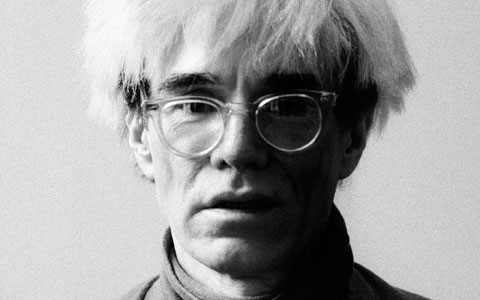

‘Good business is the best art’ – Andy Warhol

The Art of Money

How are arts organisations and artists going to get through this recession? This is hardly an ideal time to ask this; the right time was a couple of years before it happened. Nonetheless, as budgets continue to disintegrate, we have to start seriously discussing the funding of artists and arts organisations, and how we are going protect it – what’s left of it.

In the arts, we often cite lateral thinking as one of the benefits of arts involvement, but how much lateral thinking on the economics of the arts has come from the arts sector? Traditionally, we have credited arts organisations with the skill of making a lot happen with little money, but we acknowledge that that is because nobody gets paid that much. When the budgets of organisations begin to grow – and usually it is as a result of a bigger grant rather than more sales – that funding usually goes into paying people a little better for what they formerly did for very little. Most artists and arts entrepreneurs would accept that if they had put the same amount of effort into anything else apart from the arts, they would probably have become very wealthy.

It is this thinking on the economics of the arts that we have to start questioning. How is that we have so many people of energy, ideas, creativity and intelligence in the arts, and yet they haven’t even begun to generate enough money to support what they do. Millions upon millions are invested into the arts, yet arts organisations are in the same situation annually: broke, struggling, unable to commit, unable to plan, and relying heavily on what the next move of their arts council will be. How have we not managed to break this cycle? Something is missing. Some connection is not being made.

We are very good in the arts community at sharing our work – that is what we spend most of our time doing, removing as many of the barriers as possible to people experiencing the art that we produce and present. Rarely, however, do we share what we are learning along the way, such as the entrepreneurial skills which we are all the time developing. Neither do we share information, be it about audiences, readerships or communities; finance, industry or technology; or planning, costing and scheduling. The vast majority of those in the arts are in the rare situation of feeding off one single financial source, usually an arts council, yet they are not working together on any significant level to pool their knowledge and experience. The result is the current situation with the arts – chronic funding problems.

Can we use our collective entrepreneurial skills and business sense to change this? The conventional thinking on the relationship between the arts and business is that it inevitably leads to compromise for the former. Arts communities, however, have many successful people who manage to outwit that, striking a balance between business acumen and cultural concern, between artistic ambition and financial prudence, between the language of cultural entrepreneurialism and the language of commercial business. We don’t hear much about them; what they know cannot be found in books; and it won’t be issued as a memo by any commercial business. It is only learned through having formative experiences in the arts, and then being compelled to develop business skills tailored to that unique world.

On the books of every arts council from Ireland to New Zealand, from Finland to every state in the US, are these kinds of people – arts entrepreneurs (artists, most of them) who have learned to be successful by balancing the demands of both the arts and business. Over decades, they develop relationships with arts councils, they learn how to make maximum use of that funding, how to leverage financial support from other areas, how to grow their projects, organisations or companies, creating jobs, creating indirect employment, generating cultural activity in forgotten corners of the country, providing inspiration, education and experience for those who may go even further. Yet they never garner consideration as great entrepreneurs because financial profit is rarely the result of their endeavours.

We are awash with these people and we need to start tapping them for their ideas, pool their trove of experience and skills, and break the cycle of a chronic lack of funding of the arts.

Here is a way in which we could start doing that: each time a new arts council-funded music venture is started, be it a concert, recording or festival, it is likely that those new in the game will have to go through an elaborate learning experience, something almost identical to what many others before them have experienced – audiences, production, budgets, personnel, publicity and any number of other things. Arts councils do not offer entrepreneurial skills, but they do have access to experienced entrepreneurs who have those skills in abundance, people who have learned to make space for their artistic ideals using the tools of business. It makes sense for arts councils to offer individuals and groups starting out the advice of those who could not only help them avoid some of the usual pitfalls, but actually develop something truly sustainable. The same principal could be applied for each newly-formed theatre company, gallery, artist collective, opera production or publishing company.

In time, with such a ‘mentoring’ system, we would build up much tighter-knitted arts communities, with the new blood coming in able to build on what has been done before, rather than starting from scratch every time. The result will be less opportunities missed, less mistakes made, and, consequently, more money to go around.

Published on 1 June 2009

Toner Quinn is Editor of the Journal of Music. His new book, What Ireland Can Teach the World About Music, is available here. Toner will be giving a lecture exploring some of the ideas in the book on Saturday 11 May 2024 at 3pm at Farmleigh House in Dublin. For booking, visit https://bit.ly/3x2yCL8.