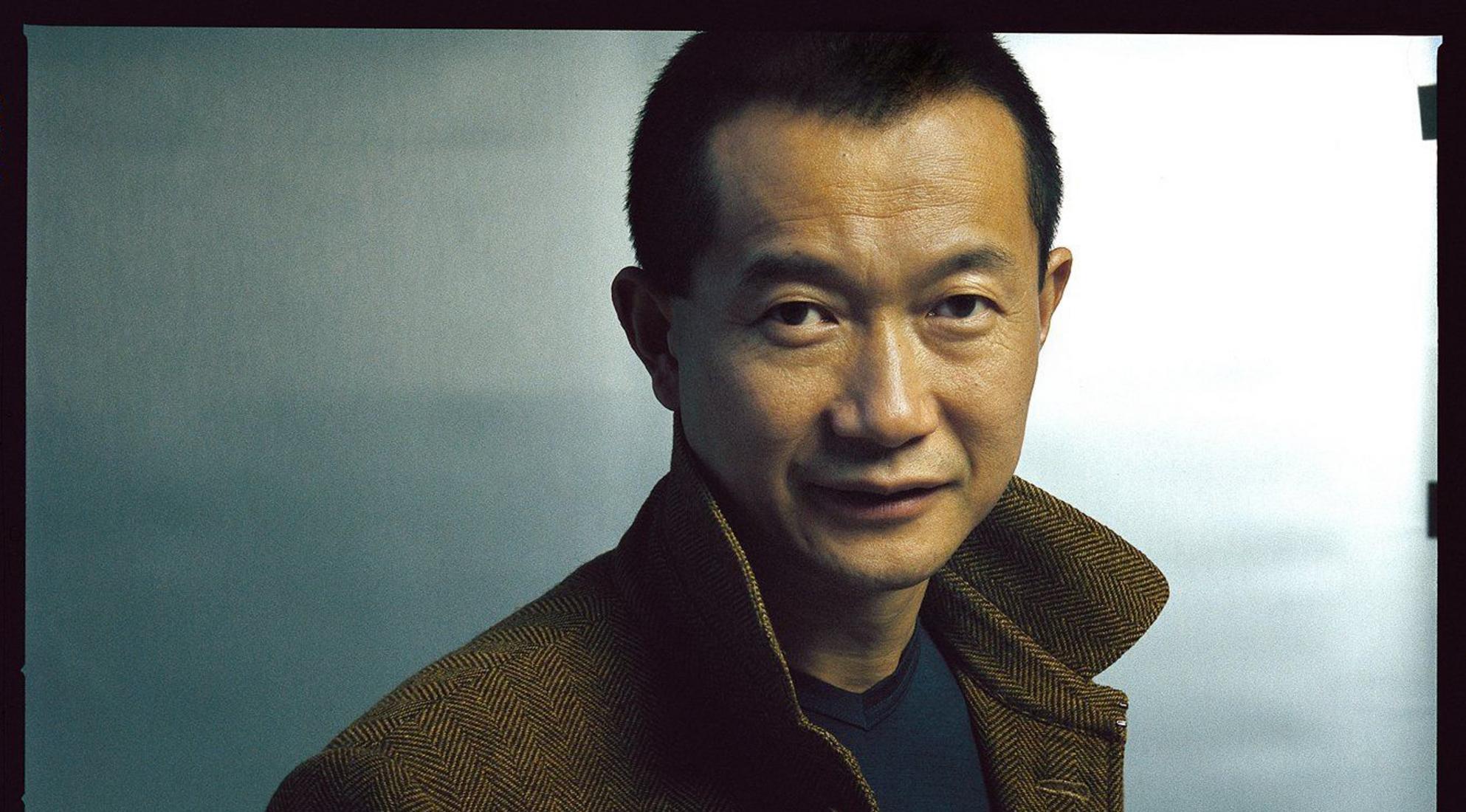

Tan Dun

Live Reviews: Gig! – Crash Ensemble

Project Arts Centre, Dublin

20th December 2001

The last concert given by Crash Ensemble as part of their residency at Project Arts Centre took place on Thursday 20th December. This concert programme epitomised the whole philosophy of Crash, combining Irish premiere performances of recent works from international composers with those of Irish composers.

The opening piece was Tan Dun’s Concerto for Six. Tan Dun is best known for having won an Oscar for the musical score of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. This work consisted of one movement, a lighthearted game with a strong percussive drive whose rhythm varied to a number series. The overall effect was as if the music had been written for the jerky dance movements of a puppet and its visual, humorous, quality was reinforced by the shouts of the performers. This is not a strongly engaging piece of music, but the Crash Ensemble made good use of the sections for free improvisation, especially impressive was Malachy Robinson on double-bass.

Robinson, as well as being the principal double-bass with the Irish Chamber Orchestra, is also a composer, and his own String received a world premier as the next piece on the program. String is a quartet dominated by the double bass and snare drum. It opened seemingly as an intellectual exercise in rhythm, but then it took off and at one point, as all of the instruments were speaking with their deepest, slowest, voices the hairs on my neck were beginning to rise. Frustratingly, like a sneeze that doesn’t come, a sudden turn in direction left the moment unfulfilled Crash returned to the work of New York composer Julia Wolfe for their third piece, Girlfriend. The core of the work consists of a looping and rearranged recording of a car crash, around which the other instruments slowly rise and fall in a minor key, lament-like in their movement. It is a difficult piece to match tape to instruments, and Crash performed it expertly. The tape is very graphic – to the point that you can hear, after the thud of collision, the sound of a body going through a windscreen. It is really this sound, more than the music around it, which produces an aesthetic response. If you believe this music is of an actual crash, then the effect is like that of seeing Warhol’s photograph of a car crash, repeated over and over, sickening yet morbidly fascinating. If you don’t believe that the composer is referring to a real incident in her life, then the piece does not engage at all. In either scenario – and as you listen you alternate between the two states of mind – for very different reasons, it is far too long.

After the interval came the world premiere of Raymond Deane’s Passage Work. The background to the work, as discussed in the previous issue of JMI, is important – this is a programmatic piece inspired by thoughts arising from contemplating the memorial to Walter Benjamin in Portbou, Catalonia. There, in 1940, one of the twentieth century’s greatest philosophers killed himself, convinced that he was about to be given over to the Gestapo. Right from the beginning, the music is shockingly violent, as befits its subject. The shrill, staccato of the soprano is joined by instruments and taped sounds in an aggressive assault on your senses. Just as it must be hard on a modern battlefield to cope with the frightening sounds around so, with this music, it is impossible to keep your balance. And the few sounds that you can easily come to terms with are hardly reassuring – such as a heavy taped footfall that evokes the monument to Benjamin by Karavan, which is an iron staircase descending to the sea. Although the intensity of the opening does ease, the sounds soon thunder again, until suddenly and unexpectedly the work finishes. This is not the kind of music that you would play over and over, but, it was the one work in the concert that I would go out of my way to hear again, live if possible. The performance by soprano Sylvia O’Brien was extraordinarily impressive, particularly as she had stepped in at short notice.

The subsequent piece, No.24 by Richard Ayres, was a welcome opportunity to hear his work for the first time in Ireland. It provided light relief to that of Raymond Deane and the audience laughed aloud at the comic expressions of Roddy O’Keeffe on trombone. As a ‘NONcerto’ the music was deliberately theatrical and amusing, particularly in the sounds given to the trombone, but after a few minutes the joke wore thin. The final work on the program was Donnacha Dennehy’s own To Herbert Brun. Originally a collaboration with the Daghda Dance Company, for the most part it did not stand too well alone. The fourth and final part seemed interesting, particularly in the use of a heavy percussive electronic bass sound, which was not taped but trigged by the musicians. But it would have been hard to engage with any piece while still in shell shock from Passage Work.

Published on 1 January 2002

Conor Kostick is a writer and journalist. He is the author of Revolution in Ireland (1996) and, with Lorcan Collins, The Easter Rising (2000).