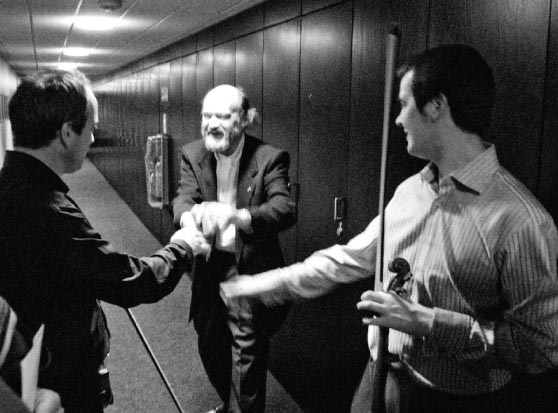

Arvo Pärt with conductor Stephen Layton and violinist Darragh Morgan at a Polyphony rehearsal (Photo: Ian Oliver/Letcombe)

Little Bells make Living Music

This is how it Feels

Earlier editions of the RTÉ Living Music Festival always provided a varied selection of new music alongside the work of a featured composer or group of composers. This year, with Arvo Pärt as the featured composer, a more focused effect was achieved, with many works from him, and relatively few from other composers. I felt it was a pity that the Pärt as the featured composer, a more focused effect was achieved, with many works from him, and relatively few from other composers. I felt it was a pity that the Pärt audience didn’t get challenged much, however, in the way that the Reich audience did with the presence of Feldman’s music a few years ago. Also, the selection of works by those other composers this year lacked coherence, and there was only one Irish work; again, for me, something of a lost opportunity. But as a festival of the subject of Pärt, it was very fine.

The public concept and consumption of Pärt’s output is completely dominated by his works written after 1976, so it was very illuminating to have two works from 1964 and 1968 included: Collage über B-A-C-H and Credo, respectively. The Credo was a stringent and concise collage piece which recalls both Schnittke and Lutoslawski, while the Collage über B-A-C-H was also well-conceived but not quite as strong. What followed the Credo was a long period of silence, self-questioning and reflection, and on his return Pärt embraced the exclusive use of tonal ingredients, with nearly every work using only the notes of a single scale virtually without modulation or chromaticism. These are mostly written using a technique he calls ‘tintinnabuli’ - the word means the tinkling of little bells. In fact it is a sufficiently strict and flexible procedure, in his hands, to allow vast stretches of music where we never hear a truly simple chord (thought we think we do), and the music can roll forward without a hint of closure; forever, if that is required. Although in the stricter tintinnabuli works all that is allowed is skipping within a single triad plus linear ascent or descent, because of the freedom for the rhythm, number of parts and phrase rhythm, he manages immense variety of texture within it. It has been noted that this style evolved after Pärt re-examined the works of late Renaissance composers, but in fact the markers of Pärt’s own voice are mostly original. Pärt’s music would, to Renaissance ears, have sounded abominable and devilish. To further confuse things, Pärt, Renaissance composers and avant-garde music all share a dependence upon (often arbitrary) rigorous systematisation to achieve their effect.

The popularity of Pärt comes down to a collision of factors: that all popular music is diatonic, that people are now used to a lot of dissonance in their diatonic music, the global means of music manufacture and distribution, and the ‘new-age’ phenomenon of large numbers of people searching for something meaningful. Perhaps it also is to do with the quality of the writing which, moment-to-moment. Is usually completely cliché-free and, in its finer details, unpredictable – marks of great artistry (especially within diatonicism where that is extraordinarily hard to do). Repetition is never ladled on with a trowel. Where it exists is not exact. He also allows himself, in secular works, to tweak or partially abandon the structures of his style, and I feel that the weakest points in the music were those where the furthest drift from tintinnabula occurs: Wenn Bach Bienen gezuchtet hãtte, and Für Anna Maria seem much less masterly for it (the latter being a little pedagogical piece, however). When text is involved, he layers on some further strict rules concerning the avoidance of melisma and the musical mirroring of punctuation and these really impinge on the listener to make works such as the Stabat Mater and the Passio austere and abstract. Elsewhere, in instrumental works, we heard freer flights of fancy that may stir the emotions in a rather obvious way, such as a few Hollywood-esque gestures in the otherwise sombre Lamentate, or a slight taste for obvious ending signals to pieces that otherwise remain aloof. With a work such as the Berliner Messe which combines the symphonic and the religious, a very rewarding balance is reached between the freedoms and the liberties of his music.

Pärt’s style is, for contemporary music, exceptionally exposed, and the performer needs to be completely and unwaveringly in control of the notes and tone production. Outstanding performances were not hard to spot, and when they came, as they frequently did in the festival, they lifted the experience to a place beyond the reach of the finest CD reproduction. Every single moment in the choral concert given by Polyphony, under Stephen Layton, was like this, and the programming of a sacred cycle from Poulenc, Quatre motets pour un temps de penitence, interleaved between separate settings by Pärt, worked surprisingly seamlessly. In that concert, his stricter stylistic rules co-existed wonderfully with immense creative freedom and invention. This was particularly the case in I Am the True Vine.

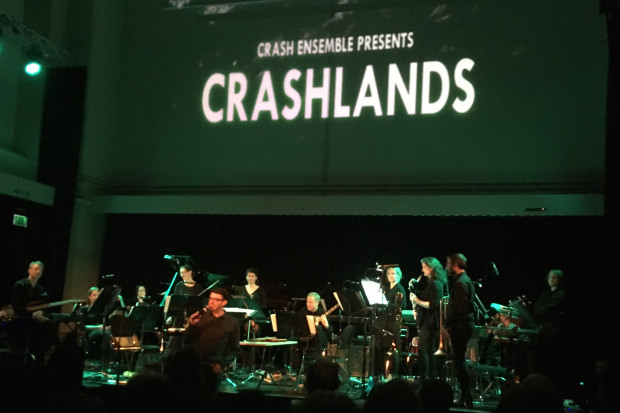

In Crash Ensemble’s concert the very exposed works Für Alina, Für Anna Maria and Spiegel im Spiegel were sublimely delivered by Andrew Zolinsky and Deirdre O’Leary. Joanna McGregor’s contribution to Lamentate, for piano and orchestra, also stood out, and the Vanbrugh quartet gave absorbing accounts of Fratres, Psalom and Summa. Those three are relatively small works, however, and the high point of their concert was Schnittke’s substantial Piano Quintet written in memoriam his mother; with Joanna McGregor on piano. Summa was the most fascinating of the Pärt works there. The Hilliard Ensemble, with the National Chamber Choir and five instrumentalists, delivered the monumental Passio in Christ Church Cathedral. This was again a performance of outstanding quality. Darragh Morgan and Ian Humphries with the RTÉ Concert Orchestra under David Brophy zoomed joyously through Passacaglia and Tabula Rasa, with some of the sweetest and highest violin sounds imaginable. Tabula Rasa as a piece of music is a sweet temptation I can resist, but it is always going to be central to any appreciation of Pärt’s oeuvre.

A trio of Dutch composers, Jacob Ter Veldhuis, Martijn Padding and Peter Adriaansz, featured in the Crash Ensemble concert; they stuck out, maybe intending to indicate how Pärt doesn’t really fit in with the usual contemporary music culture, but in this festival it was they who seemed not to fit. Adriaansz’s Structure XIII was the work most in sympathy, thanks to its polyphonic tendencies. Works by Ivan Moody (string quartet) and David Fennessy (orchestra) complete the list of non-Pärt pieces. Lamentations of the Myrrhbearer, from Moody, was an example of why writing interesting and original music in diatonic language is terribly difficult these days – it was patchy, and seemed to suffer rather than benefit from its religious programmatic content. Fennessy’s This is how it feels (Another Bolero) was a tightly conceived piece that may just have stretched its material too far in the earlier parts, but strode on to a rousing and amusing finale.

The festival also featured a seminar from Ivan Moody on the concept of the ‘spiritual’ in music. It is already clear to anyone with a passing knowledge of Pärt that he became deeply religious within the Orthodox Church around the same time as his development of the tintinnabuli style. In this not very illuminating address and discussion, it became evident that his major pieces, which are all with religious texts, are not primarily composed to be part of a church service; in fact they are concert music. Yet they are created as artistic incarnations for the sacred word, and so, it seems, normal concert-musical aesthetic concerns (if such things can be defined) need not apply. That contradictory situation at least accounts for what one critic so fittingly described as the hairshirt quality of the Passio.

Generally, the more well-known works by Pärt, such as Spiegel im Spiegel, tend to be fairly minimal, airily textured and short. This reflects our instant consumer culture, and not much else; such as where the real music lover should investigate. This festival, by contrast, delivered the musician, the artist, the believer and the person of Arvo Pärt.

Published on 1 March 2008

John McLachlan is a composer and member of Aosdána. www.johnmclachlan.org