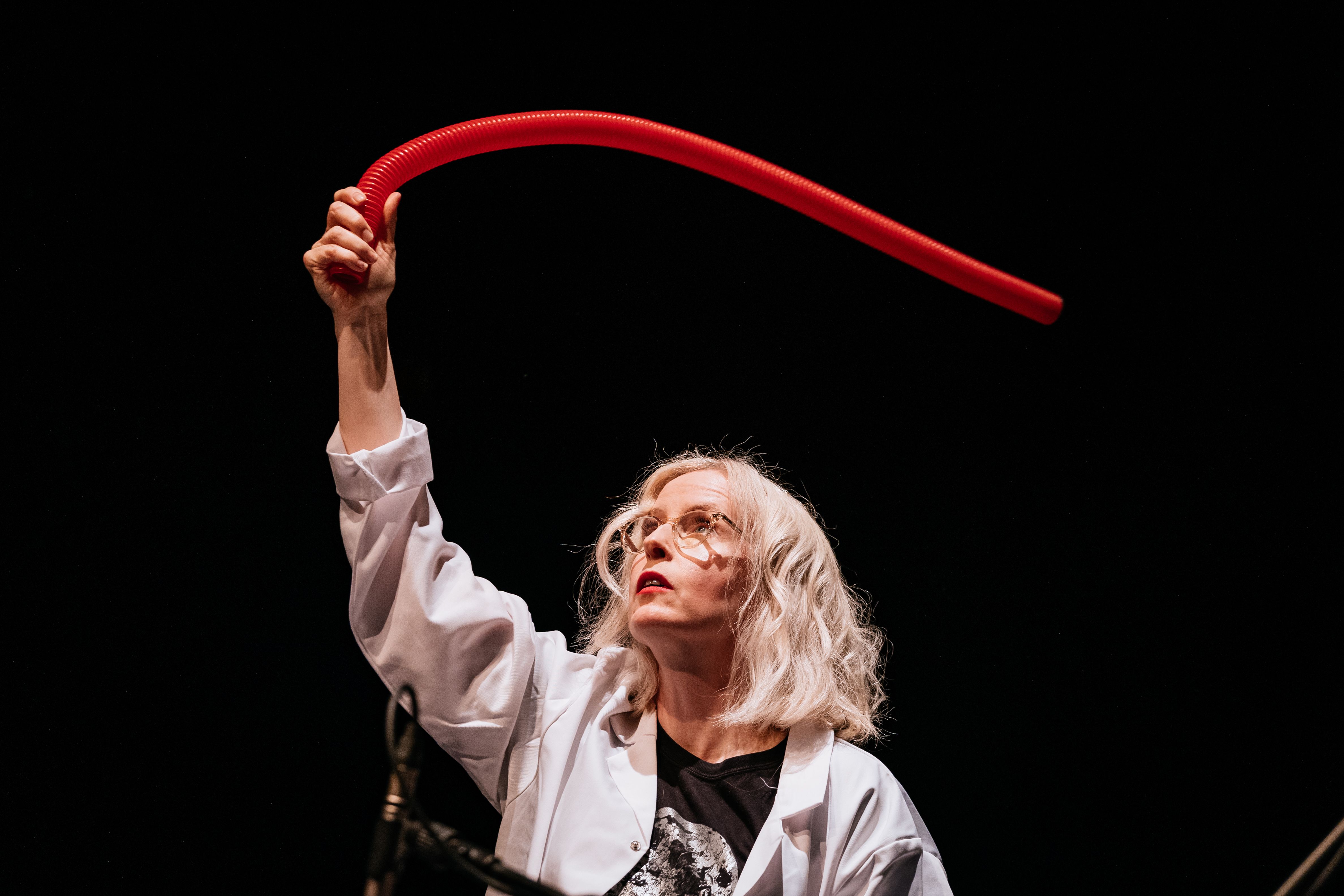

Jennifer Walshe in 'Oscailt' (Photo: Simon Lazewski)

Walshe's World of Dislocation

You do have to hand it to Jennifer Walshe: there are few other composers who so thoroughly explore what it means to live through our hyper-stimulated, digitally saturated world and manage to keep apace with the latest trends and absurdities that regularly flash across our screens. Her new work Oscailt, commissioned by Music Network, focused on artificial intelligence (AI) and the simultaneous feelings of awe and fear that this technology tends to inspire in us. Typically for a Walshe production, this exploration intersected with several other narratives such as Ireland’s position as a global tech hub, the inanities of social media, global capitalism and several other themes that together reflect the multi-dimensional nature of contemporary existence.

The stage in the Samuel Beckett Theatre was set up like a mad scientist’s lab with four tables containing an array of instruments – musical, scientific and electronic – positioned across the stage. The four main performers – Jennifer Walshe (vocals, electronics), Elizabeth Hilliard (soprano), Nick Roth (saxophone) and Panos Ghikas (viola/electronics) – wore white lab coats for the duration of the performance. Above the stage, a large screen projected various AI-generated images according to the focus of the different sections.

After a brief piece of audience participation that involved generating material for a sampler, the work began proper with an investigation of the electromagnetic field (EMF) around us. Student performers from Loretto College in Dalkey were tasked with picking up signals from electronic devices using Ether microphones, whose inputs were made audible via a Bluetooth speaker. These blended with a drone intoned by Roth on saxophone as Walshe read out an explanatory text about the pervasiveness of EMF in our environment before launching into her trademark pseudo-mystical style of singing.

Nick Roth (Photo: Simon Lazewski)

Ancient Internet

This neatly segued into the next section whose focus was the ‘Irish Prehistoric Internet’ – the lighting of bonfires on mountains and other elevated vantage points across ancient Ireland to send messages. This was compared with the modern practice of placing phone masts and other communication technology on hilltops. While a text explaining all of this was read out by Hilliard and Roth, a drone-based halo texture formed a backdrop to surface doodlings of ringtones and internet dial-up sounds that increasingly cluttered the sonic space.

The thread linking the modern Ireland of data centres and global technology firms with its historical legacy as a place of scientific enquiry was one of the work’s strongest points. In later sections, the audience learnt about the Leviathan telescope – the largest telescope in the world at that time – that was built by William Parsons, the 3rd Earl of Rosse, in Birr in 1845, and the first transatlantic telegraph cable between Europe and North America which came ashore at Foilhummerum Bay at Valentia Island. Just at the point where one began to wonder why Fáilte Ireland had not already seized on this marketing theme to attract American tourists, Walshe underlines the Janus-faced nature of technological progress. Parson’s discoveries of distant galaxies with his telescope occurred side-by-side with the terrible suffering of the Great Famine, while Ireland’s current data centre boom gobbles up 18% of the country’s electricity in the middle of a climate crisis.

In getting all of this information across, the performers used lengthy passages of spoken text throughout the piece that was admittedly tedious at times. A section on the Giant’s Causeway, for example, was first narrated by Hilliard, who recounted its formation and mythical significance. It was then followed by a digression on AI’s capacity to reproduce images of the Giant’s Causeway that included everything from an alien invasion to a cat rave. As amusing as this was, the section was capped off with a warning about AI’s potential for replicating inherent biases by projecting several images that had responded to a request to recreate a family photo at the landmark. The absence of any people of colour or same-sex couples in the resulting images was noted by Walshe who declared that ‘it’s the responsibility of everybody to make sure that AI is fair’. Often, in some of her pieces, the direct spoken statement of a particular message can have the impact of a sledgehammer when the timing is right. Here, however, the sermon dragged on to the extent that it began to resemble a spoken-word setting of an opinion column. It is not that Walshe is incorrect. It is just that it is aesthetically unsatisfying to receive this message in such bald terms.

Jennifer Walshe, Panos Ghikas and Nick Roth (Photo: Simon Lazewski)

Teenagers eclipsed

The piece tended to be more effective when a more oblique approach was taken. The most powerful moment came in the final section of the piece when two chords oscillated back and forth while Walshe and Hilliard quasi-improvised a haunting duet on the words ‘Something that is Continuous’. The ethereal music accompanied a striking AI-generated image of a teenage girl staring into a tablet surrounded by lush nature. As the improvisations became more intense, the image zoomed out revealing hundreds of teenagers with smartphones and a fantastical looking landscape that reduced the initial girl to a tiny pixel who was eventually eclipsed altogether. There was much implied here about the potential of technology to subsume the individual into an artificial universe of distraction where unseen powers end up determining one’s fate.

While some sections were more convincing than others, the piece was another example of the sheer multitude of levels on which Walshe works. Beyond the show’s thematic content, the music itself ran the gamut of everything from chant, Irish traditional and free improvisation to electronica and drone-based ambient sounds – at one stage even a spatially separated children’s choir appeared from the back of the theatre. In short, dislocation was a guiding principle of the show, and I imagine that few audience members would have come away from the show without having been forced to reflect on the direction in which our world is heading.

Oscailt by Jennifer Walshe is currently on tour and can be seen at the Belltable in Limerick tonight (21 September) at 8pm, then Triskel Arts Centre in Cork on Saturday 23rd, and the Linenhall Arts Centre in Mayo on Tuesday 26th. For booking, visit www.musicnetwork.ie/whats-on/jennifer-walshe.

Published on 21 September 2023

Adrian Smith is Lecturer in Musicology at TU Dublin Conservatoire.