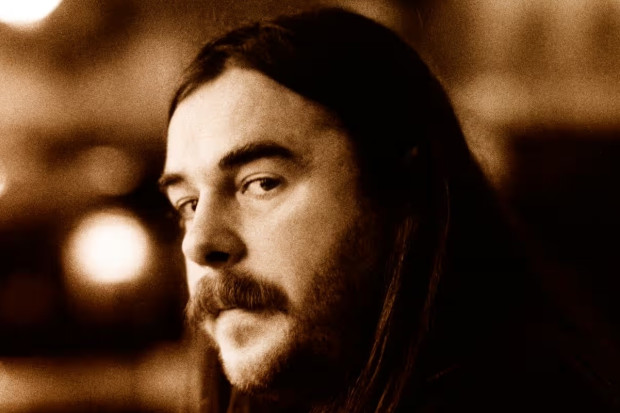

Artwork for Seán Clancy's new album.

Revealing the Thinking Behind the Music: Seán Clancy's 'Four Sections of Music Unequally Divided'

Four Sections of Music Unequally Divided, like much of composer Seán Clancy’s recent work, is music in which simplicity belies depth. You can simply listen to it and be massaged by its resonant gamelan notes and piano tremolos embedded in a rich cushion of electronica. Or you can listen to it while following the score, which is easily done when Clancy provides it in its entirety in the booklet (it comfortably fits on a single page). The peculiar compositional method of the piece now becomes clear: it consists of musical cells of indeterminate length loosely arranged on the page into four sections. But it is only when you read Clancy’s liner notes that the depth of the music reveals itself: he draws close around him his influences, charting how Four Sections has been inspired by the conceptual artist Sol LeWitt and the composer and music theorist James Tenney (the work’s dedicatees), among others. The notes also show how Four Sections, despite its length (44 minutes in this performance), is but one take on some concerns that Clancy has been exploring for some time.

A description of the piece is needed first. Composed in 2018, the score is very thin in its directions: it is for any number of performers, and its four sections can be played in any order or simultaneously. The present performance is for gamelan, synthesisers and piano, all played by Clancy himself, and the composer here performs the sections consecutively and in order. Each section consists of a number of short musical cells, sometimes single breves. Almost the entire piece is restricted to the pitches D, E-flat, A and B-flat.

This restricted palette allows Clancy to focus on the difference that reveals itself through stasis, one of the main concerns of this work. This has been a recurring theme for the composer: in 2022’s Peso, thirteen oscillators sound for an hour, the performer adjusting their relative volume not to change the notes but to foreground the different harmonic relationships that are already there. The stasis of Four Sections is the repetition of its notes and cells; the single chord that comprises ‘Section IIIB’ swells, unaccompanied, from pianissimo to fortissimo and back again for thirteen minutes. Each swell is inevitably different, and the chord, which is an unmeasured tremolo played between the hands, never has a settled sonority as Clancy plays at the limits of his ability to control the instrument. This is intentional: Clancy gives credit to Tenney for inspiring him to write this way. It is a lovely chord too, voiced in stacked thirds and sixths that combine to create more dissonant intervals – it seems designed to allow the listener to either enjoy its warmth or attend to its ever-shifting harmonic character, as per their desire.

Influences and inspiration

Tenney is more than an inspiration: the score for the final section of this work is almost identical to – Clancy says ‘a transcription (or whatever you want to call it) of’ – Tenney’s 1972 one-note composition Having Never Written a Note for Percussion. Four Sections also pays homage to Tenney’s theoretical writings. To give one example, Tenney developed a ‘gestalt theory’ of music in which he articulated the way in which we break musical time into distinct sound events (such as a note or a melody) rather than hear it as a continuous stream. The neat structure of Four Sections highlights, perhaps, the ‘levels’ of what Tenney calls temporal gestalt units: the shortest units of Four Sections (elements and ‘clangs’) fit tidily under the larger ones, and things are repeated as if to allow us to better study them.

What Four Pieces owes to LeWitt is – among other things – the freedom to let a single idea run its course. Clancy, quoting LeWitt’s ‘Paragraphs on Conceptual Art,’ calls the idea behind Four Pieces a ‘machine that makes the work.’ Thinking of things this way, which enjoins the composer to avoid admixture of the idea with ‘caprice, taste and other whimsies,’ gives Four Pieces a fine clarity. It also licenses Clancy making such an extended work from such little material.

Listeners who do not consider it terribly important what LeWitt’s reflections license or who don’t think that they should need to know what Tenneyian clangs are in order to listen to music might wonder whether Clancy is one of those artists who wield their erudition like a shield or weapon, as if a good theoretical justification for their work can expiate musical shortcomings or compel the listener to acknowledge that the music is good. The way Clancy draws in the thinking behind his music could not be further from this. The sense one gets is rather that he is surrounding himself with friends, or wanting to give the listener as much context and understanding as possible. It’s even self-effacing, as if he wants you to see his music not as a miracle of genius but as just one contribution to a community. As such, the invitation to turn one’s attention to the theoretical and musical background and influences to Four Pieces is a warm one – a warmth that permeates this soft work.

Seán Clancy’s Four Sections of Music Unequally Divided is released on the Birmingham Record Company label. To purchase the digital album, visit https://seanclancy.bandcamp.com.

Subscribe to our newsletter here.

Published on 26 April 2024

James Camien McGuiggan studied music in Maynooth University and has a PhD in the philosophy of art from the University of Southampton. He is currently an independent scholar.