Alexander Hancorn of the Royal Academy of Music, London, performing as part of New Music Dublin (Photo: Molly Keane)

Excellence But Lacking Surprise – New Music Dublin: Days 2 and 3

For a review of days 1 and 4, see here.

***

The Friday and Saturday of New Music Dublin featured a characteristically diverse range of music, including two substantial world premieres by Linda Buckley and Bekah Simms. Most of the concerts featured regularly featured musicians: we had two orchestral concerts by the National Symphony Orchestra, world premieres from Chamber Choir Ireland, a retrospective of Gerald Barry’s chamber works, Crash Ensemble’s composer development programme, and Diatribe stage’s night slot. We also had cult ambient duo A Winged Victory for the Sullen and the climate-change-inspired free improvisation of Natalia Beylis and friends, plus a free lunchtime concert in Dublin Castle and Brian Irvine’s Totally Made-Up Orchestra.

Gerald Barry in Focus

Friday opened with a concert of Gerald Barry’s music for violin and piano. Performed by Darragh Morgan and Mary Dullea of the Fidelio Trio, the programme was mostly taken from Fidelio’s 2022 In the Asylum (which the Journal reviewed at the time here). The only addition was the world premiere of Four Etudes (2024) for solo violin. These brief pieces were Barry at his most terse and abstruse, and did not open themselves to me on first listen. Morgan and Dullea’s performance, needless to say, was superb, capturing Barry both at his most hermetic (as in Baroness von Rikart) and his most ebullient (as in Le vieux sourd).

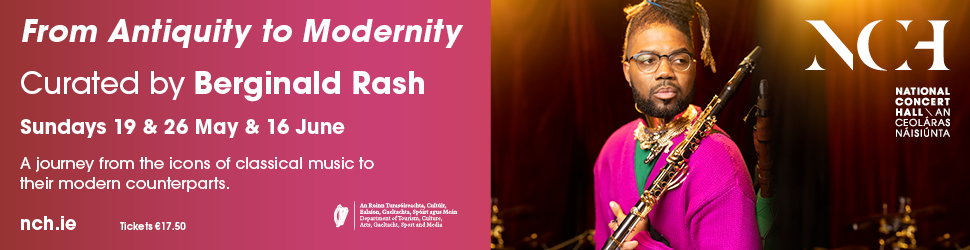

You Heard It First: Crash Works

A fixture of New Music Dublin for the past few years has been Crash Ensemble’s ‘Crash Works’, in which we get two hearings of new works by five young composers: first when the pieces are in their infancy and then again the following year when they are ready for their official premiere; the works are written in collaboration with and under the mentorship of Crash over the course of the programme. This year, we heard the first outing of works by Lara Weaver, Cathal O’Riordan, Aleksandr Nisse, Tim Doyle and Aoife King. As Crash’s director Ryan McAdams was at pains to point out, these works are unfinished, in some cases still only sketches, and I do not wish to prejudge their potential. I will say, though, that I was heartened by their variety. Weaver’s work is inspired by the huge sounds that shifting sands in the Arabian desert produce, O’Riordan’s by our genetic similarity to one another, Nisse’s by forest ecosystems and tuning systems, and King’s theatrical work by the Kerry sea; Doyle joins the many braves trying to connect Irish traditional music to contemporary classical music.

Two things stood out to me as places where all five composers could focus their energies in developing and refining their works. First, I would remind them that a good concept goes absolutely no way at all to making good music. It can orientate a listener, guide them towards a mode of engagement – after that (and really all the hard work is after this point), the music has to work on its own terms. Second, all the music we heard at this concert had a slow, steady rate of change. There’s nothing wrong with this, but a more elastic approach to time can also be fruitful. The ear is very intelligent: with the right treatment, a note or passage can seem much longer or shorter, more or less significant, than its duration in seconds might suggest.

National Symphony Orchestra: Haigh, Buckley and Dennehy

Friday’s orchestral concert was given to three premieres. The first was the Irish premiere of Robin Haigh’s SLEEPTALKER (2021), in which Leroy Anderson-esque whimsy was juxtaposed against thicker, softer chords like dreams against sleep. David Brophy and the NSO had consummate control over the work’s elastic tempo and difficult timbral contrasts, but Haigh didn’t quite bring his contrasting elements to synthesis: it was attempted at the climax but felt unearned.

The other Irish premiere was Donnacha Dennehy’s 2020 violin concerto. This is an excellent (if somewhat disjointed) work, especially the first movement, but Dennehy was outshone by Stephen Waarts, who dispatched the relentlessly virtuosic part with cool command in an astonishing performance.

Bookended by these two works was the world premiere of Linda Buckley’s Tuile agus Trá, in which the NSO was joined by Iarla Ó Lionáird. Unusually for Buckley, this was a purely acoustic work. Her orchestral writing here did not have the individuality of colour of her electronic writing, but the wide swells of this music were effective nevertheless. Perhaps, indeed, the simple but warm scoring was just what was needed to unobtrusively support Ó Lionáird’s singularly colourful sean-nós singing. Ó Lionáird was slightly amplified, and the effect of this was so great that I wonder if the work really is purely acoustic: the amplification disembodied his voice, made it ghostly – apt for this personal and vulnerable work written in memory of Buckley’s mother.

Iarla Ó Lionáird with the NSO performing Linda Buckley’s Tuile agus Trá (Photo: Molly Keane)

The Archetypes Project

Nathan Sherman and Alex Petcu devised The Archetypes Project to commission works on the collective unconscious, and they brought several of these works together in a concert from the dry ice-filled, strobe-lit Diatribe Stage. Due to a mistake on my part, I missed Nick Roth’s Sophia × Bythos and the world premiere of Ann Cleare’s gravity dreams iv – my apologies to the composers.

The first piece I did see was the Irish premiere of Siobhán Cleary’s Scheherazade: The Art of the Trickster (2023). I found it unsatisfying, with too many gestures (such as forte sawing on the viola) that needed more musical preparation to be effective – it was as if the work was all climax.

There followed Benjamin Dwyer’s Laganton (2024), an emotionally complex work about a small indigenous community in an Oceanic island called Latangai whose leader lent Dwyer’s work his name. We know of Laganton through the field work of artist–anthropologist Glennie Köhnke in the 1970s. Since then, he has passed on, his son has emigrated leaving the community to dissipate, and Köhnke, a friend of Dwyer, suffered a major stroke. Dwyer feels keenly this fraying of Latangai’s culture, and Laganton is an attempt to celebrate it and even extend its life through its transformation into this colourful work full of surprising sounds.

The concert ended with Sherman’s Cauldron of Morning (2024), in which Sherman and Petcu were joined by Garrett Sholdice on keyboard. This was the most theatrical work in a theatrical set, with strobe lights aggressively used at a crucial point of sudden silence that was all the more striking for the intensity of the noise that preceded and followed it. But for all that this music was built on heavy distortion and volume, it was acutely heard, and exquisite music to nuzzle your ears into.

AWAY

Friday’s final concert was a set by Diamanda La Berge Dramm and her mother, Anne La Berge. It is hard to describe this set. The least bad term I came up with is ‘postmodern variety show’, which I intend as a compliment. The set was heavily indebted to the playful wrongfooting of contemporary European theatre, with liberal use of mixed media (such as video) as well as a free way with the distinction between actor and character, performance and rehearsal, and what performers say to each other behind the scenes and what they declaim to the audience. But in amidst this were some songs from La Berge Dramm’s 2022 Chimp (which she wrote while composer-in-residence with Crash) that were not just elements in a piece of theatre but there for their own sake.

At one point, La Berge Dramm interrupted proceedings to ask La Berge ‘what do you like most about having a body?’ The question stuck with me: surely that’s a wild thing to ask one’s mother? Or is that just me? It’s so wild that surely this line is there to establish that the voices we’re hearing are characters, not La Berge Dramm and La Berge themselves – unless it’s not? And if it is indeed one character asking another character something, does that mean that it is less honestly answered?

AWAY was replete with such arresting moments, stitched together by charming storytelling, touching songs and charismatic performances – or people. As with much of La Berge Dramm’s work, it was a great lesson in how varied contemporary music can be without losing its edge.

Anne La Berge and Diamanda La Berge Dramm (Photo: Molly Keane)

Trumpets!

Taking the festival out of the National Concert Hall on Saturday was a free lunchtime concert in the courtyard of Dublin Castle for massed brass: thirty-six trumpets all told, gathered from across Europe, and I spotted a handful of trombones and tubas too. The centrepiece of this concert was the world premiere of a new work by Austrian composer Peter Jakober, Little Beauty. In this piece, in which the musicians were arrayed around the courtyard playing roughly the same music but to click tracks that all differed from one another by a few beats per minute. The effect was quite wonderful: at any given point in the courtyard, you heard sufficiently few of the instruments that they combined to create one sort of overall sound, but as you walked around, that ‘whole’ gave way to very different wholes. This was all intensified by the echoing of the courtyard, which is surrounded by buildings on all sides, creating a great sonorous sound in which plenty of interesting detail could also be found.

The Dancers Inherit the Party

Chamber Choir Ireland’s annual contribution took a while to find its feet. It contained two world premieres. The first, I am, by the Irish composer Eoghan Desmond, was a meditation on the Holy Spirit. Desmond knows his forces well, but this was an extremely conservative work – not just harmonically, but in its textural homogeneity and overuse of warm colours and mouth shapes.

The second and much larger premiere was Gabriel Jackson’s The Dancers Inherit the Party. This was a striking setting of several of Ian Hamilton Finlay’s poems interspersed with settings of his ‘concrete poem’ ‘EVEN- / ING / WILL / COME // THEY / WILL / SEW / THE / BLUE / SAIL.’ This work is a stylistic smorgasbord: some of the settings are for solo singers, others use complex hocket-like devices. Jackson did a great job of capturing the uneasy wit and emotional range of Finlay’s poetry, and not only by intensifying the emotion of a given line: the settings are intelligent and rarely obvious, with the sad undercurrent brought out of lines that could more naively be read as jocular.

A slightly less new work was The City, Full of People by Cassandra Miller, which CCI premiered at Louth last summer. I had heard this piece on record, and had liked it fine, but hearing it live was an entirely different experience: the choir is divided into six groups that are spread around the church like little islands, affectingly representing non-believers’ shared but disconnected search for a spiritual life.

Around Here, the Birds Plant the Trees

Natalia Beylis’ Around Here, the Birds Plant the Trees (2023) was co-commissioned by NMD and Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival, where it received its world premiere last November. It was written collaboratively with Willie Stewart (percussion), Eimear Reidy (cello), Tola Custy (fiddle) and Ailbhe Nic Oireachtaigh (viola), with Beylis on electronics and assorted objects relevant to the work’s themes of ‘land and its borders, guardianship, governance and policy – and how this all affects the inhabitants’: a bird-spotting guide, pebbles, horse chestnuts and so on. It opened with some rather conventional free improvisation, finding its voice with Stewart’s open and charismatic solo, and culminating in an extended ‘spiral’ of an endlessly repeated folk melody that would not have been out of place on a Lankum record. It did not seem to me that this performance came together, but the setup of the room could have been at fault here: sitting at the back of the Kevin Barry Room, I could not see the performers, and could only wonder, investigating the stage afterwards, what the wooden birds and seashells were all about.

A Prayer to the Dynamo / A Winged Victory for the Sullen

The NSO returned to the main hall on Saturday night to give the Irish premiere of Icelandic ambient composer Jóhann Jóhannson’s A Prayer to the Dynamo (2012), this time under the baton of Daníel Bjarnason. Jóhannson’s minimalism is all about softness and warmth, and Bjarnason conducted with great sensitivity, allowing the brass swells to wash over the strings without overwhelming them.

The second half of this concert was connected to the first only by also being ambient music, so we returned after the extended interval to see the stage totally refigured to accommodate just the electronics, piano and guitar of A Winged Victory for the Sullen (Adam Bryanbaum Wiltzie and Dustin O’Halloran) as well as a small chamber ensemble (frustratingly uncredited, apart from briefly by Wiltzie from the stage). This set, which consisted of songs from the duo’s back catalogue, was all about volume: huge soundscapes of sophisticated textures wash over the audience, with the lowest notes pulsating at the cusp of hearing. This is music as massage, using hugeness of sound to physically, directly affect one. Perhaps I shouldn’t, but I resist this kind of thing violently, and I found my mind wandering inconclusively on thoughts such as whether a new-music festival that contains this music as well as Gerald Barry and Diamanda La Berge Dramm is broad or incoherent.

Bekah Simms’ Cryptid

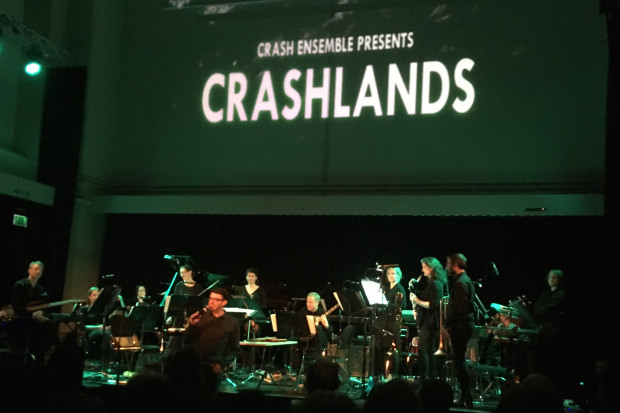

The final concert of the day was another Crash gig. It opened with the Irish premiere of Antti Auvinen’s Boundary Bourrée (2024). This was an intense, tense work of sharp, dry textures. It was roughly divided into three, concise attacca movements and was in every sense brilliant.

It was followed by the world premiere of Bekah Simms’ half-hour Cryptid, which she wrote while composer-in-residence at Crash. This was another highlight of the festival. Simms created this piece in close collaboration with Crash, asking each player to provide basic compositional material in the form of sounds and gestures they were drawn to. These sounds were then turned into, on the one hand, scores from which the players would perform the finished piece, and on the other, a tape part of modulated, distorted iterations. The interplay between these two sound sources was much of the engine of the work. Where a sound came from was often obscured; this created some uncanny moments when the performers seemed to be playing impossibly complex polyrhythms, and led to some startling ‘reveals’ when, for instance, we were reminded that we were listening to the slightly detuned tape piano by a big entry from the live piano.

Cryptid is an infinitely precise and detailed work in which slight changes carried great emotional weight. Given this, it was just a little disappointing when it ended by moving to an unprecedentedly warm place – it was a nicely executed opening up of the sound, but the music beforehand had so much soft, wintery beauty that this turn to a more familiar beauty felt like a regression rather than a deliverance.

Crash Ensemble performing Cryptid by Bekah Simms. (Photo: Molly Keane)

Closing thoughts

As ever, I was glad to have caught so much of New Music Dublin, and the healthy audiences at almost every concert indicated that festival director John Harris is doing an admirable job of spreading the word of new music. But I also left feeling that the two days amounted to less than the sum of their parts. When looking through my tickets to see what gig was up next and seeing that it was, yet again, Crash Ensemble or some novel combination of its members, I felt just the slightest disappointment. That feeling is not fair to the consistently excellent Crash, who introduced me to a lot of great music this year as every other year. But New Music Dublin is increasingly stuck in a rut, with familiar composers and performers showing up again and again to the exclusion of international and even other Irish musicians. I hope next year’s festival will not just be excellent but also surprising.

For a review of days 1 and 4, see here.

Subscribe to our newsletter.

Published on 1 May 2024

James Camien McGuiggan studied music in Maynooth University and has a PhD in the philosophy of art from the University of Southampton. He is currently an independent scholar.