Live Reviews: The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant

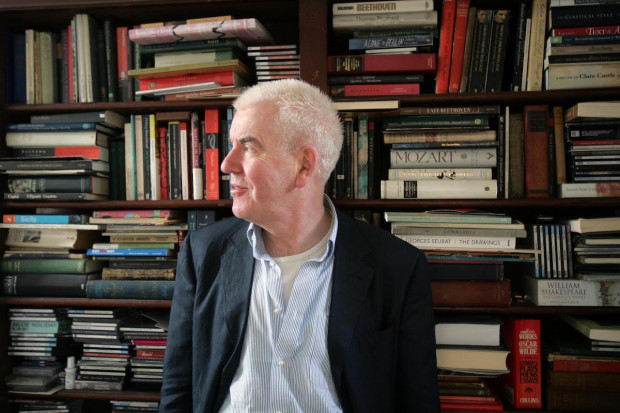

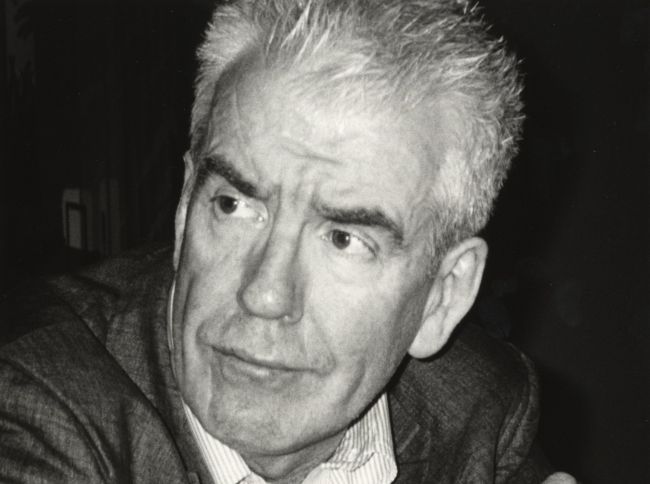

Gerald Barry

The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant

(Friday 27 September 2002, world premiere, RTÉ Music Commission)

National Symphony Orchestra

Gerard Markson, conductor

Orla Boylan, soprano

Mary Plazas, soprano

On Friday 27th September the National Symphony Orchestra with sopranos Orla Boylan and Mary Plazas performed the world premiere of Gerald Barry’s Act II of The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant. This was the first commission from RTÉ to one of Ireland’s leading composers, a long overdue invitation, the piece fortuitously arriving in the year of Barry’s fiftieth birthday. The piece will also be performed on 1st December at the Huddersfield Festival of Contemporary Music, after which it will not be heard again until the whole opera is performed or until the Fassbinder estate softens its strict desire to keep the text complete in the light of the needs of concert programming.

Barry’s work is inspired by the tragic tale of Petra von Kant whose obsession with a much younger, but much more knowing and ruthless Karin ends in rejection and in Petra’s disintegration. For Barry the text is rich but complete, no alteration at all has been made in order to form the libretto as ‘the Fassbinder text is a masterpiece, nothing is extraneous’, he told the audience at the pre-concert talk.

It is ten years since Barry’s last opera, ten years in which this subject has been in his mind, but until the opportunity provided by RTÉ’s commission, it had not been developed. Curiously Barry has begun with Act 2 as a calling card to solicit interest in the whole project, ‘because it introduces us to the character whose world is going to collapse.’ The other four acts are not yet written.

Now the interesting challenge of the text is that while the chat between Petra and Karin is inane at times, Petra is covering a nervous welter of emotion that bursts to the surface at the end of the act with a declaration of love. Before the piece began, conductor Gerhard Markson explained that at times the music would drown the libretto, this being by design, as the music was expressing the inner world of the characters.

The work opens with a great deal of excitement and nervous tension, where the energetic reiteration of the theme tells us everything about the state of mind of Petra. There are jumps in the music that feel like your throat catching from a racing heart, and for the early part of the Act Barry’s interpretation of Petra through music is compelling and involving. The contrast with Karin is effective too, far less of the orchestra accompanies this more placid figure, in particular the high pitched percussion, which hints at nervousness to the point of breakdown in Petra, drops aside for Karin, who also has a vaguely sinister undercurrent of music to her seemingly banal conversation.

But as the piece continues, one of the disadvantages of taking the text exactly as it appears in the play emerges, which is that the exchange of very short pieces of conversation leads to disjointedness as the music swells up and disappears over very short intervals. It is like hearing an orchestral Morse Code signal.

The state of nervous tension expressed by the music also becomes problematic as the piece continues. How long can we sustain this anxiousness and obsessive pressure? Barry opts to continue it for the full twenty-four minutes of the Act. But this is probably a mistake as some nuance and texture would have made the piece far more involving for an audience whose attentiveness seemed to wane under the constant intensity of the opera. As it is, the musical contrasts, such as an extensive progress up the scale for Karin as she begins to speak on more serious subjects, are all framed within this sense of nervousness.

To be fair to Barry, having once begun with the idea of a dialogue between the bland conversation and the beating of Petra’s heart, then for rigorous consistency this method needs to be applied throughout – or at least until the pattern of conversation changes as it does towards the end.

The text is enlivened by bitter humour, evident to an audience but unconscious to the characters, this Barry reflects musically, in sharp unexpected musical moments – but it is, like the text, a humour without playfulness and rather lost in the general anxious rush.

If this Act, the one in which the ‘world is still smiling’, to quote Barry, consists of music of a driving, intense, disjointed feel, it is difficult to imagine where he will take the more overtly tragic scenes.

There is beauty to the opera, but it is the austere beauty of artic cliffs or a craggy lunar landscape rather than the delicate Mussorgsky that the concert programmers so thoughtfully provided either side of the The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant.

Published on 1 November 2002

Conor Kostick is a writer and journalist. He is the author of Revolution in Ireland (1996) and, with Lorcan Collins, The Easter Rising (2000).