What's in an 'S'?

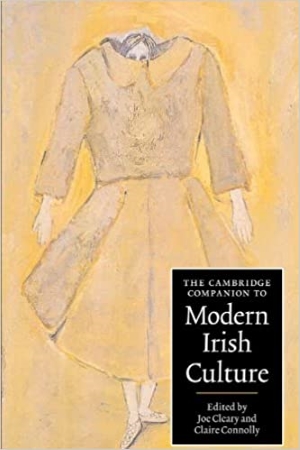

The singularity of the title of Lillis Ó Laoire’s contribution to The Cambridge Companion to Modern Ireland succinctly and pointedly epitomises one of the most challenging aspects of writing about music in Ireland today.1

‘Irish Music’ is understood by many as a shorthand for ‘Irish traditional music’. Certainly, in the vernacular, this is a common assumption to make, and given the huge popularity and presence of traditional music in Ireland and beyond, as well as its invariable alignment with issues of identity and nationhood, one might be forgiven for truncating ‘Irish traditional music’ to ‘Irish music’. But, of course, therein lies the crux.

In a volume of such proposed intellectual weight, to read ‘Irish music’ as essentially ‘Irish traditional music’ is to do a huge injustice to the many musics that have and continue to flourish (or indeed flounder) on this island – not just in terms of what it means to those who make music but also how such musics offer another valuable perspective on what it means to be ‘Irish’. For some, then, this chapter will be remembered for what is absent as much as for what is present here.

Aside from a few brief references, the bulk of Ó Laoire’s representation of ‘Irish Music’ is genre specific (collections of traditional tunes) and era specific (late eighteenth/nineteenth centuries). The responsibility for such a narrow focus is perhaps less the author’s than it is the editors’ for, in the end, the author is writing in his area of expertise and there is no doubt that Ó Laoire is an expert in the field of Irish traditional music, particularly sean-nós singing. Ó Laoire’s remit seems clearly signalled in the preface by the editors:

The country’s traditional airs, sean-nós singing, ballad treasures and folk-music revivals have exerted influence across the globe either in their own right or as stimulus to other musical cultures… in contemporary times Ireland’s accomplishments in popular music especially have won a global audience that will compare in reach with that which its writers have already achieved. (p. xiv)

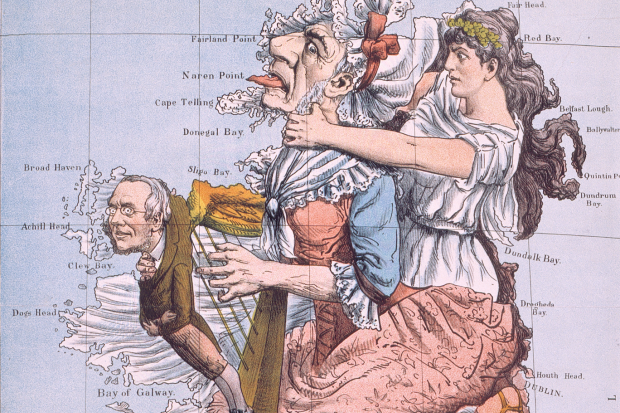

One wonders if in this Cambridge Companion the editors have fallen into the trap of representing music in Ireland in terms of its apparent (outside) success and appeal as opposed to presenting the rich and diverse forms of music practiced on this island in the last two hundred years or more, by honing in on those cultural artefacts and practices that seemingly most separate us from our colonial masters and most mark us as successful and hence truly modern?

If at best a kind of apologia and at worst a clumsy justification for placing Irish traditional music at the ‘centre’ (while in fact it is really the only music focused upon), the editors point out that ‘classical music traditions weigh lightly compared to those of other Western European nationalities’ (p. xiv). The only ‘Irish’ composer in the ‘classical’ vein to be featured at any length is Seán Ó Riada, but even here it is in rather specifically nationalistic terms.[2] This is not the only musical absence to be tacitly sanctioned. Irish country n’ western, arguably Ireland’s true vernacular music, is briefly acknowledged in just one sentence (p. 281). Popular music is treated in a cursory fashion, jazz hardly gets a mention, and the example of a musically heteroglossic island (p. 281) only manages to configure an Irish music world in terms of a traditional core.[3]

To be fair to the author and the spirit of the book, however, it is true that Irish traditional music has been intrinsically linked to, and even configuring of, Ireland’s search for its own brand of modernity, as so cogently outlined in the introductory essay of the volume by Joe Cleary. Ó Laoire delineates his terms of engagement with the topic of Irish music and modernity noting from the outset that ‘this chapter shows how an outline of the changing political climate is crucial for an understanding of the emergence of a canon of “Irish music” as a distinct category’ (p. 267). In this way, Ó Laoire is making it clear that politics and music are powerfully aligned in modern Ireland, a move that invariably and unsurprisingly places the struggle for nationhood at the centre of this discussion and in turn places music in relation to it.[4] However, Ó Laoire never seems to expose the crucial role of historiography in this enterprise and how the writing of a history of Irish music is, in itself, politically influenced and influential. In other words, in this chapter, Ó Laoire reinscribes a history of Irish music that not only places traditional music at the centre but also is unquestioning of that very gesture.

There are some tantalising moments of potential rupture to the metanarrative, such as the discussion of Francis O’Neill’s collections of music, particularly The Dance Music of Ireland (1907).[5] Ó Laoire points out that O’Neill sometimes included material in his collections that did not fit a prescriptive model of what it meant to be ‘Irish’ (p. 277). However, this crucial point is not explained or developed on any level. In fact, the centrality of the notion of ‘authenticity’ in the discourse on Irish traditional music is never critiqued or engaged with as a means of reflecting back onto the tradition in order to uncover and examine objectively its central concerns and how the traditional community imagines itself (particularly in terms of its relationship to the nation-state).

Comments on the ‘reappraisal’ of Edward Bunting’s suspect editorial methods by Breathnach and others underscore this imagining. By putting the transcribed music of the harpers into a ‘major and minor system of keys’, Ó Laoire notes, Bunting’s work now needs to be ‘approached with caution’ (p. 269). It is crucial to note that Breathnach himself asserted that Bunting ‘had no licence to tamper with the music’,[6] which essentially denies Bunting the right to (re)present the music on the grounds of inauthenticity, but, if anything, Bunting and others need to be revisited in light of different versions of modernity and different histories of ‘Irish music’ that are imminent in these texts.[7]

In a similar vein, Ó Riada’s ‘orientalizing imagining of Irish music’ did far more than interest those that had previously rejected this music, though this was certainly part of Ó Riada’s agenda. In Our Musical Heritage, Ó Riada maintained that Irish music was not only not European but ‘quite remote from it’ being ‘closer to some forms of Oriental music’.[8] This move is crucial in establishing a discourse that not only ‘authenticates’ but also very much ‘others’ Irish music by aligning it with musical cultures of the ‘mystical’ East and, more specifically, with post-colonial nations such as India (p. 279).

Thus, the implication of modernisation as being ‘coterminus with anglicization’ (Cleary, p. 3) is not articulated directly, but the very structure of the chapter reveals this reading. As a result, for Ó Laoire, early modernity is less problematic, hence the focus on key music collections of the nineteenth century (underscored by the fact that clearly this is an area he knows intimately and on which he writes very well). Arguably, the most compelling musical articulations and representations of Irish modernity are to be found in radio and television, not to mention in education, which receives very little attention here, being reduced to one brief paragraph at the end of a chapter that telescopes very rapidly.

In light of the stated aim of the Companion, which is ‘to introduce readers to modern Irish culture in all its complexity and variety’ (p. 1), this remit has been only partially fulfilled in an undoubtedly detailed but nonetheless limited way. What we have in this chapter is, in the first instance, a focus on just one music to the exclusion of others, and, arguably more seriously, a somewhat (though not always) uncritical acceptance of the categories of understanding that inform definitions of ‘Irish music’.

But then writing a chapter on ‘Irish Music’ as opposed to ‘Musics in Ireland’ for such a volume was always going to be a difficult, even thankless, task. There is no denying that Ó Laoire is an engaging and informed writer, but the problems of categorisation and definition he has been forced to tackle (or rather avoid) here are perhaps too great for such a brief chapter. Yet, ironically or not, this chapter does go some way in representing the state of ‘Irish music’, both as a conceptual category and as a reality today, by contributing to a debate that is contentious, searching, active, and promising.

It is clear that Irish traditional music has, for a long time, had to bear a greater portion of the semiotic load for the nation. Perhaps it is time, once again, to rethink the terms of this position and to pluralise not just ‘Irish music’, but also ‘Irish identity’.

Ó Laoire, Lillis. ‘Irish music’ in The Cambridge Companion to Modern Irish Culture, Joe Cleary & Claire Connolly (eds), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

See reply from Joe Cleary here.

Published on 1 July 2005

Aileen Dillane is an ethnomusicologist and musician based in the Irish World Academy, University of Limerick.