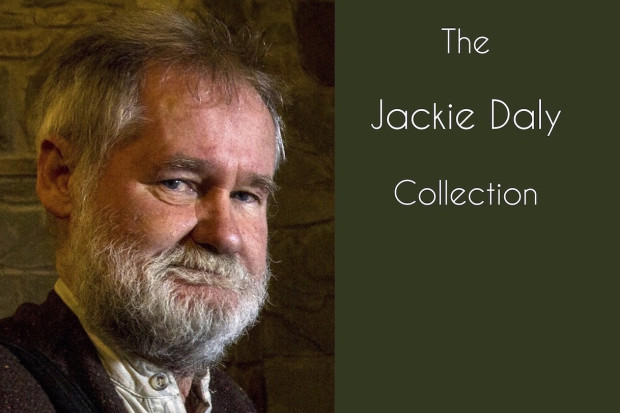

Micheál Ó Domhnaill

Micheál Ó Domhnaill (1951–2006)

Like many Irish speakers living in the urban Gaeltacht of Belfast, I have many happy memories of that unique rite of passage that was the teenage sojourn at summer college in the Donegal Gaeltacht. The first year, I went to Mín a Chladaigh and the second year I spent six weeks in fabled Rann na Feirste.

During my stay there, parts of my native city, including part of the street where I lived, were being razed to the ground in the sectarian upheaval that convulsed Belfast in 1969. People were being murdered and hundreds of families fled their homes as we watched in horror on little black-and-white televisions beside the turf fires, the same televisions on which we watched Neil Armstrong land on the moon a month before.

The house of Mhicí Sheáin Néill in Rann na Feirste was a sanctuary to me and to the likes of me, but there was another reason why the trip to Rann na Feirste and that period was so unforgettable. One day, while hanging around Choláiste Bhríde in that sweltering summer of 1969, two young men, a little older than ourselves, appeared and started singing and playing guitars. This wasn’t what we were expecting. These were Beatles songs and pop songs of the period sung with hand-in-glove harmonies accompanied by mellifluous guitar. It cast a spell on us. The two young men were Daithí Sproule and, God rest him, Micheál Ó Domhnaill who died in July.

Later, the two had a much bigger audience than the raggle-taggle students of Coláiste Bhríde, when they formed Skara Brae with Mícheál’s sisters Tríona and Maighread Ní Dhomhnaill. If there is such a thing as ‘the soundtrack of your life’ the eponymous Skara Brae album, their one and only recording together, filled that role for me and many like me back then. It had to do with mórtas cine, pride in who you are. ‘This is us, this is our music, this is our culture, isn’t it brill?’ was the subliminal message that came out of the record player, especially for those of us from across the border. It was a mainstay at a time of uncertainty.

The music of Skara Brae was part of the definition of who we were on an intellectual level, but on another level, it was creative, sprightly and fun. It was great craic before the word craic was invented. We fell in love with the harmonies on ‘Bán Chnoic Éireann Óighe’; there was rarely a sing-along that didn’t feature ‘An Cailín Rua’; we became sad when we listened to ‘Tá Mé ‘mo Shuí’; we could never work out the lyrics of ‘An Suantraí’.

Micheál and the others learned much of their repertoire from their aunt Neillí Ní Dhomhnaill and of course their father, Húdaí, was a store of song and story. From those familial bonds, Mícheál and the others forged a musical link between the communities in which these folk songs lived and breathed and the current and future generations who will come to value the cultural richness that is found in the Irish language. Unfortunately, Skara Brae lasted only a short while, but their impact was greater than their short lifespan. It wasn’t long, however, until Micheál and Tríona ended up in another band, Seachtar, or as they later became better known, the Bothy Band.

‘Irish music’s unrivalled exemplars’, was how the Rough Guide to Irish Music described The Bothy Band which, as Seachtar, originally included Tony MacMahon, Paddy Glackin, Matt Molloy, Paddy Keenan and Donal Lunny as founding members as well as Micheál and Tríona. Again, The Bothy Band only lasted a few years – according to Kevin Burke, who subsequently played fiddle with the band, they had broken up before people suddenly realised what they were all about.

What many people forget is that Micheál was also the first presenter of the famous music programme on RTÉ radio, The Long Note, between 1973-1974. He was to present another radio series, Cuideachta an Cheoil on Raidió na Gaeltachta, before his untimely death.

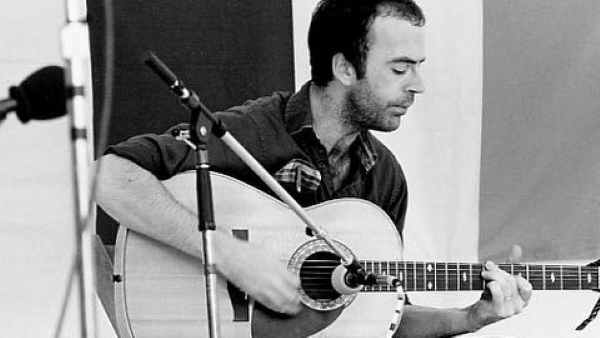

After The Bothy Band broke up, Micheál moved to America, to Portland, Oregon. It was there he rejoined forces with fiddler Kevin Burke and between them the pair reinvigorated Irish music in the city. The duo made two of the best traditional albums ever recorded, Promenade, which won the Montreux Jazz Festival’s Grand Prix du Disque in 1980, and another trailblazing album, Portland. A local DJ called Jewell remembers Micheál well: ‘He talked about the shapes and colours of music,’ he recalled, ‘of how dark a song was. And his guitar playing redefined how a guitar fit into Gaelic music. Plus he was a living, breathing metronome – he drove every band he was in,’ he said.

Micheál often played with his close friend Paddy Glackin and other musicians, and, of course, he was also in two very different bands – Relativity, a mixture of Scottish and Irish traditional music, and Nightnoise, with its more ambient, jazzy sound – but there was never anything short of the highest quality in every project Micheál was involved in.

Other musicians enjoyed having him play with them because his guitar playing style didn’t choke their music. His style was subtle, understanding. As one writer noted: ‘Micheál, like the best jazz musicians, understood that it wasn’t just the notes and the chords which mattered but the spaces in between.’ In these dark days of You’re A Star and Pop Idol, Micheál O Domhnaill was a beacon of hope, a musician who demonstrated that there still existed people who crave excellence, not fame and fortune. It was heartwarming to see him and the others in Skara Brae on that delightful documentary on TG4. It raised our hopes that they had done a few gigs, one in Ionad Cois Locha and another during the Temple Bar festival. ‘What we have decided is to come together a few times a year to do something special. That’s the best way to go about it, doing something we and the audience would be interested in doing,’ Micheal’s sister Maighread told me a few months ago, but that vision some of us had of seeing Skara Brae back at the forefront of traditional music where they belonged will not now be realised.

Micheál Ó Domhnaill, guitarist, composer, and singer, died after a heart attack on 9 July 2006, a few months after his own mother passed away. He was only 54 years old.

Ar lámh dheas Dé go raibh a anam uasal.

Published on 1 September 2006

Robert MacMillan is Irish Language Editor with The Irish News in Belfast.