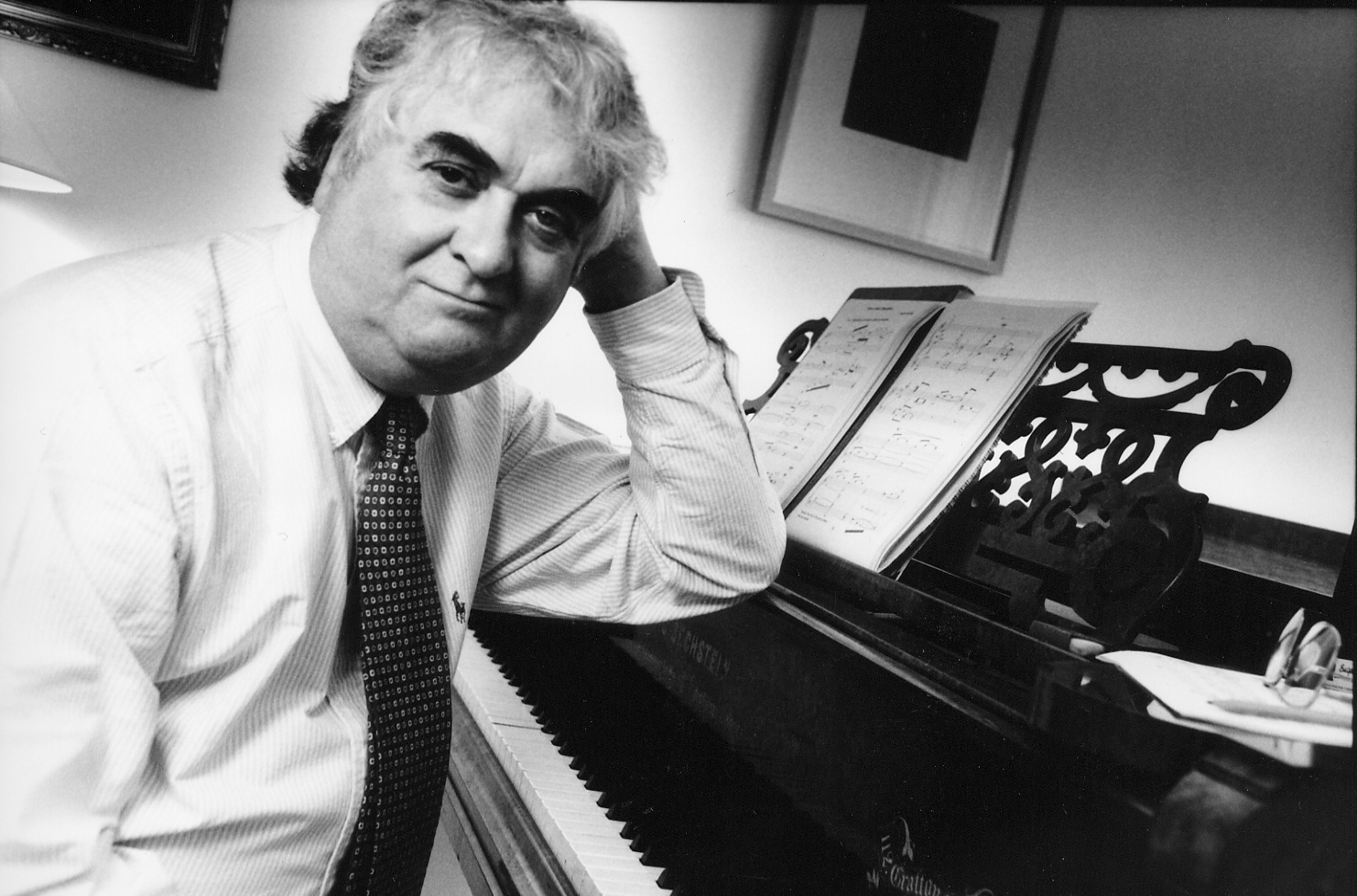

Seóirse Bodley (Photo: Contemporary Music Centre)

Seóirse Bodley at 90

This April marks the 90th birthday of Seóirse Bodley, one of the most significant Irish composers of his generation. In 2008 he was the first composer in Aosdána to be elected to the title of Saoi, a prestigious honour bestowed on those whose work has been exceptional in its quality and sustained output. He has also made telling contributions to Irish musical life as a university teacher, scholar, organiser, broadcaster and performer. A number of events are marking the occasion, including performances at the New Music Dublin festival this week of his orchestral work A Small White Cloud Drifts Over Ireland (Friday, 7.30pm), and the Earlsfort Suite for soprano and piano (Saturday, 3pm).

Bodley’s early musical life was rich: a piano student at the Royal Irish Academy of Music, he contributed to solo and chamber music concerts, and had already begun to study composition before beginning his music degree at UCD. There, as Gareth Cox describes it in his 2010 biography of the composer, ‘he threw himself enthusiastically into student life’. It was also at UCD that he got the opportunity to write arrangements of Irish traditional music and songs for Raidió Éireann’s small orchestra. (One later arrangement, that of ‘The Palatine’s Daughter’, became familiar through its use as the theme tune for RTÉ’s television drama The Riordans). Thus began one of the key themes of Bodley’s output: to somewhat over-simplify, it addressed the question of how to create new music that could satisfactorily accommodate the principles of Irish traditional music and contemporary music, without necessarily synthesising or fully combining the two.

This was not a new concern; for instance, Annie Patterson imagined in 1909 that the study of folk music would lead to an Irish school of composition, and Aloys Fleischmann in 1935 called for ‘a Gaelic art-music which will embody all the technique that contemporary music can boast and at the same time will be rooted in the folk-music spirit’ (‘The Outlook for Music in Ireland’). As Cox notes, Bodley’s own teacher, John F. Larchet, espoused similar views on the nature of Irish composition.

In actuality, Bodley’s trajectory as a composer was originally more informed by European models, initially through his studies with the Austrian composer Johann Nepomuk David, and more critically through his encounters with modernism, following visits to the Internationale Ferienkurse für Neue Musik Darmstadt in the early 1960s. As Mark Fitzgerald notes in a 2018 article, Bodley was one of the first Irish composers to really grapple with serial composition, in particular adapting later forms of integral (or total) serialism, where series are applied not just to pitch, but also to other aspects of the musical material. Other avant-garde techniques became part of his musical language at this time; the orchestral work Configurations (1967) included an expanded and spatially arranged orchestra divided into two sections, aleatoric passages, and the use of stopwatches for section leaders. Other important works in this mode were his first string quartet and a chamber symphony.

His first major vocal works belong to this period, and, as Lorraine Byrne Bodley argues in A Hazardous Melody of Being: Seóirse Bodley’s Song Cycles on the Poems of Michael O’Siadhail (2008), song ‘unequivocally occupies a central position and has important significance in other areas of Bodley’s creativity’. His devotion to a quintessentially European form (which had been underdeveloped in Ireland) is striking, with song cycles (both orchestral and for voice and piano) written on the poetry of such diverse artists as W.B. Yeats, Brendan Kennelly, Antonio González-Guerrero, Goethe, Seamus Heaney, and O’Siadhail.

Unlikely source

Although Bodley had rapidly and successfully assimilated and integrated avant-garde processes into his compositional language, the relative predictability produced by these were problematic. The solution to this came from a familiar yet perhaps unlikely source: traditional music and song. While Bodley had long been committed to the Irish language (writing articles for Comhar), music and literary culture, this new direction seems likely to have been also prompted by the broader folk and traditional music revival. He was one of the founders of The Folk Music Society of Ireland (Cumann Cheol Tíre Éireann) in 1971, and was its first chair, serving for much of the society’s existence. Established at a time when the revival was beginning to flourish, the society aspired to foster an equal vigour in the research and scholarship of traditional music. Bodley was co-editor with Hugh Shields and Breandán Breathnach of the society’s journal, Éigse Ceol Tíre, and contributed a study of sean-nós singing to its first issue. He also transcribed and annotated carols from Jack Devereux for Diarmaid Ó Muirithe’s edition of The Wexford Carols, which documented a living repertoire and tradition of singing that extended back to the seventeenth century.

Signalling this influence of traditional music on his compositional style was the pivotal work The Narrow Road to the Deep North (1972), written for two pianos (with a later solo piano version). The piece begins with a melody in sean-nós style, which is juxtaposed with dissonant, atonal musical elements, which are later set against each other. Bodley’s aim was not necessarily to synthesise these musical worlds, but to explore what Axel Klein, in his New Grove article on the composer, terms the ‘creative conflict’ between them. It was a striking departure, drawing directly on his study of sean-nós song, and formed the basis for a sustained exploration of how traditional music could be integrated into his compositional voice.

Perhaps the best-known work of this period is the orchestral piece A Small White Cloud Drifts Over Ireland, described by Bodley as combining fragments of newly composed jigs, reels and airs with highly contrasted musical materials (clusters, atonal writing and more tonal sections). It demonstrates his depth of knowledge of the tradition by not relying on quotations of pre-existing material, but by being able to write in a convincing ‘traditional’ style (and also notate these in a way that aimed to reproduce as much as possible the rhythmic swing of the music). Other large orchestral works of this period continued this approach. His second symphony, subtitled ‘I Have Loved the Lands of Ireland’ (1980), commemorated the centenary of Pádraig Pearse, and was in the words of Bodley ‘a post-modern Irish symphony’, attempting to ‘delineate the essence of the emotional and psychological history of the Irish people’ (Irish Musical Studies 7, p. 137). The fifth – The Limerick Symphony (1991) – continued this exploration of Irish identity through symphonic means, although the references to traditional music are much less prominent.

Bodley’s engagement with traditional melodic contours also found its way into his sacred music, and in particular his congregational mass settings. The Mass of Peace (1976) probably contains his most-performed and best-known music; John O’Keeffe comments in The Masses of Seán and Peadar Ó Riada: Explorations in Vernacular Chant (2017) that its popularity and effectiveness stems from Bodley’s ‘ingenious re-use of complete motifs and motivic fragments’ from the Gloria to create a unified and memorable composition.

Critical reception

The reception to this period of Bodley’s music has sometimes been polarised, with some dissenting voices echoing the earlier stance of Denis Donoghue in 1955, who cautioned against ‘the trap of folk music’ (‘The Future of Irish Music’); for such commentators, the use of Irish traditional musical material within a contemporary music framework, and alongside modernistic techniques, was inherently problematic. Others considered this music as a retreat from the modernism of his 1960s compositions, with Mark Fitzgerald describing him as adopting ‘a neo-romantic tonal language inflected with Irish traditional music’.

Axel Klein takes a much more measured and positive view, arguing that his has been the ‘most coherent and challenging use of traditional music in a modern context’ (Irish Musical Studies 7, p. 178). His key argument is that Bodley was not relapsing into the mere quotation of Irish melody, in the sense of trying to shoehorn traditional tunes into contemporary music forms, but instead ‘openly confronted the different musical materials’. Perhaps, as he suggests, the challenging nature of this encounter was what resulted in its dismissal.

Bodley himself was keenly aware of the potential pitfalls of such an approach to composition. In a 1958 interview he stated that ‘The greatest danger which faces the Irish composer is that of false nationalism. In other words, he must not write music in an Irish style out of a sense of duty’. He returned to the issue in a 1973 interview, which recognised the complexities underpinning the personal nature of such an approach: ‘It’s rather easy I feel to say that Irish composers must write in a sort of national idiom and that’s that, but there’s a whole range of social, emotional and psychological aspects of the matter that impinge on the whole type of work you’re doing. Often artists don’t quite know what’s motivating them to do anything. I don’t always know myself’.

A different type of engagement with Ireland is evident in the later song cycles The Naked Flame (1987) and The Earlsfort Suite (1999–2000); Byrne Bodley comments on how these reflect on contemporary Irish life, Dublin (and its architecture), the predicament of identity in an urban context, and indeed on the form of modern art song itself. By this stage, Bodley’s writing had begun to re-engage with the modernist musical techniques he had cultivated in the 1960s, and adopted a more atonal idiom, albeit with more freedom. Several virtuoso piano works heralded this new direction: News from Donabate (1999), Chiaroscuro (1999) and An Exchange of Letters (2002) are substantial pieces that would benefit (as would a number of his other works) from being more widely performed and recorded. Further substantial later works include the third and fourth string quartets (2004, 2007) and a series of works setting texts by Goethe. His commitment to song was also evident in a further cycle for soprano and piano using Seamus Heaney’s texts, The Hiding Places of Love (2011).

From the perspective of the present, where the boundaries of genre have become more eroded, and where different musical traditions are regularly brought together (both by composers notionally situated within the contemporary music world and by traditional composers and musicians), we might begin to recognise Bodley as a crucial figure in laying the groundwork for this activity. His engagement with traditional music, regarded by Klein as ‘a unique achievement… not sufficiently appreciated today’ (Irish Musical Studies 7, p. 178), undoubtedly contributed to the current state of music in Ireland, where the interfacing between traditional and contemporary music has become commonplace. As a composer, he has continuously sought out new directions, and his embracing of modernism in the 1960s was of crucial importance in the development of an avant-garde Irish music. Throughout his work, his compositional voice has embraced a plurality of musical styles, and yet retains a distinctive character, honed through a lifelong dedication to the art and craft of the composer.

A Small White Cloud Drifts Over Ireland (1975) by Seóirse Bodley will be performed by the National Symphony Orchestra at the National Concert Hall on Friday 21 April at 7.30pm, along with world premieres by Amanda Feery and Ann Cleare. To book tickets, see here. Earlsfort Suite for soprano and piano (1999–2000) will be performed by the Evlana ensemble at 3pm on Saturday 22 April in The Studio at the NCH, along with a world premiere by Jenn Kirby and music by Missy Mazzoli, Fergus Johnston, George Crumb and more. To book tickets, see here. For full details on New Music Dublin, visit www.newmusicdublin.ie.

Subscribe to our newsletter.

Published on 18 April 2023

Adrian Scahill is a lecturer in traditional music at Maynooth University.