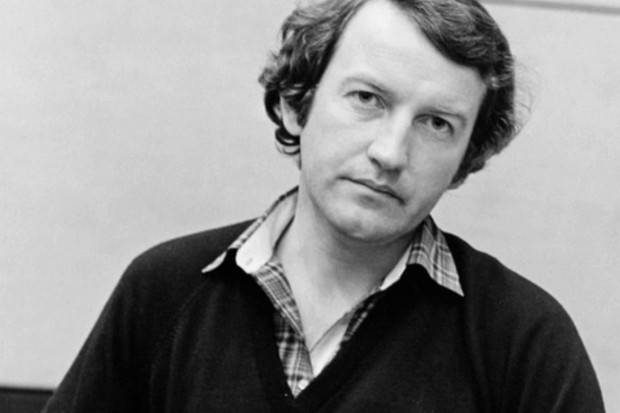

Tom Lenihan, Tom Munnelly and Junior Crehan (Photo: National Folklore Collection, UCD)

'The only thing I am rich in is songs': Tom Munnelly's Lifelong Journey as a Collector

This documentary from producer and director Sorcha Glackin presents a portrait of the life and achievement of Tom Munnelly, something of a legend in Irish folklore circles. As a disclaimer, I must mention that I knew the man well and was fortunate to be able to call him a friend. I benefitted greatly from his mentorship and was glad to see this documentary paying tribute to him.

Tom Munnelly (1944–2007) became, over his lifetime, one of the most prolific professional collectors of Irish folksong in English, and to a lesser extent in Irish. Born into a south Dublin working class family in Clogher Road, family aspirations did not extend to university attendance, as daily existence necessarily took precedence. Though Munnelly’s formal education ended after the Group Certificate, his job in a knitting factory provided him with ample time for reading, which he did widely and voraciously. Coming of age in the early sixties, Tom became involved with the folk revival, then in full swing in Dublin’s O’Donoghue’s pub, among others, such as Grehan’s in Boyle, Roscommon, and at the recently established and hugely popular fleadhanna ceoil, organised by Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann. The enjoyment of traditional music and song in pubs did not necessarily presage a career as a collector, but according to Terry Moylan, Tom’s reading and tremendous interest in the history of folklore and folksong prepared him well for his role as collector. It gave him a perspective well beyond that of ‘just another guy knocking around the fleadhs looking for a bit of crack,’ as Christy Moore pithily puts it.

The cultural value of songs

Tom understood the cultural value and potential of the songs, and his interest in other working class people and their heritage led him to begin recording what he heard. His study and attention were to become decisive in relation to the future direction of his life. Nicholas Carolan makes the point clearly:

He had a natural talent as an archivist. He began to collect information and collect songs. He hadn’t any resources, but somehow he managed to make recordings by hook or by crook.

In the early days, Tom didn’t own a car and hitchhiked to events or to record material from singers. His interest in the songs of the travelling people revealed how this marginalised community still retained a considerable store of what many others in Ireland had left behind on the inexorable march towards educational achievement, material comfort and financial stability in the post-Famine period.

Facilitated by Christy Moore, his meeting with John (Jacko) Reilly (1926–69), a settled traveller from Boyle, Co. Roscommon, proved to be a watershed moment. Tom recognised one of his songs, ‘The Well Below the Valley’, as a version of the Child ballad ‘The Maid and the Palmer’ (Child 21), believed to have been forgotten in oral tradition, and one that had never been documented in Ireland. As Tom became more acquainted with Reilly’s singing he realised that this man, illiterate for official purposes, carried in his head a wealth of ballads, learned orally from his parents in childhood. The meeting cemented his mission as a collector and coincided with a research visit to Ireland by the ballad scholar D.K. Wilgus of UCLA. Recognising Tom’s ability and talent, Wilgus appointed him as his assistant.

With that imprimatur, Tom was later hired by his friend and mentor Breandán Breathnach for a song collecting scheme through the Department of Education in 1971. (The late Seán Corcoran was the other collector appointed.) This project became part of the Department of Irish Folklore in UCD after four years, with Tom being appointed as a permanent collector. His passion for song and his commitment to social justice never wavered. It took him to homes all over the island, in his attempts to document and collect hidden traditions of song that flourished in unlikely places, such as Inishowen, Co. Donegal. He and his wife Annette moved their children to Miltown Malbay in Clare in 1978, and from this base Tom continued his tireless work until he succumbed to illness in 2007.

Halcyon days

Sorcha Glackin and her team bring the rather dry summary above vividly to life, using a variety of rich archive sources from the National Folklore Collection, Irish Traditional Music Archive, RTÉ, and a host of others, combined with interview excerpts from those who knew him well, to assess the impact Munnelly made on the song traditions of the island. Though this format may appear traditional and even conservative, it is nevertheless highly effective.

Archive footage of the halcyon days in O’Donoghues, of huge crowds frequenting the fleadhanna and other gatherings infuse a dynamic vitality into the story, conveying the excitement and hedonism of this time. We are left in no doubt as to what Tom’s wife Annette means when she claims ‘it was like a party all the time.’ At one point, Séamus Ennis appears playing the whistle with a cigarette in the corner of his mouth at the same time! The verbal sketches by the contributors who describe the period come alive as the archive footage skilfully matches their narratives. For Munnelly, that excitement and enjoyment translated into a focused, lifelong passion for folklore and song. Annette mentions Tom’s regret as he endured his final illness that he would never finish the work, but reflects that he would never have finished it anyway, as he always turned to new projects as others ended.

The enduring affection that those interviewed retain for Tom Munnelly emerges palpably, most poignantly from Annette and from her brother Jerry O’Reilly. She is candid and forthright about their life together and about the challenges they faced. Both believed strongly in the mission to collect and save the songs for posterity. When Tom received an honorary doctorate from the University of Galway in 2007, the same year he died, she records that Tom said, ‘this is for Martin Reidy and Tom Lenihan and all the other people I collected from. They’re the ones who deserve this honour, not me.’ The love and passion persisted to the end. Nevertheless, Annette never shies away from Tom’s strong personality and his sometimes contentious relationships. Tom chose a wicker casket for his coffin, a style not then yet widely in vogue in Ireland. Annette remembers laughingly that a friend who came to pay respects addressed him disapprovingly as he lay in his coffin: ‘So there you are, Munnelly! You were always awkward, yourself and your Moses basket.’ Tom’s capacity for gallows humour is well illustrated in the interview excerpts by Paddy Glackin, Nicholas Carolan, Cathal Goan, and most of all, Annette herself, as the above vignette shows. His seriousness as a teacher and scholar, and his respect for those whose songs he recorded is similarly noted by Ríonach uí Ógáin and Thomas McCarthy, who praises Munnelly’s recognition of John Reilly’s talent, by having a commercial recording made of his songs and having him invited to the prestigious Tradition Club in Slattery’s of Capel Street. McCarthy’s own performance of ‘Johnny Varden’, a version of Child 100, ‘Willie O’ Winsbury’, given in full, is a special highlight.

Lisa Lambe’s encounter with Munnelly’s archive and her touching account of listening to the 1971 recording in which Tom documented ‘Matt Hyland’ from Margaret Dunne of Ballinagh, Co. Cavan, mother of eleven and grandmother of fifty-one, gives valuable personal insight into the motivational potential of these audio recordings. Lambe’s description of how the immediacy of the recording touched and inspired her provides another memorable vignette, showing how Munnelly’s collection provides material for contemporary singers as well as for scholars and academics. Given his own beginnings as a fan of the folk revival, this would surely have pleased Tom.

Though it is an hour-long documentary, the portrait is necessarily brief. Some singers said to him: ‘I have always been poor and I’ll probably die poor. The only thing I am rich in is songs, and I am glad I can pass them on.’ Thus, the scope for other programmes based on Munnelly’s life and work emerges clearly. When he began his collecting, neither Raidió na Gaeltachta nor TG4 existed, nor the host of local radio stations now broadcasting. I hope that others with the talent and vision of Sorcha Glackin delve further into this rich trove to tell more compelling stories from it.

To watch Fear na n-Amhrán: Tom Munnelly visit www.tg4.ie.

Published on 10 January 2024

Lillis Ó Laoire retired from his post as professor of Irish at the University of Galway in 2023. He has published widely on song. His most recent book, a collection of essays written in Irish and Scottish Gaelic, edited with Philip Fogarty and Tiber Falzett, is 'Dhá Leagan Déag: Léargais Nua ar an Sean-nós' (Cló Iar-Chonnacht 2022).