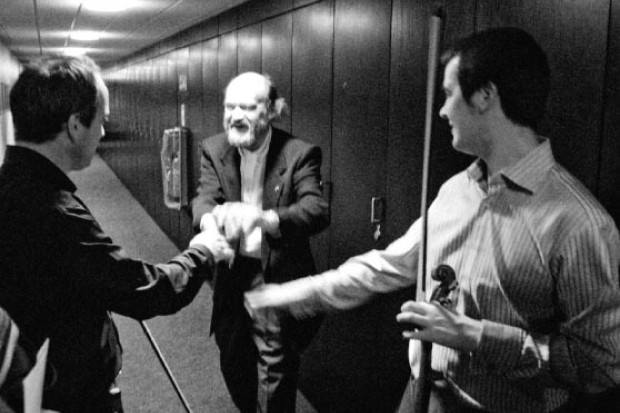

Ciarán Crilly conducting the RTÉ Concert Orchestra and Resurgam (Photo: Cécile Chemin)

Smaller Voices of the Irish Civil War

In introducing her new cantata, Who’d Ever Think It Would Come To This?, Anne-Marie O’Farrell made reference to ‘Amhrán na Leabhar’, the Song of the Books, in which the nineteenth-century poet Tomás Rua Ó Súilleabháin laments the loss of his treasured books after the ship on which they were being transported sank. Drawing a clear analogy, she spoke of ‘the drowning of wisdom that goes on in war.’ And the subject of the cantata is war; written in commemoration of the Irish Civil War, with a libretto built from letters, reports and other documents from the time, drawn from the UCD Archives. To this, the librettist – noted war correspondent Ed Vulliamy – added of the aftermath of war, quoting Coleridge, ‘A sadder and a wiser man,/ He rose the morrow morn.’ These two sides of wisdom suggest an ambitious work, one which seeks unflinchingly to explore the horror of war.

The 65-minute cantata – an orchestral work following her Eitilt at New Music Dublin last year – was premiered last Friday night, the 30th of September, at O’Reilly Hall in UCD, with soprano Colette Delahunt, mezzo-soprano Sharon Carty, tenor Dean Power and baritone Rory Musgrave as soloists, each performing various roles. Supporting them were the RTÉ Concert Orchestra, conducted by Ciarán Crilly, and the choir Resurgam. The work is in seven more-or-less chronological, more-or-less continuous parts, from just before the Civil War to its conclusion, and Vulliamy’s libretto skilfully creates a narrative arc while the words still maintain the feeling of text glimpsed while scanning archival documents.

Canny orchestration

Most striking of all to the experience – and a sensation which will be lost in the forthcoming broadcast on Lyric FM (14 October) – was the sense of space during the performance. It’s been a long time since I last heard an ensemble the size of the RTÉ Concert Orchestra performing on the same level as the audience; not up on a stage or down in a pit. Combined with the very open, clear acoustic of O’Reilly Hall and the composer’s canny orchestration, the direction from which sounds originated was often as surprising and as integral as the sounds themselves. In near silence, a percussionist walked in a circle around the audience, scraping sandpaper. To the left, the harp dominated in some dramatic passages (unsurprisingly as O’Farrell is a harpist), the performer Geraldine O’Doherty scratching the strings with her fingernails or hammering on them with spoons. The whole string section took up sheets of paper, tapping on them in unison with their fingers.

Of course, the orchestration wasn’t just the use of novel sounds; O’Farrell writes skilfully for the whole ensemble. Flourishes in percussion that enhance or unsettle a still chord; a ghostly tin whistle or uilleann pipe passage floating up from the centre of the orchestra. (It is a credit to the composer – and to the performer Mark Redmond – that these instruments, which often rub somewhat uncomfortably against the orchestra at large, felt utterly integrated.) The influence of film composers could be felt at times – bright brass chords in the vein of John Williams, or a motoric, almost jaunty passage for strings that evoked Bernard Herrmann. That latter passage is given a grim irony as the chorus sang of a brutal assault, ‘Tied him to the tail end of a motor car, / And pulled him behind for 3 miles.’

Smaller voices

Some broader sections of the cantata struck deep. The music consciously avoided, as much as possible, the words of prominent figures in the Civil War, focusing on what UCD Principal Archivist Kate Manning, who conceived the project, called ‘smaller voices’. In the powerful fifth section, we hear the letters of Erskine Childers, the English-born Republican sung mostly by Rory Musgrave, and those of his wife Molly, performed by Sharon Carty, as they experience the agonising wait for his execution.

And it is no surprise that such a work, coming to the end of war on the words ‘it’ll be dawn soon’, should end on a major chord, but its arrival nonetheless feels both satisfying and appropriate. In the closing seconds, O’Farrell weaves in a small, clear motif on the tin whistle, a tinge of bitterness in the bright dawn.

The performers were on fine form, with the orchestra sounding full and clear, and the soloists filling the hall with ease. Musgrave’s voice in particular burned dark and strong on every entry. Carty and Delahunt sang with deep pathos, and Power sometimes with an excellent sense of professional detachment, most notably and disconcertingly on the words ‘they mean to shoot him.’ Resurgam also sang well, though unfortunately the acoustic in the hall – very effective in some ways – often muddied their words when the whole ensemble sang together.

Whether the audience left the hall sadder and wiser, as Vulliamy hoped, I can’t say, but they received the work warmly and positively. And it was Vulliamy’s phrase, something he said during the opening talk, that stayed with me during and after the performance, ringing through the bittersweet final notes and at the heart of the work. He described the ‘macabre intimacy’ of wars like the Irish Civil War. ‘The people knew the people they were killing.’

Visit https://civilwarcantata.ie/

Subscribe to our newsletter.

Published on 6 October 2022

Brendan Finan is a teacher and writer. Visit www.brendanfinan.net.