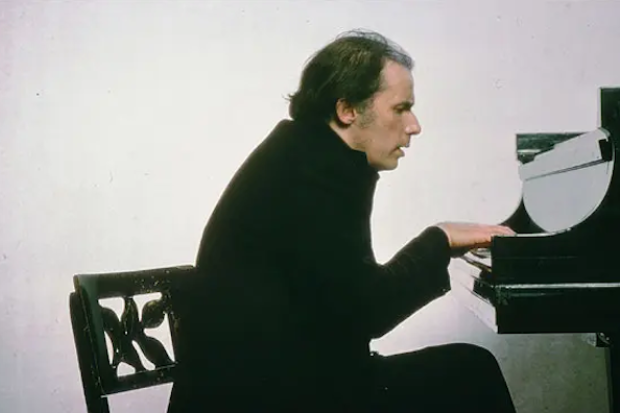

Bridget Cunningham (Photo: Victoria Cadisch)

Bringing to Light a Forgotten Anglo-Irish Composer

The Anglo-Irish composer Thomas Roseingrave was celebrated enough in his eighteenth-century London that his fall into almost complete neglect is worth challenging. Bridget Cunningham, harpsichordist and expert on this historical period, has taken this challenge upon herself and found a composer worth championing; this double CD, Thomas Roseingrave: Eight Harpsichord Suites and other keyboard works, is her attempt to resurrect him.

Roseingrave was born in England in 1690 or 1691. His father, Daniel Roseingrave, moved the family to Dublin in 1698 so that he could become the organist for both of Dublin’s cathedrals. (The Roseingraves were a musical family: Thomas’ brother Ralph inherited these posts.) Thomas spent the rest of his childhood in Dublin and started a degree in Trinity College; he did not finish, and in 1709 moved to Italy, where he met Domenico Scarlatti, whose music he would later successfully champion. He returned to Ireland in 1713 but soon moved to London, and by 1717 was established in the London music scene as a harpsichordist, music teacher and music editor, even becoming the organist at G. F. Handel’s parish church in 1725. Latterly, he seems to have taken very hard his would-be bride’s father forbidding her to marry a musician, and he retired early, moving to Dún Laoghaire in 1750. Roseingrave seems to have had some musical life in Dublin, but it was not the success of his time in London. He died in 1766 and is buried in the churchyard of St Patrick’s Cathedral in the family grave.

The music Cunningham plays on this album was written during Roseingrave’s thirty-odd years in London, and he could not have asked for a better exponent. This might partly be because of her own Anglo-Irish identity, but it is certainly because she is an expert on British and Irish music of this period. As harpsichordist and as conductor of her ensemble London Early Opera, she has released several albums (all with Signum) of music by Handel and those in his milieu, including, in 2016, Handel in Ireland, Vol. 1 (we are still awaiting vol. 2). In her previous work, Cunningham has balanced a comprehensive knowledge of the music and its social context with a mature excitement for it. This proselytising fire burns bright on the present recording too, as well as in its substantial and helpful liner notes. She plays with total command but also with jubilance and constant invention, adding not just ornaments and arpeggios to Roseingrave’s score, but runs, figures and even cadenzas. In the great (but historically defensible) license Cunningham takes with the score, she has a perfect sparring partner in Roseingrave, who was a famous improviser in his day. Listen to the prelude to the second suite – now consider that the score for this movement is little more than block chords.

Short works

As well as the eight harpsichord suites Roseingrave published in 1728, Cunningham presents several other short works of his that give a broader picture of his compositional style, and one work not by him at all. That work, called here ‘Celebrated Lesson for the Harpsichord’, is by Domenico Scarlatti, though edited and arranged by Roseingrave and published in 1750. The reason for its inclusion is that it gives more insight into Roseingrave’s playing style and by extension that of eighteenth-century Britain. But it is also exciting to have what is as far as I can tell a premiere recording of a Scarlatti work: if this ‘Lesson’ is one of his 555 sonatas, I don’t recognise it.

Roseingrave’s suites are strange things. Many of the movements seem to only state their themes before they’re over, and some of them overstay their welcome. One wonders, during some of the shorter or more monotonous movements, whether Roseingrave departed from his score even more than Cunningham does. For example, the Adagio to his ‘A Celebrated Concerto’ (elsewhere known as the ‘Harpsichord Concerto in D Major’) is only seven bars long and the penultimate chords are marked ‘Ad libitum’. Cunningham does get a lot from these chords, but the movement is still so unsatisfying in its brevity that I speculate that Roseingrave the great improviser went even further, making a substantial movement out of those chords, perhaps making each a key in which the stated theme is developed.

Another peculiarity of the suites is their unsystematic structure. Even more than Purcell’s and Handel’s sets of eight suites, each is unpredictable: some end with sarabandes, some consist of only three short movements while some have five. They are not unfinished, but they are a world apart from the rigorous design of Bach’s harpsichord suites.

As such, despite Cunningham’s laudable efforts, I remain lukewarm on Roseingrave as a composer. This said, the music here is always pleasant, very often interesting and sophisticated, and more than occasionally brilliant. The fourth suite is convincing throughout and not less so because it ends with a stately sarabande. The first suite’s French overture and Scarlatti-influenced presto have some lovely surprises, as does the first movement of ‘A Celebrated Concerto’, and there is some delightful chromaticism in the gigue to the third suite. Cunningham’s interpretation casts an exceptionally flattering light over Roseingrave’s music, it’s true – but not a distorting light.

Thomas Roseingrave: Eight Harpsichord Suites and other keyboard works by Bridget Cunningham is available to purchase on CD from Signum Classics. Visit https://signumrecords.com.

Subscribe to our newsletter.

Published on 4 April 2024

James Camien McGuiggan studied music in Maynooth University and has a PhD in the philosophy of art from the University of Southampton. He is currently an independent scholar.