Laura Sarah Dowdall in The Worlding (Photo: James Connolly)

Everything Strange

Jennifer Walshe’s Aisteach project was launched in 2015. It is an imaginary history of the Irish avant-garde, a group of sound artists, musicians and composers inserted into the cracks of history. They invented drone music, they were the improvising Guinness Dadaists, or the elusive Caoimhín Breathnach and his Golden Cassette, or a nun performing avant-garde music on Church organ.

Aisteach – meaning ‘strange’ in Irish – is not the first group that Walshe has created; Grúpat from 2007 to 2009 consisted of a 9-person collective of sound artists, all Walshe. She said in a recent talk that Irish culture is fertile ground for such re-interpretations – ‘It doesn’t seem imperialistic’ to play with Irishness. Everything has happened, and anything could happen, in our history.

Aisteach, to date, has been: work by various artists (all Walshe), a book with many contributors (not all Walshe, but curated by her), and an online archive (of all) – but now it has been given another dimension in an exhibition at the Model arts centre in Sligo that runs until the beginning of November. Commissioned by Emer McGarry, the exhibition contains not only Aisteach work by Walshe, but also that by other artists curated by her, such as Vivienne Dick and Alice Maher.

This is the first time that Walshe’s oeuvre – which is in the vanguard of what is happening internationally; her work was described as ‘fascinating’ by Alex Ross in the New Yorker in August – has been extensively celebrated in Ireland, and it comes from an artistic space at the edge, in the north-west of Ireland, not Dublin.

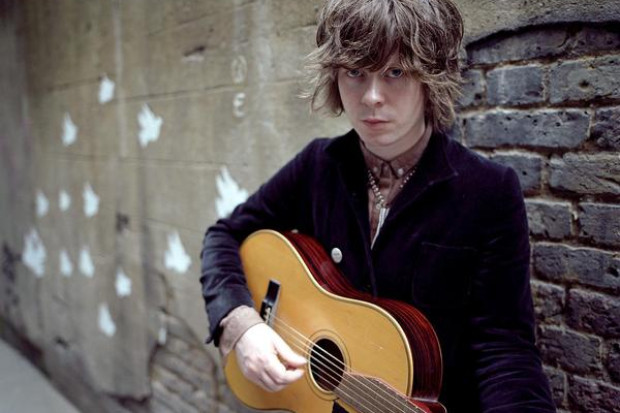

Aisteach at the Model began on 31 August with the world premiere of a performative installation devised by Walshe in collaboration with the new music vocal group Tonnta (Robbie Blake – director, Elizabeth Hilliard, Bláthnaid Conroy-Murphy, Simon MacHale and Tristan Caldwell), plus Natasha Bourke, Ruairí Donovan and Laura Sarah Dowdall, with costumes by Electronic Sheep. The Worlding is where Aisteach comes alive, out from the walls and pages and into your mind.

Laura Sarah Dowdall and Natasha Bourke (Photo: James Connolly)

Here and now

We begin in the largest of several rooms. Around us are elements of the exhibition, beginning with a soundpost for a drone album by Pádraig Mac Giolla Mhuire, collected in the 1950s by Cnuasach Bhéaloideas Éireann – the national folklore collection. At the end of the room are three people (Tonnta) sitting around a table, taking turns to whisper into a microphone. We can make out the Irish words ‘anois’ (‘now’) and ‘anseo’ (‘here’). Another member sits staring at a wall, searching for sounds with a stethoscope. Two others enter with pieces of silver insulating material, waving and crumpling them in the air, moving through the room, obsessed.

We move into the next space, where there are recordings by Sr Anselme O’Ceallaigh, titled Virtue IV (1972) and a vast collection of holy water in plastic bottles, all labelled by townland. The walls at each end are covered with works of ’Celtorwave’, an online art micro-genre. Celtorwave fuses the early 1980s and the distant past, the Telecom Éireann logo against a wash of flowers and blue water, a Sheela na gig carving against a microchip. A man and a woman walk through the room, silently playing bridge-less violins with long thin-leafed branches. Another lowers herself from the ceiling by rope into an ancient stone circle.

To the side is a tent with a camp-bed, and an invitation to lie down and listen. It’s the ritualistic work of Caoimhín Breathnach, buzzing in your head. Beside is a cage holding nuts, rocks, seeds and a sheep’s jaw bone. Further down the corridor, Elizabeth Hilliard is repeating vocal patterns beside ‘haunted mirrors’ – mirrors people wanted to get rid of but couldn’t bring themselves to. She stands beside them and recites from a page: ‘fumsbabatakya… dumafumsfafaoohey… cibey, cibey, cibay, cibay, cibeee! Danum… kschhhh… yawww… beeteeel… danum… ayawwwww… danum… mm…kschhzz…’.

In the Aisteach ’reading room’, in a glass case, the words ‘anseo’ and ‘anois’ appear again, in notes for a science fiction story titled ‘Cealgarraidhe’ by Áine Ní Dhomhnaill aka Phillipa Byrne. On the left of the page is a time-line of twentieth-century Ireland written in Gaelic script, in which there is a coup d’etat in the United Kingdom in 1933 and an attempt to establish a republic. On the right, there is a diagram of time delineating ‘An Domhain le Teacht’ (‘the world that is to come’) and ‘An t-Am atá Thart’ (‘the time that is over), and lines drawn to ‘Anois’, ‘Anseo’, ‘Spás’ (‘space’) and ‘Solas’ (light’) and a mathematical formula.

Elizabeth Hilliard (Photo: Heike Thiele)

Bang snaps

After 40 minutes, via Caoimhín Breathnach’s An Gléacht film with close-ups of rituals with stones, insects, a mouth with shells and a St Brigid’s Cross, we return to the beginning. Four members of Tonnta are seated. They are turning over dozens of white cards that have words such as ‘wedding’, ‘young’ and more. The four then hurriedly look through their Irish folk-song books until they find that word in a song. They throw ‘bang snaps’ – the little bangers children play with at Halloween – on the ground and start singing solo. It is patterned and ritualistic. As soon as they arrive at the moment in the song with the word, they abruptly stop, then start the ritual over again. Every now and then, all four stand up and break out into a perfect a cappella version of ‘Danny Boy’. A troubled, red-bearded man with no shirt keeps running in and pointing towards them. A woman in an elegant dress is rushing up the stairs and through the rooms, over and over.

The hour-long The Worlding climaxes when the group move to the centre of the room – two sitting with hands clasped like traditional sean-nós singers, two others standing with their hands on the singers’ shoulders, one kneeling. ‘Oh the wind and the rain’, Tonnta sing in repeated, circular fashion, their endless mixed-up words smothering any meaning. It is like a pub singing session, familiar but complex, returning over and over to the ‘wind and the rain’ and squeezing each other’s hands with every refrain. It builds.

The troubled man comes and kneels with his back to them, reaches into a bowl of berries, crushes them and lets the juice roll down his torso. A lady in a dress comes with mouth gaping wide but says nothing, arms outstretched. Tonnta leave. We are left with the man and lady in silence. It’s like Walshe has rolled a dice of Irish culture and embraced whatever has come up. Everything is strange; everything makes sense.

In one sense, the Aisteach exhibition is a retrospective of recent work by Walshe, and a welcome one, displaying the breadth of her imagination and originality. It is the listening posts which give the fullest sense of her many directions.

The Worlding, though, is transformative, and, in its expanse, different to works such as Dordán, or her solo piece with electronics, ALL THE MANY PEOPLS. There is something so present about The Worlding. In a post-Troubles, post-Catholic, post-Celtic Tiger Ireland, trying to please everyone, our culture moves forward, eager to conform. Walshe seizes it as a period of re-imagining. The Worlding and Aisteach – wild, brave mesmerising leaps – show us what is possible.

Aisteach runs at the model until 4 November. Visit http://themodel.ie/exhibitions/jennifer-walshe-aisteach.

Published on 6 September 2018

Toner Quinn is Editor of the Journal of Music. His new book, What Ireland Can Teach the World About Music, is available here. Toner will be giving a lecture exploring some of the ideas in the book on Saturday 11 May 2024 at 3pm at Farmleigh House in Dublin. For booking, visit https://bit.ly/3x2yCL8.