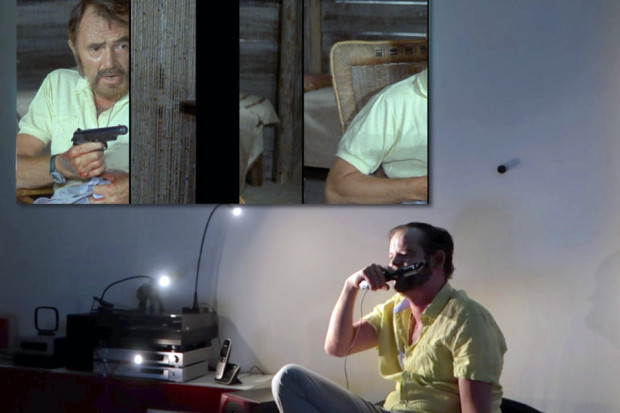

Zubin Kanga performing on the opening night of Music Current last week (Photo: Mihah Cucu)

Electric Performance

There was something intensely comforting about sitting in a dark, quiet room, surrounded by the dim shapes of strangers, watching a performer wrestle with technical problems. The sensation was more than just the excitement at being back at long-postponed concerts; it seemed entirely consistent with both pianist-composer Zubin Kanga and Dublin Sound Lab’s approach to working with performance with electronics – coolly relaxed, hands-on and transparent. For Kanga, electronics are clearly not an addition, but a fundamental part of working with his instrument, and the physicality of his performance a keystone rather than an afterthought. This programme saw him performing complex musical textures, bending over the piano strings armed with e-bows, speaking, and performing physical actions like pretending to sleep and clanking a spade.

The programme kicked off with Alexander Schubert’s WIKI-PIANO.NET. This is a kind of crowd-sourced collage work accessed via a website that can be edited by anyone, and performed ‘as is’ at the moment of performance. It moves quickly through fragments of written piano scores, text – ‘pogonophobia: fear of beards!’ – instructions for actions, electronic sounds, even videos of Kanga himself in previous performances. It produced a kind of unpredictable whimsy while maintaining an inexplicable wholeness. One of the most interesting things about the piece was not only its aleatoric nature, but the way it weaved its own programme note into its texture, including reflections by the performer, where Kanga discussed his own experience with the piece – including noting that this was the first of his performances that encountered technical difficulties. (At the time of writing there is still evidence of this technical mishap, in the text that appears in the introduction: ‘I still think this pause and reset was all part of the piece’).

Fergal Dowling’s Fake Piano was one of three works to receive its world premiere as part of the programme, alongside works by Michael Finnissy and Nicole Lizée (the other pieces, by Schubert and Scott McLaughlin received their Irish premiere). Fake Piano is a piece that explores directly the relationship between live performance and electronics; based on the Antescofo system developed by IRCAM, a programmed digital pianist ‘listens’ to the live performance and responds to what it hears. The result is not so much a ‘fake’ piano as a ‘ghost’, the counterpoint to the complex flurries written by Dowling sounding so naturally and realistically responsive. Fake Piano was followed by McLaughlin’s evocatively titled In the unknown, there is already a script for transcendence, a standout in the programme both thanks to its complete shift in approach to material, creating a moment of absorption in sound, and for giving Kanga a chance to really shine through his simple but expressive physical performance. For this piece the strings of the piano were prepared (again taking a few moments that disrupted the flow of the performance not at all, thanks to Kanga’s comfort on stage), then played with e-bows, creating uncanny bells and evolving metallic hums that played beautifully against the few struck piano notes.

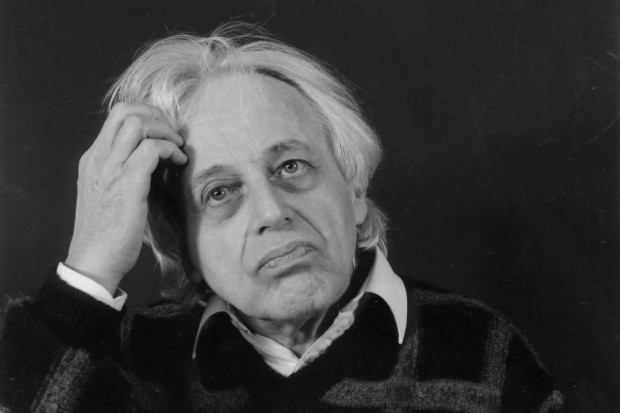

The final two works of the programme were both works with video components, though which make use of the medium in almost polar opposite approaches. Finnissy’s Hammerklavier (Part 2) with video by Adam de la Cour is a moving, sober reflection on the suppressed and secretive lives of queer people in the 50s and 60s, including that of the pianist Sviatoslav Richter. Finnissy’s music reworked movements of Beethoven’s ‘Hammerklavier’, teasing threads apart and weaving them anew, just as de la Cour did with his material, fleeting fragments of bodies and movement.

Lizée’s Scorsese Études (part of her ‘Criterion Collection’) was much more playful, not so much breaking apart and reworking her material – tiny fragments from significant movies by the director – but reducing it to the essence of an aural and visual gesture, looping it before handing it to the piano part to be rebuilt. We encounter a motif created from a momentary tumult of sound in the climactic scene of Taxi Driver, an accelerating rhythm from Matthew McConaughey’s chant in The Wolf of Wall Street, plus the composer’s physical interventions with her own hand through paper animations. It was in this piece that a spade and bucket formed a part, with Kanga not just responding to, but almost taking part in a pivotal scene from Goodfellas.

It is because of Kanga’s assuredness not just as a pianist but as a performer of sound and action that this programme worked so well as a whole, an ideal start to a festival presented by Dublin Sound Lab, who continue to present themselves as real innovators in new music in the city.

Read a review of the final night here. For more on Music Current, visit www.musiccurrent.ie.

Published on 18 November 2021

Anna Murray is a composer and writer. Her website is www.annamurraymusic.com.