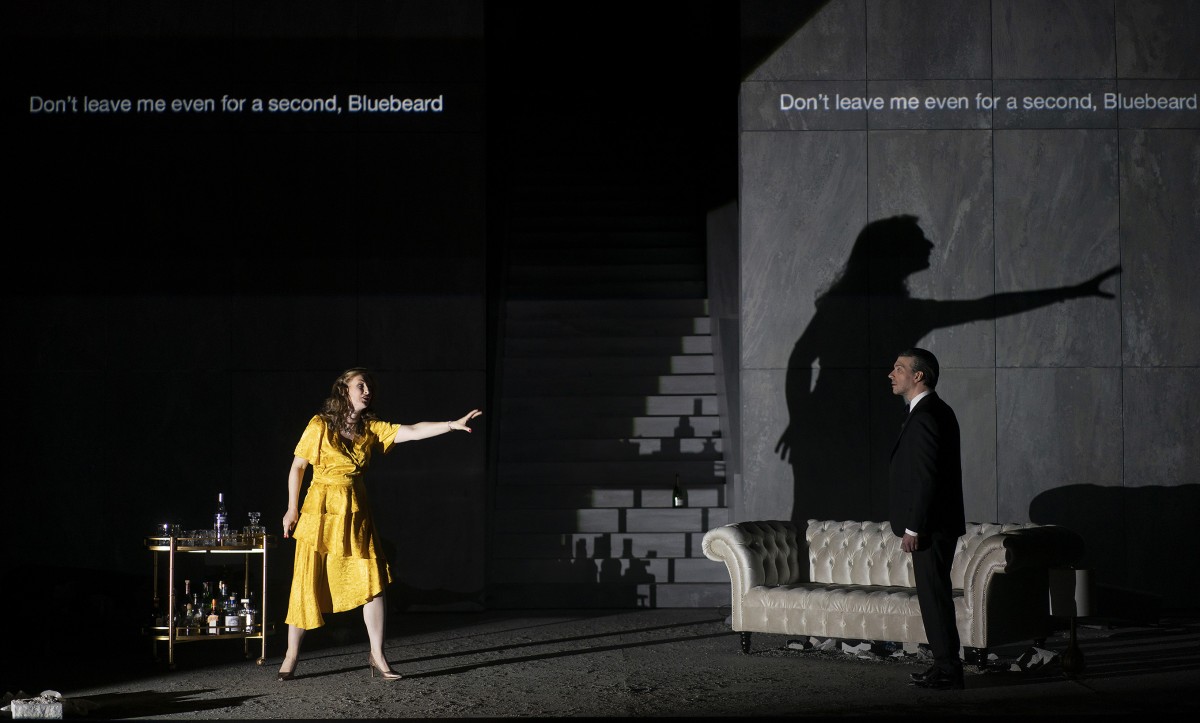

Joshua Bloom and Paula Murrihy in ‘Bluebeard’s Castle’ (Photo: Pat Redmond)

Not Your Ordinary Megalomaniacal Psycho

Exactly a century after its premiere at the Royal Opera House in Budapest, Bluebeard’s Castle, Bartók’s one and only opera, had its Irish staged premiere in the more modest surroundings of the Gaiety Theatre as part of the Dublin Theatre Festival. The opera’s short duration, lasting barely over an hour, makes it a frequent choice to form one part of a double-bill and Irish National Opera’s decision to let it fly solo may have had some punters wondering whether they would get the full bang for their buck. However such concerns were swiftly set aside in what turned out to be one of the operatic highlights of recent years.

In his reworking of the Bluebeard folk tale, Bartók’s librettist Béla Balázs intensified the story’s darker aspects making it into an allegory of obsession, love’s delusive power and the immutability of human nature. Against her family’s wishes, Judith enters Bluebeard’s Castle as his wife despite being well aware of his murderous past and the fate that has befallen those who have threaded this path before her. Convinced that she can change him through her unwavering devotion, she proceeds to open the doors of the castle to illuminate the darkest corners of Bluebeard’s inner world. There are seven doors in all and as they are unlocked one after another, the full horror of Bluebeard’s dominion is gradually revealed. Giving expression to this grim scenario is Bartók’s sensuously colourful score which alternates between rich, luminous writing and dissonant effects that have long since become the stock-in-trade of Hollywood film composers.

Revealing an inner world

The omens that this was not going to be a conventional retelling of the Bluebeard myth were present right from the beginning. Director Enda Walsh and stage designer Jamie Vartan created a set that resembled a Gotham city style bunker of concrete and rubble. There were some minimal but glitzy furnishings – a drinks trolley, some lamps and a sofa – which stood out from the otherwise austere surroundings. A boy (Elijah O’Sullivan) appeared on stage and seemed to spend an eternity assembling a battered speaker. When done, he delivered the ambiguous prologue in Walsh’s English translation before finishing with a few lines from the Hungarian original. Where was all this leading, one wondered?

The opening of the first five doors proceeded along more predictable lines. The film noir theme was extended to both of the characters who entered as if arriving home from a societal ball with a debonair Bluebeard (Joshua Bloom) in his dinner jacket and Judith (Paula Murrihy), as his dame, in a bright yellow dress. The latter, intoxicated by a belief in her own powers of loving persuasion, continually probed the reticent Bluebeard who was loath to reveal his inner world. The handwringing that this entailed was nicely choreographed with Bloom’s slow brooding movements set against the more restless Murrihy. As the prescribed directions in the score are so minimal, this constant movement effectively offset the visual stasis that can so easily result with this particular opera if the singers are allowed revert to singing statue mode. Credit must also go to lighting designer Adam Silverman and video designer Jack Phelan who captured the progression from the darkness of the opening to the dazzling brightness of the fifth door through projections on the concrete wall and the creative use of a disco ball.

Photo: Pat Redmond

Pressure gauge

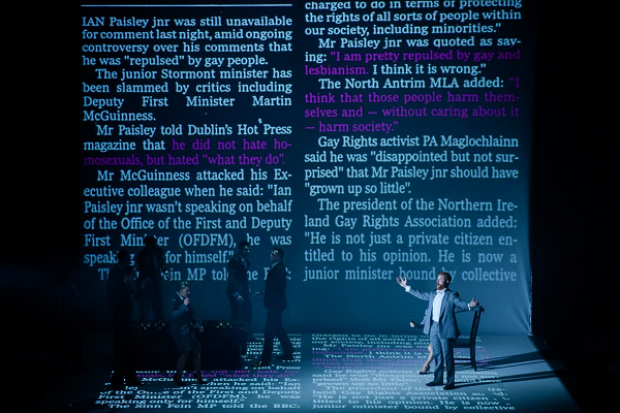

Aside from the curious treatment of the prologue, however, by this point in the story it was a case of so far, so conventional. It wasn’t until the penultimate sixth door, which opened on to the lake of tears, that the production really came into its own. Pressed by Judith as to the fate of his previous wives, Bluebeard flung his glass at the wall and proceeded to beat himself repeatedly on the ground in an apparent act of self-hatred. As the tears of the lake swelled in the background like a pressure gauge, this graphic escalation in tension prepared the way for the big reveal when Judith opened the seventh door revealing Bluebeard’s wives, presented here as if they had been collecting dust in his cellar since the era of Louis XVI. They shuffled out, ostensibly to usher Judith to join them in sharing a similar fate. Except that this is not what actually transpired.

As Judith was being fitted with a matching dress by the wives, the backdrop lifted to reveal a group of about twenty children wearing bright multi-coloured clothing dotted about the stage in the manner of an advertisement for Benetton kids. Their grim demeanor and zombie-like poses made for a surreal scene amidst even more rubble with the stage now resembling the aftermath of a war-zone. The boy from the prologue reappeared, joined hands with Bluebeard and they both descended down a stairs at the back leaving a shell-shocked Judith alone out front. Both herself and the audience had been deceived all along.

Upending the plot

While this functioned as a stunning dramatic climax to the opera, it put an entirely new spin on the notion of Bluebeard as just your ordinary, decent, megalomaniacal psycho. The idea that he has gone through several wives simply to surround himself with more children heaps more layers – and rather disturbing ones at that – on an already complex character. In the final moments of this production, we were left in no doubt that it was he who was ultimately victorious: his wicked grin radiated a sense of cunning superiority as Judith slumped on the sofa, utterly defeated. Unlike many ‘postmodern’ upendings of the traditional plot, which often seem heavy-handed, this one was well earned. The whole point of the interminable fuss with the boy and his speaker at the beginning became clear and we were left with even more unsettling questions than could have been anticipated.

Photo: Pat Redmond

Powerful and affecting

Throughout the opera, conductor André de Ridder and the RTÉ Concert Orchestra did a first-rate job of realising Bartók’s magnificent score. The Gaiety’s tiny pit and bone-dry acoustics – good for theatre, bad for opera – tend to make orchestras under less incisive direction sound as if they are playing inside one of Bluebeard’s padded cells. But de Ridder managed to overcome these obstacles by superb balancing and skilful coordination of the musicians, some of whom were placed in an alcove to the side of the stage in order to circumvent the spatial limitations.

The final credit must go to the singers however. Joshua Bloom’s transformation from a well-groomed man-about-town to something far more sinister was thoroughly convincing while Paula Murrihy extracted the audience’s sympathies beautifully as Bluebeard’s ill-fated bride. The singing throughout was powerful and affecting with both singers negotiating the difficult speech rhythms of Balázs’ Hungarian libretto with apparent ease.

This production was the complete package and if INO can replicate last weekend’s success with similar, off-beat repertoire they may well stake out a name for themselves beyond the limited confines of the Irish opera circuit.

Published on 18 October 2018

Adrian Smith is Lecturer in Musicology at TU Dublin Conservatoire.