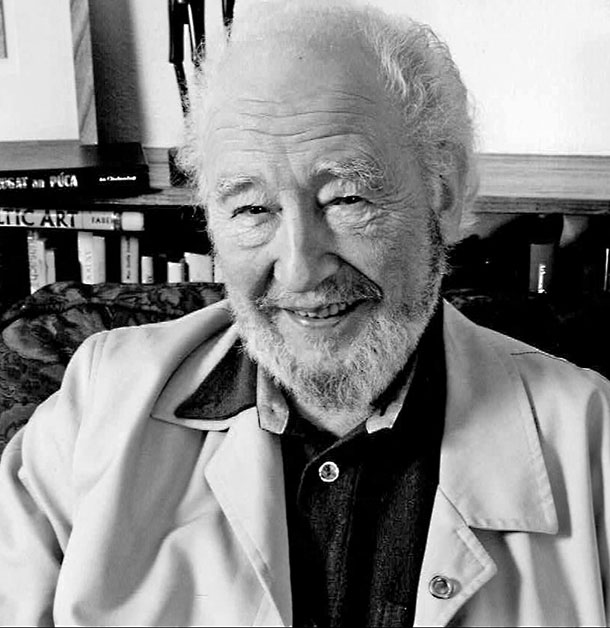

Deasún Breatnach

Geantraí, Goltraí, Suantraí

‘But is it a living tradition?’ Irish traditional music was the target, and the question came as I was leaving the lecture room of the Music Centre, Temple Bar, Dublin, in April 1996, having contributed in Irish to Crosbhealach an Cheoil, a series of lectures and discussions of the music in both Irish and English. Why the title? Because the music was at a crossroads, allegedly.

‘You mean geantraí, goltraí and suantraí?’ I countered. During my clock-bound lecture I had pointed out, in hurried references, that no great a person than the Dagda himself had had a part in the invention of that trio (at least, in one account in Old Irish); and, by the way, Fintan Vallely, did your man get an invitation to read a paper?

In one ancient account the cruit obligingly moved of its own volition to the Dagda (supremo of the Gods), whereupon he played these three kinds of music, happy, sad and hushabye. According to Fergus Kelly (A Guide-to Irish Law; Dublin, 1988-1995), the cruitire, or harp player, the only entertainer in early Irish society with any respectable legal status, was required by law to be a master of the geantraí and its two companions.

So I was able to reply that of course it was a living tradition, going back a long time. Most mothers sang lullabies to their children. I had done so in Irish for all six of ours; and my wife had contributed her selection in Castillian Spanish. On the arrival of our first grandchild, Sorcha, being unable to sing to her because she was in far away London, I had composed music and lyric.

‘Did you copyright them ?’ asked a voice from the crowd. ‘Because if you didn’t somebody will steal them!’ Copyright, pros and cons, had been a hot subject for debate in-lecture rooms, and over glasses, later. Well, they are covered because they are in print in Dánta Amadóra, my collection of poetry (1998). And since then that tradition has been continued with my great-grand-daughter Aoife, bless her.

Of course, I cannot guarantee that everybody sings lullabies to his or her young, though I would hope so. As for geantraí, go into half the pubs of Ireland after about 22.00 hours and you’ll hear the geantraí by the score, for this is the happy sound of jigs, reels, hornpipes, polkas, strathspeys, which help us not to remember the weather outside while getting the feet a-tapping (or a bodhrán, or a pair of spoons, if you have them handy).

The goltraí is a wee bit of a problem, firstly because publicans are not keen on having their clientele crying into their glasses as the wandering cruitire plays the sad, sweet notes as he comes in the door.

Some publicans tend to be a bit cagey, also, where singing is concerned. You might think that Section 31 is gone, or rather strictly controlled. Not so.

The goltraí properly covers a wide ground, in subject matter and history, and some people might fear it as a rabble rouser. It may be honoured by string, wind, voice, or whatever. Before the time when I was required. to sing my children to sleep, and when I played publicly, if only occasionally, the fashion was to play a slow air, or even a hornpipe such as ‘The Rights of Man’, and follow that with jig or reel.

At the sessions which I attend when I can, the custom now seems to be to avoid the slow air, more’s the pity, and to try to avoid a pause in the music lest a singer intrude. That, certainly, is a break in tradition.

There is also the nasty habit of tuning fiddles in such a way as to keep out the feadóg. There, if you like, you have a crossroads, certainly as regards the singing, for the whistle player is well able to take care of him (or her) self.

To hear a bit of singing, except on very special occasions and in very special places, one must visit the Gaeltacht, or buy a tape recorder. Some future Crosbhealach must confront the singing problem so as to make it once again part of the public presence of Irish traditional music. And what a wonderful collection we have, especially the great songs of Munster, the likes of ‘Bean Dubh a’Ghleanna’ and ‘Caiseal Mumhan’!

‘You were saying… ?’ insisted that man, as we headed for the last round-up under Cathal Goan.

‘Well,’ I replied, ‘I’m alive, even though it might not always seem so; and I have composed, played and sung the suantraí; and I can say the same for the geantraí, even if it was a while back; and, as for the goltraí, I suppose I have done more for them than anything else.’

Yes, the tradition lives, in both languages, even if some of it might be stronger, less confined, far less shy.

That weekend six years ago in that splendid Music Centre was very well attended. Points were made, often with dedication. The media received well deserved criticism. All of us felt the better for it. No longer do we feel alone, marginalised, timid about our democratic rights. Go deimhin, éireóchaimid aríst!

Published on 1 May 2002