Narolane – MuRli, Denise Chaila and God Knows

The Story of a City

Out of Place approaches Féile na Gréine’s ambitions as a festival but through another means: the lens of cinema. Since 2018, the festival has been running as a volunteer-led DIY organisation that spotlights Limerick city’s thriving music scene. Whereas the festival is temporary by nature, it is also active in creating a lasting community around the music; as a documentary, Out of Place takes these efforts further by bringing the focus to the musicians when faced with the 2020 lockdown, on top of already limited options for performance.

The film, which was nominated for Best Documentary at the Irish Film Festival in London last year, is directed by Graham Patterson, produced in collaboration with Hugh Heffernan, Jack Brolly and Diarmuid O’Shea, and features an original score by Mícheál Keating alongside the music of the artists it portrays. It takes the opportunity of the pandemic-induced lockdown as a moment for reflection and is made up of recordings of rehearsals, recording sessions, performances, and interviews with the artists behind four music groups from the city.

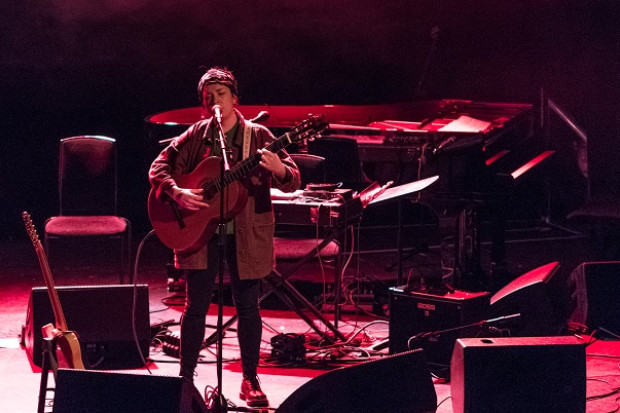

Setting out their agenda with the subtitle ‘music community defiance’, it profiles a diverse range of artists who are from, living and working in Limerick, including Denise Chaila, God Knows and MuRli – founders of the hip hop label Narolane; John Ahern and his indie-folk band Hey Rusty; Aisling O’Connor, James Reidy, Laya Meadhbh Kenny and Cian McGuirk who together form the new-wave inspired guitar outfit His Father’s Voice; and Pádraig O’Donoghue, who performs protest music and poetic gabber with a band under the pseudonym Post Punk Podge and the Technohippies.

Act of defiance

Out of Place opens with a close-up of portrait photography being developed, before launching into His Father’s Voice rehearsing in a practice room. Their singer and guitarist, Aisling O’Connor, shares her experience: ‘It’s an act of defiance to create regardless of the opportunities that are around you’. The scene cuts to a black-and-white montage of live performances. We’re informed that it is 2020. We hear an interview with Narolane before they take to the empty streets to record a God Knows freestyle verse. Although the interviews in the film speak about the lack of spaces and opportunities more generally, the setting of the lockdown seems to only add to the sense that they are continuing to perform in spite of the precarity and uncertainty around where to do so.

O’Donoghue, or Post Punk Podge, speaks about growing up in Limerick and going to punk gigs, before performing live in The Curiosity Shop, a truly bizarre setting that only amplifies the theatrical nature of the performance, the artist wearing a beige suit and a mask made out of a brown envelope covered in stickers. ‘Are you happy in yourself?’ asks Podge, performing for the camera with just a shaker in hand.

The group Hey Rusty play inside an otherwise closed Mother Macs, performing in the round with the camera, and by extension the audience, in the middle of their set-up. Sometimes the camera catches its reflection in a mirror, showing us the process of making the film as a part of the work itself.

There is a clear sense that the filmmakers are part of the community they are documenting, and this provides an intimate insight into the processes and lives of the artists they portray. The way in which they lift the veil on the act of making the film reveals casual interactions between the interviewer, production team and the artists, and cooperation emerges as a modus operandi for both the makers and their collective subject.

Empty pubs

Stylistically, the film alternates between black-and-white and colour, shooting in studios, practice rooms, otherwise empty pubs and the musicians’ homes and neighbourhoods, skewing the notion of linear time and moving between the contemporary urgent topics and a reflective, even nostalgic tone that seems to look at the recent past through a hauntological lens.

The film cuts to an interview with the Narolane crew in a photography studio. God Knows tells us that a ‘beautiful gem about the Limerick music scene is that everyone wears different hats, but they wear them well’. The idea resonates with O’Donoghue’s statements that ‘It’s not bricks and mortar that make a city, it’s people that make a city’, adding that ‘everyone genuinely wants to see the other person do well’, a sentiment that seems to run through the film.

For all the humour of Post Punk Podge’s performances, O’Donoghue’s contributions to the film provide some of the deepest insights into both the composition process and the therapeutic and empowering possibilities of making music. In relation to the album Euphoric Recall, he speaks openly about mental health and addiction, arriving at the powerful assertion that ‘what keeps me level-headed is the music really’.

Back in the studio with Narolane, Chaila speaks about the resonant experience of marginalised communities in Limerick: ‘There’s a kinship we feel with the very story of who this city is,’ adding that the fact that Zambian president Kenneth Kaunda visited the city after the country gained independence cements the fact that the ‘city is punk rock. This city is where black revolutionaries came to find respite and rest.’

Portraits

As the film draws to a close, we see Limerick city at night with boarded up windows and empty streets; it then returns to the motif of portrait film photography being developed at home in a kitchen, revealing that the film itself is about process, potentially even the process of portraiture itself.

Before the credits roll, we briefly cut forward to 2022 and the context of a return to live performance, with His Father’s Voice returning to the stage. O’Connor’s closing statements echo the fundamental consideration of the film: ‘Artists are going to create no matter what and everybody knows it. Limerick is no different to any other city. We all face the same problems. We’re all having a very similar experience as musicians trying to find space within all of that. You can kind of see how a future could be forged within a community that is willing to share a space. Where could that space be and what does it look like?’

The fast-forward to 2022 and the band’s return to live performance signals a possible shift in feeling and some hope for change on the horizon. Out of Place has documented the reflections of lived experience and has produced something that anyone who wants a deeper knowledge of the arts in Ireland should hope to engage with, so that they may understand its context. Limerick is portrayed as a vibrant and enduring microcosm of Ireland’s wider problem with a lack of infrastructure for the performance of music. In producing this portrait, the filmmakers have succeeded in creating a lasting document of the artists that make up a city. And although it is a document of a specific time and place, the power of the documentary is in the possible resonance of the experiences and struggles with other artists, and the potential to use this as a catalyst for change.

Out of Place will be screened at the Pálás cinema in Galway on Friday 24 February and at the Model in Sligo on 25 February. Visit https://linktr.ee/feilenagreine.

Subscribe to our newsletter.

Published on 22 February 2023

Drew Stephens is a musician and writer from Connemara.