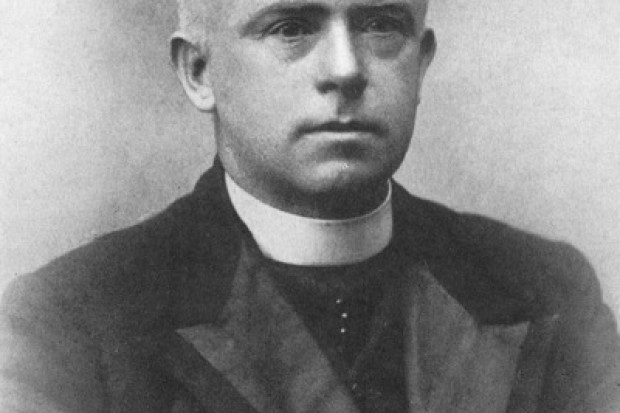

Chief Francis O'Neill

The Collector as Coloniser?

Much has been written about the man who influenced the development of Irish traditional dance music in the twentieth century. From Nicholas Carolan’s A Harvest Saved: Francis O’Neill and Irish Music in Chicago (1997) to Chief O’Neill’s Sketchy Recollections of an Eventful Life in Chicago (2008), edited by O’Neill’s great-granddaughter Mary Lesch and Ellen Skerrett, Francis O’Neill remains a consistent source of fascination for musicians and scholars. There have also been numerous journal articles, essays in edited collections and references in doctoral theses that explore music making in Irish emigrant communities in Chicago and its environs, and, most recently, two other new books: Richie Piggott’s Cry of a People Gone: Irish Musicians in Chicago 1920–2020 and Seamus Kelly and Aileen Saunders’ A Biography of Chicago Patrolman John Ennis and his Piper Son Tom, 1847–1941.

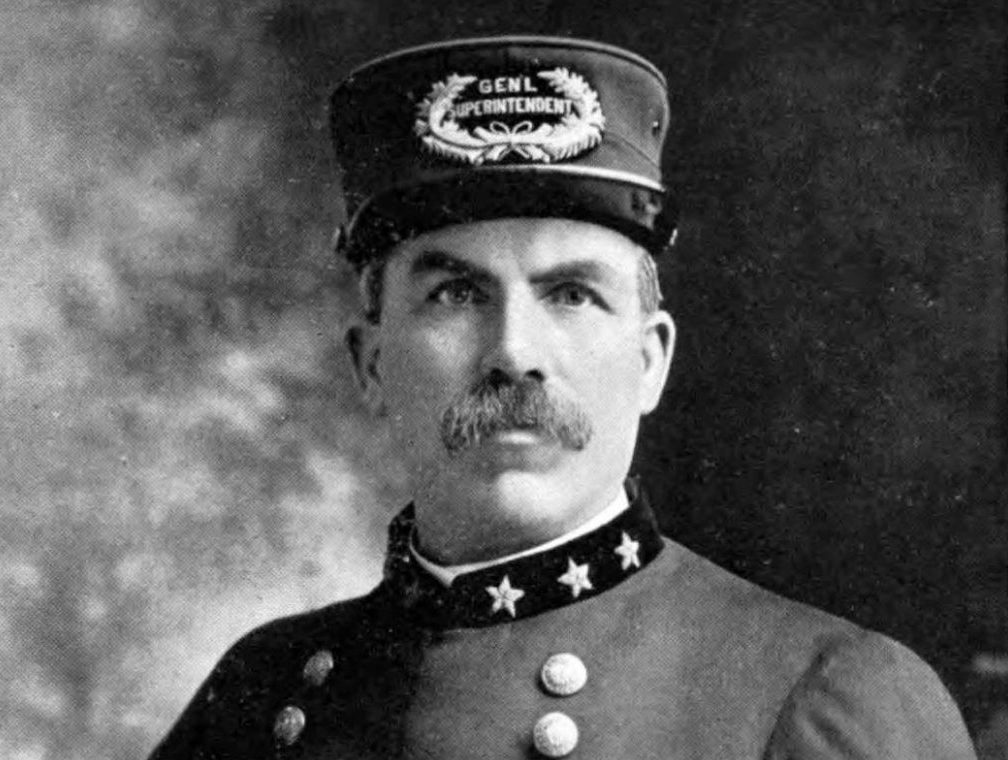

Aside from his lifelong passion for Irish traditional music and his labours as a collector, O’Neill lived an extraordinary life. Born to a relatively prosperous farming family in Tralibane, County Cork, in 1848, he left the family home in 1865 to embark on an adventure which brought him around the world. He worked as an apprentice seaman and, later, assistant steward on several ships, including the Minnehaha, which was wrecked on Baker’s Island in the Pacific Ocean; he was on the verge of starvation when a passing ship rescued him and brought him to Honolulu, from where he made his way to San Francisco. He worked as a shepherd in the Sierra foothills, taught mathematics at a school in Missouri, worked as an unskilled labourer at a meatpacking house in Chicago, joined the Chicago Police Department in 1873, was shot in the first month on duty, and rose through the ranks to become Chief of Police. O’Neill, known as ‘the Chief’, served on the force during the Gilded Age, a period of rapid economic growth marked by significant advances in technology and industry but also by civil unrest, frequent strikes and political scandals. While O’Neill enjoyed much success in his professional life, his personal life was tinged with tragedy as he and his wife Anna endured the loss of six of their ten children.

O’Neill was meticulous about creating and curating his legacy in the final decades of his life but, as Michael O’Malley notes in his new book, some of his accounts do not ‘match the historical record very well.’ O’Neill’s Irish Folk Music: A Fascinating Hobby (1910), Irish Minstrels and Musicians (1913) and Chief O’Neill’s Sketchy Recollections of an Eventful Life in Chicago (2008) are frequently referenced by O’Malley. He also draws on and condenses the considerable literature on O’Neill and the rich cultural heritage and sociopolitical life in Chicago in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to supplement some of the sketchier details and to correct errors that he attributes to O’Neill writing his memoirs in old age. Some material included in the book and additional images, information on the structure of Irish traditional music, and musical examples are included on a supplemental website, www.thebeatcop.com – this is an excellent educational resource and an innovative way for the author to promote his extensive research.

From Tralibane to Chicago

The introduction to The Beat Cop sets out O’Malley’s basic premise that, for O’Neill, police work and the collection of music ‘were flip sides of the same coin, part of new ways of thinking about community, part of the administrative and management techniques of modern industrial society.’ O’Neill ‘used techniques of the modern police force to map and colonize Irish music’, and the process enabled him ‘to make sense of himself as both Irish and American’ and to produce collections ‘that established the transatlantic relationship of Irish music and Irish people’. After this short introduction, seven chapters explore O’Neill’s life and multiple careers chronologically.

The first chapter focuses on O’Neill’s privileged upbringing and education as part of a family of strong farmers; the following chapter looks at O’Neill’s life at sea and his encounters with other races and cultures. Chapter 3 charts the challenges that Francis and Anna O’Neill faced in the early years of their marriage and the broader issue of the exploitation and vulnerability of Irish immigrants in the US in the 1860s/70s. Set against the seedy reality of Chicago in the late nineteenth century, chapter 4 chronicles O’Neill’s career as a policeman and his rise through the ranks through hard work, intelligence, ability and meticulous record keeping, as opposed to relying on the corrupt system of cronyism. Chapter 5 explores a range of fascinating themes, including the influence of the Celtic Revival and the de-anglicisation policies of Douglas Hyde on O’Neill and the participation of Irish immigrants in societies and movements that allowed them to connect with political and cultural issues in Ireland. O’Neill’s final years in office and his retirement are the focus of chapters 6 and 7; they include an account of his attempts to reform the police force and his efforts (ably assisted by James O’Neill and others) to collect, analyse, and publish thousands of Irish tunes. (Caoimhín Mac Aoidh has written in detail about the life and career of James O’Neill and his close working relationship with Francis O’Neill.)

It is impossible to summarise The Beat Cop in a short paragraph, but it is worthwhile, as it conveys the breadth and depth of research undertaken by the author. O’Malley is an historian with an impressive range of research interests. He has written on various topics over the last three decades, including the invention of standard time and the adoption of daylight saving (Keeping Watch: A History of American Time), and histories of technology and money in the United States (Face Value: The Entwined Histories of Money and Race in America). In The Beat Cop, O’Malley skilfully illustrates how information on topics as diverse as the Bertillon system (that catalogued criminals based on their physical measurements) and the origin and economic significance of the Emigrant Savings Bank can provide a richer perspective on contemporary life and animate a character and historical period. Considering the author’s impeccable and extensive research (reflected in the information-packed endnotes), it was surprising to read several unsubstantiated statements woven through the text; these were part of a subtheme that runs through the book, namely, the interrelation of colonialism with Francis O’Neill’s life and work.

From colonial boy to coloniser of Irish music

O’Malley asserts that British colonialism shaped O’Neill’s life from early childhood. He notes that the O’Neill family were complicit with the colonial system and used it to claw ‘out a relatively favorable position’ probably by evicting subtenants from their land or gaining the right to lease land made available by death or emigration. O’Malley believes that this early exposure to the structures and practices of colonialism influenced every aspect of O’Neill’s life and career. The author extends this narrative to O’Neill’s music collections, which he views as ‘a kind of colonial project, extracting resources from the city he administered.’

The implication that O’Neill was a colonial actor who used the manipulative tactics of a colonial administrator to exploit Irish traditional musicians and acquire their tunes is intriguing, but unconvincing. There are too many questions left unanswered by O’Malley. How exactly did O’Neill exploit musicians? What penalties did he apply to those who did not part with their tunes? Why was O’Neill honourable and fair in his police work, and manipulative and vindictive in collecting music?

Prominent figures often attract criticism, and O’Neill has attracted his fair share over the years. His failure to adequately acknowledge both his indebtedness to various collaborators and informants and his reliance on collections by William Forde, William Bradbury Ryan and others for source material has drawn much criticism (see Paul de Grae’s essay in Ancestral Imprints: Histories of Irish Traditional Music and Dance or Michael D. Nicholsen’s in Crafting Infinity: Reworking Elements in Irish Culture, both 2012). To date, this criticism has focused mainly on his modus operandi; O’Malley’s book shines a spotlight on the character and lineage of O’Neill, and the result is overwhelmingly negative. He is described as an ‘outsider’ or ‘observer’ who is guarded, socially awkward, controlling, obsessive, and bothered by disorganisation; he has ‘a glaring lack of empathy or compassion’, and the author speculates that O’Neill would be classified nowadays as ‘on the spectrum’ of autism. It must be stated that this is pure conjecture, but it raises the question: why did the author choose to cast O’Neill as the villainous colonial actor?

O’Malley’s characterisation of O’Neill appears to be part of a narrative occasionally applied to collectors of Irish traditional music, mainly in the nineteenth century, that demonises them and often discredits their collections. A recent review by Martin Dowling of an edition of William Forde’s manuscripts in this journal articulated the view that Forde and contemporary collectors, such as George Petrie, were solely interested in transcribing the music and not in the performers/informants who were described as ‘objects at best convenient to the task’ or, in the case of the ‘peasant singer’, as ‘no more than the dirt under [the collector’s] feet’. Collectors are motivated to expend years of their lives collecting music for various reasons; passion for the music is paramount, but patriotism and a fear of the imminent disappearance of the music are often influential factors. Undoubtedly, vanity plays a part for some collectors as these projects and publications guaranteed a place in the history of Irish traditional music, or, as the collector Edward Bunting wrote after the publication of Ancient Music of Ireland (1840) – ‘a page in the history of man’ (see Charlotte Milligan Fox’s Annals of the Irish Harpers, p. 305). It is easy to demonise collectors, to dismiss their legacy or to view their interactions with their informants through a critical and morally superior twenty-first-century lens; but what does this achieve? Similarly, perpetuating a myth that collectors were messianic figures that single-handedly saved Irish traditional music is pointless. A fruitful interrogation of the collectors requires an approach that is neither character assassination nor canonisation.

There is always merit in reassessing the life and legacy of prominent historical figures, and a postcolonial-inspired historiography such as The Beat Cop certainly challenges the reader to look at O’Neill’s life and work in a different way. Although this book is a welcome addition to the literature on the culture, history and music of the diaspora in Chicago in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, it does not provide a richer, more nuanced understanding of Francis O’Neill. The Beat Cop could, however, inadvertently serve as a catalyst for a long overdue discussion on complex yet pertinent issues relevant to collectors (particularly from the nineteenth century), their methods of collecting, ownership of material, and the effects of social and cultural power relations between collectors and informants. An exploration of these subjects could deepen our understanding of Irish traditional music in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and inform contemporary collecting practices in the twenty-first century.

The Beat Cop – Chicago’s Chief O’Neill and the Creation of Irish Music by Michael O’Malley is published by The University of Chicago Press. Visit https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/B/bo143122232.html.

Subscribe to our newsletter.

Published on 6 December 2022

Mary Louise O’Donnell is a Fulbright Scholar, musician, and cultural historian.