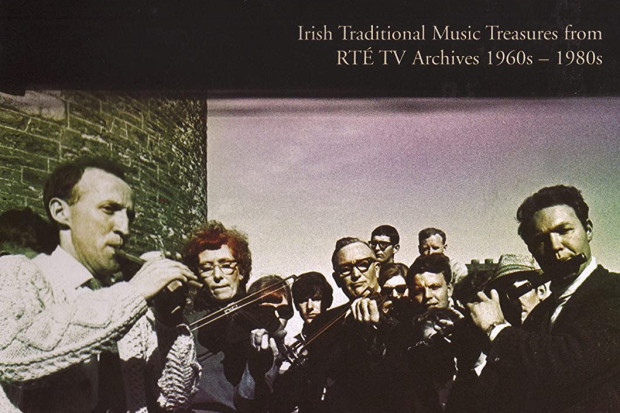

The Aughrim Slopes Céilí Band, winner of the senior céilí band competition at Fleadh Cheoil na hÉireann in 1953 (Photo courtesy of Philip Duffy/On the Night)

Exploring the Rich Musical World of Céilí Band Competition

Almost one thousand pages in length, Philip Duffy’s On the Night: Fleadh Cheoil na hÉireann – Musicians and Senior Céilí Band Winners, 1951–2021 (with two CDs) is ambitious in scope. Duffy, fiddler and Fleadh aficionado, sets himself the task of documenting the biographies of individual musicians in winning senior céilí bands at the All Ireland Fleadh. There are three pillars to the book: biographies of bands/band members; select sounds of winning céilí bands; and images throughout. Combining all three pillars, Duffy builds comprehensive narratives of winning céilí bands and their rank and file musicians, from the first Fleadh in Mullingar in 1951 up to and including 2019. (The convenient chronological range of the title, 1951 to 2021, includes 2020 and 2021, years in which there was neither céilí band competition, nor Fleadh, due to the global pandemic.) Winning names will be familiar to the broader public, for example the Tulla Céilí Band (winning in 1957 and 1960) and fresh in the memory, the Shandrum Céilí Band (three-in-a-row winners, 2015–2017). Other bands may be less recognisable due to the passing of time, even to céilí band devotees, such as the Mayglass Céilí Band (1954, from Wexford). What lies within these pages is a treasure trove of information impossible to summarise. With that caveat, the review here draws attention to broader patterns, conclusions and questions that emerge precisely because of the detail presented throughout.

To the Irish traditional music community of practice, the critical importance of the All Ireland Fleadh, and the comprehensive fleadh system around it, is undisputed if complicated. Festivals are frequently a counteraction to perceived cultural crisis and early Fleadhanna were part of a grass-roots revival response to stark circumstances for traditional music at the mid-twentieth century mark. Organised by a nascent Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann in 1951, the rude health of Irish traditional music globally in the post-revival twenty-first century owes much to the competition-festival model of the Fleadh, and other festival and summer school initiatives that later developed. Though the Fleadh domain is multifaceted, with formal and informal performance elements, competition was central to the identity of the Fleadh from the beginning. Arguably, within that competitive frame, the céilí band competition (one of only seven competitions in the first year) is the climax, acknowledged here in Duffy’s focus. There are complex reasons for the primacy of the céilí band competition, chief among them the collective nature of the performance model and its sustained (if ever-changing) relationship to dance.

Céilí band as an ensemble sound was well established by 1951, embedded at céilís, listened to on the national radio airwaves, and part of competition programming at feiseanna. A performative reaction to modernisation prompted by developing radio and recording technologies, and new public social dance venues, céilí bands in Fleadh competitions elevated the form to new levels, as Duffy notes. The Fleadh created (and creates) a hagiography of céilí band sounds and reputations, extending well beyond the Fleadh space in cultural influence. The dynamic relationship between winning a Fleadh céilí band competition and céilí band performance in the non-festive world is mutually invigorating bringing with it opportunities for performance at céilís, concerts, on broadcasts, and indeed, from the late twentieth century, at festivals nationally and internationally. Duffy describes the benefits of winning céilí band membership stating that ‘many went on to excel as solo performers or composers or to become members of other commercially well-known groups or bands, having originally cut their playing teeth’ in céilí band competition (p. x). Indeed, many musicians come to céilí band success in the senior competition with competition experience already, in various solo and ensemble competition and all come with a high level of musical skill.

Members and names

The author’s catalogue of bands has thirty-six named bands over seven decades. Many won multiple titles in a row such as the Ormond Céilí Band from Tipperary (1979–1981), others had early success and were successful again in later band iterations (the Kilfenora Céilí Band, 1954–1956, 1961, 1993–1995), and some musicians moved from one band to another, winning with both (Mícheál Ó Raghallaigh was part of the winning Táin Céilí Band from 1998 to 2000 and also the Naomh Pádraig Céilí Band, 2004–2006). Duffy provides helpful cross-referencing for just such an occasion. Céilí band membership is only relatively stable. Bands with long lives are, as one might expect, especially vulnerable to changes of personnel. Emigration, pregnancy and other life cycle interventions mean that the band can live on, but with altered membership, speaking to the force of the band as a collective enterprise, beyond individual stakeholders. Over the course of seventy years, bands were frequently put together specifically to compete at the Fleadh, for example the Templeglantine Céilí Band from Limerick who came together first to compete in a Munster Fleadh in Newcastle West in 2007 (the band went on to win the All Ireland in 2010). Competition-motivated establishment for bands was not a new phenomenon (the Bridge Céilí Band, Co. Laois, was set up in May 1970 to compete in the Leinster Fleadh four weeks later, and went on to win three All Irelands in a row), but it does become more common as time goes on.

Townlands and towns, initially dominant in céilí band winner names (Leitrim, Ennis, Brosna, Athlone) gives way to landscape features in naming. Rivers in particular are popular sources of winning céilí band names, for example the Awbeg Céilí Band (2012), named after the river that rises in Limerick and flows into the Blackwater in Cork, and the Blackwater Céilí Band (2018), referencing the Ulster Blackwater, which flows through Armagh, Tyrone and, briefly, Monaghan. The Longridge Céilí Band (1977–78, 1982) ‘is named after the high ridge of land that surrounds the village of Killeigh in Co. Offaly’ (p. 422). Associational names appear on winners’ lists occasionally, such as the Pipers Club Céilí Band (1975, 1976) and references to mythological pasts are also made – the previously mentioned Táin Céilí Band is one. Bands adopt local GAA club names (St Colmcille’s Céilí Band from London who won in 1988 and 1991), music venues (the Thatch Céilí Band, 1986 and 1987 winners) and in one case a bird, the Green Linnet Céilí Band winner in 1971 with a name chosen by Tommy Peoples indicating ‘a bird he very much admired’ (p. 362). By virtue of qualifying rounds in the competition structure, bands are always associated with a particular county, province or region. However, from quite early in Fleadh history, band musicians are drawn from across county, regional and sometimes international lines. Band names untethered to specific townlands reflect the complexity of membership origins in céilí bands. A final note on naming bands (though I could go on), no winning senior céilí band uses a band leader or family name, such as is sometimes found in non-competitive, commercial céilí bands (for example, the Brophy Céilí Band in Dublin) indicative of the particularities of a collective competition aesthetic.

The Brosna Céilí Band in 1972 (Photo courtesy of Philip Duffy/On the Night)

Recordings and pictures

The book has two CDs with a total of thirty-nine tracks providing a summary history of céilí band sounds over the course of the last seven decades. In the Foreword, Siobhán Ní Chonaráin, musician and Comhaltas stalwart, rightly recognises the recordings’ ability to ‘bring to life the stories told within’ the book (p. vii). Recordings, not always recorded in the year of a céilí band’s Fleadh win, are gathered from a number of different sources, among them commercial releases already in the public domain. These commercial recordings are often of bands whose names will already be well known in céilí band circles, for example the Aughrim Slopes (winner in 1953 and the earliest recording included), the Dartry (winner in 2009) and the Tulla (winner in 1957 and 1960). Though all sonic gems (of varying quality), for this reviewer-listener it is the recordings drawn from a variety of media and personal archives, recordings otherwise not readily available or previously collated, that seal their importance to the book. Recorded at Fleadh concerts and competitions, in people’s homes, at céilís, in An Cultúrlann in Monkstown (Comhaltas’ national headquarters), and extracted from radio broadcasts across the island, these recordings animate the narratives of the musicians and bands catalogued throughout the book.

Another animating aspect of the book is the hundreds of archive images included. Enriching the biographical details provided, the amassed pictures range from formal band ensemble photographs and headshot portraits, to more candid shots of individuals, duets or trios playing together on stage, in bars, at home, indoors and outdoors. A number of bands have multiple photographs incorporated which builds a visual timeline of changing membership: the earliest photograph of the Athlone Céilí Band (winning band in 1951 and 1954) is from 1935 and iterations of bands that later emerged out of the Athlone band musicians are also found (for example, a picture of the Ciaran Kelly Band in the 1960s). In formal and informal winning band photographs, a recurring totem is present across the decades: the harp-shaped Dal gCais trophy, awarded to the first-placed céilí band winners annually. Significant too are the photographs that confirm the intergenerational aspect of Irish traditional music-making, musician parents with children, musician children with parents, younger musicians with older musicians, listeners of all ages, each relationship part of the essential underpinning of Irish traditional music life. The broader sociological point is neatly encapsulated under the heading of ‘Wedding Bands’, in the final pages of the book. Here, Duffy gathers together a selection of wedding photos, partnerships established within and beyond céilí bands, but all in the cultural world of traditional music which functions as a crucible of socialisation for those embedded in it.

Instrumentation and female members

Two additional points for this reviewer were offered by the evidence in the book and worth noting: stability of instrumentation and increasing participation of women. Among winning bands only one had a double bass (the Kilfenora in 1956, played by Ita Mulqueeney), there’s others with piano accordions (in the Blackwater in 2018, played by Ryan Hackett and no less than two in the Liverpool Céilí Band in 1963), a few uilleann pipes appear (including Willie Reynolds with the Athlone Céilí Band in 1951), and a single piccolo (Tommy Mallon with the Mayglass in 1954). Though frequently heard in recent decades, banjos up to the turn of the new century were scarce (notable exceptions include Jimmy Ward who played with the first winning Kilfenora band and John Lynch who played with the more recent Kilfenora) and concertinas have grown in representation, mirroring the ubiquity of concertinas today. Overall, however, there is remarkable stability in céilí band instrumentation across seventy years evidenced in Duffy’s findings: fiddles, flutes, a box (or two), piano and drums are the meat and veg of céilí band sounds in competition since 1951.

One of the most significant changes apparent in the narratives and in accompanying photographs, though not explicitly noted by the author, is in céilí band gender composition over seven decades. The Williamstown Girls Céilí Band, winner in 1952, was exceptional on two counts: it was a junior band (there was yet to be divisions of underage and senior) and, as the name suggests, comprised of all girls. Women musicians, when found in the rollcall of céilí band winners in the first two decades, were most frequently piano players (May Moran with the Athlone, Lynda Harper with the Mayglass, Kitty Linnane with the Kilfenora, Evelyn Clince with the Kincora, Anne Marie Courtney with the Leitrim, Peggy Atkins with the Liverpool, and Bridie Lafferty with the Castle). Though scarce, women fiddle players are also listed (Noreen Lynch with the Kilfenora in the 1950s, Aggie Whyte with the 1962 Leitrim band, Kit Hodge with the Liverpool, and Maura Connolly with the Glenside). Kathleen Harrington and her extended family (Pauline and Pat Gardiner) bolstered the ranks of women fiddlers with the Siamsa Céilí Band when they won in 1967–1969, marking a noticeable shift in gender balance, a change maintained and improved upon over the course of the decades that followed. In 1975, the Pipers Club Céilí Band had a majority of women musicians. Women flute players are found from the 1970s on and gender redistribution also means that women box players and men playing piano are, thankfully, no longer exceptions in the Fleadh céilí band world.

Within the broad field of Irish music publications, in terms of detail within a narrow field of interest, the only published comparison to this book which springs to mind is Eddie Kelly’s The Complete Guide to Ireland’s Top Ten Hits, 1954–1979 (2009). Like Kelly’s book, On the Night is an exceptional piece of research and a rich primary resource that I would encourage scholars to build on. As acknowledged in Ní Chonaráin’s Foreword, On the Night will appeal to céilí band and traditional music enthusiasts of all stripes: musicians, researchers, Fleadh aficionados and Fleadh casuals. If I am slightly disappointed that the publication does not extend to 2022, the first year that a Waterford band took home top honours in the céilí band competition, it’s not a criticism, just a clue to my own county origins. Notwithstanding that minor quibble, this tome is a magnum opus. I can’t recommend it highly enough.

On the Night: Fleadh Cheoil na hÉireann – Musicians and Senior Céilí Band Winners, 1951–2021 (+ 2 CDs) by Philip Duffy (2023) is available to purchase from https://onthenight.net.

Published on 8 November 2023

Dr Méabh Ní Fhuartháin is Head of Irish Studies at the Centre for Irish Studies, University of Galway.