsequently make. There are hundreds of piping jigs in 6/8 and 9/8 time, organised in batches in the collection. Some of these batches he imported directly from other collectors, Deasy and Townsend from Cork and MacDowell of Belfast. A small run of jigs (with the few reels he collected) came from James Blair of Armagh, another contact he made in Ballinamore. The largest batch is contained within the grouping of over 100 tunes for which Forde gave no source, and he may have collected these himself from Cork pipers. To play through this material makes for a fascinating (if also mind-numbing) journey, facilitated by the editor’s strategy of transposing Forde’s transcriptions into easily playable keys. The instrumentalist will get a very nuanced feel for the compositional habits of the prefamine pipers, and a sense of how the oldest tunes in the double- and slip-jig repertoire are structured. A picture also emerges of the scope of the repertoire of individual pipers like Paddy Carey of Lag Lane, Cork. No doubt we will see some of these gems surfacing in performance and on commercial recordings in the coming years, as we saw with the Goodman publications a couple of decades ago. (The current reviewer has his eye on a few of these pieces).

The most remarkable example of Forde ‘going deep’ was his encounter with O’Beirne, with whom he seemed to be concerned almost exclusively with the airs to songs. At least 150 of the 182 melodies from O’Beirne were not published previously. By sight reading through them the singer will find close to half of these falling into the typical quatrain patterns of the modern ballad: ABBA, AABA, etc. A dozen of these have titles Forde classified as ‘’98 airs’, and the titles of many others indicate they belong to the massively popular bilingual Jacobite/Jacobin repertoire of the era. There is also an intriguing subset of shorter form melodies that O’Beirne called ‘Kaylinging songs’. But what can be said about Forde’s motivations, his relationship to O’Beirne and to O’Beirne’s art, in light of the fact that he saved not a single line from any of these songs? How is it even possible to treat the performance of a song aesthetically when the words are dispensed with? What evidence is there for making common cause with this prolific performer when the melody is severed from the story as a soul from a body? And is it not too much to ask that the editors, during the course of a project many decades in preparation, might have taken steps to rectify this wrong by investigating what lyrics might be found for any of these songs?

Clearly there is much work to be done now that this long-awaited volume has appeared. If this review has aggressively ‘brushed history against the grain’, this was to remind us that the authenticity in traditional music that continues to haunt us derives less from the notes on the collector’s page than from the courage, humour, fortitude and cunning of the producers of the music, as their tunes and songs come to an end and die in the air, and the forward momentum of progress continues to drag with it the possibility of catastrophe.

Citations and further reading:

Walter Benjamin, Illuminations: Essays and Reflections (Schoken Books, 1969)

Nicholas Carolan & Caitlín Uí Éigeartaigh (eds), The Forde Collection: Irish Traditional Music from the William Forde Manuscripts (ITMA, 2021)

S.J. Connolly, Priests and People in Prefamine Ireland, 1780–1845 (Gill and McMillan, 1982)

James S. Donnelly, Jr. The Great Irish Potato Famine (The History Press, 2013)

James S. Donnelly, Jr. Captain Rock: The Irish Agrarian Rebellion of 1821–24 (University of Wisconsin Press, 2009)

Martin Dowling, Traditional Music and Irish Society: Historical Perspectives (Taylor and Francis, 2014)

Joep Leerssen, Remembrance and Imagination: Patterns in the Historical and Literary Representation of Ireland in the Nineteenth Century (Cork University Press, 1996)

Jimmy O’Brien Moran, ‘Irish folk music collectors of the early nineteenth century: pioneer musicologists’ in Michael Murphy and Jan Smaczny (eds), Music in Nineteenth-Century Ireland (Four Courts Press, 2007)

Irene Whelan, The Bible War in Ireland: The ‘Second Reformation’ and the Polarization of Protestant-Catholic Relations, 1800–1840 (The University of Wisconsin Press, 2005)

The Forde Collection: Irish Traditional Music from the William Forde Manuscripts, edited by Nicholas Carolan and Caitlín Uí Éigeartaigh, is available to purchase from the Irish Traditional Music Archive. Visit www.itma.ie/shop/forde.

Subscribe to our newsletter here.

Published on 3 August 2022

Martin Dowling is a fiddle player and author of 'Traditional Music and Irish Society: Historical Perspectives' (Ashgate, 2014). He lives in Belfast.