Planxty

The Crack Goes On

Back in the sixties and seventies, it was known as ‘crack’, not ‘craic’. Back then, if like me you were into the Belfast folk scene, the crack was that you knew about Dylan and Woody Guthrie and Cisco Houston and Blind Lemon Jefferson and Taj Mahal and Bert Jansch and Davy Graham and Martin Carthy and the Watersons and the Copper family and Ewan McColl and Bert Lloyd. You were into the Incredible String Band. Then there was the Irish stuff: the McPeake family had a rough Belfast edge, but the Clancy Brothers lacked edge. The Clancys were smooth. The Dubliners had edge because of the rough grain of the sound, whether it was Luke or Ronnie singing or Barney going hell for leather on the banjo. For the Dubliners also played reels and jigs, and to our ears it sounded more folkily authentic than the ceili bands you’d sometimes hear your father listening to on Raidió Éireann.

Then we began going to fleadhs in border towns that all began with ‘C’, like Cootehill and Cavan and Carrickmacross and Clones and Castleblaney, and you’d meet people from Dublin and Drogheda and Westmeath and Galway who were into the same kind of crack, folkies who were beginning to discover that Irish traditional music was somehow connected to the American and English scene we had encountered by way of listening to obscure LPs and EPs in dim front parlours on furniture-sized radiograms with wire-grilled speakers the size of meat safes, or maybe we heard some genius in the flesh in a folk club perched on a high stool actually performing the same crack with an intricate finger-picking guitar accompaniment that we’d goggle at in awe trying to work out what the fuck he was doing. We’d sleep in barns and haystacks in hail, rain or snow and venture out in the grey mornings to stagger down the wide main street of the border town draped in broken-zipped sleeping bags if we were lucky enough to have one, straw sticking out of our long hair, looking for the crack. And crack there was. The oul’ boys that had drifted in from the boggy hinterlands of whatever border town it was would be sitting in back rooms in long narrow pubs scraping at fiddles and battering spoons on one another’s knees, delighted that the oul’ music and crack so long reviled by clergy and strong farmers and young whippersnappers was coming back into vogue. Vogue with a vengeance.

All over Ireland, they were at the same crack, as witnessed in abundance by Leagues O’Toole’s excellent account of how Planxty came into being, died, and were resurrected through several incarnations. In the pre-Planxty days in Prosperous, Co. Kildare, Christy Moore and Dónal Lunny and Liam Óg O’Flynn and a rake of other musicians and singers were at it. The crack that is. After the sessions in Pat Dowling’s pub, after the pints and the big trays of thick sandwiches with lots of ham and Branston pickle and mugs of tea, they’d all repair to Dowling’s big Georgian house, which was called Downings, as if it were an after-hours slip of the tongue. They’d go down to the basement with the stone-flagged floor and play until five in the morning relishing the great acoustics and the general crack that went on. There’d be a pair of hob-nailed boots kept on a shelf for anyone to pull on and batter sparks from the flags of the floor if the fancy took them. And in the winter they’d break up the dressers, the chests of drawers, the school benches, the súgán chairs, and throw them on to the enormous open fire. It makes some kind of sense when you learn that there was some kind of antiques business attached to Downings. In Downings a lot of recycling went on, whether of old tunes or old furniture. Round the house and mind the dresser.

Maybe planxty is itself a slip of the tongue. Since Planxty came on to the scene, the word has made its way into the Oxford English Dictionary, and into Chambers’ Dictionary, where it’s defined as ‘an Irish dance tune composed in honour of a patron (Origin unknown, perh. coined by the harpist Turlough O’Carolan, 1670-1738)’. Seán Ó Riada ventured that it might have derived from ‘sláinte’, where a manuscript ‘s’ might have been read as a ‘p’, and the whole thing got garbled into something like ‘pláinste’. Others think it might be from the Latin plangere, to beat or to strike up. If we consider that O’Carolan from all accounts was a witty fellow much given to drink, it might well be a crack of some kind that is now lost on us, and for all we know might have been lost on the Anglo-Irish gentry who patronised him. At one English gig, Planxty were billed as ‘Plan XTY’, like something from a James Bond movie, or aliens from outer space.

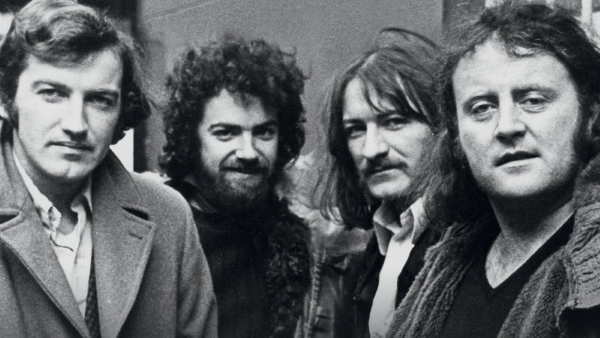

Whatever the case, the exotic name was serendipitous. It stuck, and it came to stand for a kind of aesthetic. And as Leagues O’Toole says, there was something serendipitous in the formation of Planxty. The time was right for the right people to stumble on one another. Planxty was a product of that late sixties, early seventies zeitgeist where everything went into the mix. Its founder members – Christy Moore, Dónal Lunny, Andy Irvine and Liam Óg O’Flynn – had unique musical personalities. Liam Óg especially came from a tradition that was thought almost moribund only a few years before. Christy Moore was a boozy ballad-singer, Dónal Lunny a smart boy in art college who made jewellery. Andy Irvine had been a boy actor, had rubbed shoulders in London with the poet Louis MacNeice, and was given a guitar by Peter Sellers. Yet they were all open enough, and into the crack enough, to come together to make a new blend of music. The instrumentation – guitar, bouzouki, mandolin, uilleann pipes, tin whistle, bodhrán, harmonica, with occasional hurdy-gurdy, harmonium and dulcimer – was unprecedented. The influences – Irish harp and pipes music, Appalachian mountain music, sean- nós, Balkan gypsy music, blues, Irish traveller music – were many and diverse. As Leagues O’Toole has it, ‘they slipped between the cracks of the genres’. The whole ensemble sounded old and new at the same time. They went back to the future and came out with something rich and strange.

They went on the road, and the crack was ninety. In between they got mixed up with dodgy showband managers and slippery promoters and ended up getting ripped off. Phil Coulter, who managed them for a time, wanted to join in on piano, but the boys had the integrity to resist his musical advances. Dope, drink and micro-dot acid were consumed in mind-blowingly large quantities. ‘We are about to dock in Liverpool,’ writes Andy Irvine in 1972, en route to England for the first Planxty tour. ‘It is 5.30h and we all slept in a welter of sleeping bags in a corner of the saloon. The crack is mighty here, we are all excited and got smashed last night and giggled ridiculously.’ Yet behind all the getting smashed and giggling were four immensely intelligent and articulate musicians. Behind the madness there was method. The music was anything but undisciplined. They respected their sources and never compromised the deep structures of the old music. The arrangements were subtle and sophisticated, the melodic counterpoints almost Baroque in their inventiveness. They changed the course of Irish music, and introduced countless people to Irish music.

Leagues O’Toole is a real fan. Sometimes his enthusiasm leads him into the purpler regions of English prose. At one point the band is described as ‘this amazing four-pronged personality’, which puts me in mind of the jig called ‘The Rambling Pitchfork’. ‘Flame-haired’ Luke Kelly sings in ‘an impenetrable broad baritone’. Liam Óg’s pipes are ‘labyrinthine’. No matter. Leagues O’Toole loves the music, and knows what’s going on in it. He is evidently trusted by the musicians, and he has the great sense to let them speak at length for themselves. In interview after interview given by the band members, each comes over as a distinct personality, each with his own manner of speaking and turns of phrase, each with his own slant on events. There are loads of very funny stories, and no bullshit. The book breathes the atmosphere of the times that were in it, and if you want to know something about what led Planxty to be what they were, what kept them going, and what might yet lead them to come together again for another go at the oul’ crack, you should read The Humours of Planxty.

Published on 1 January 2007

Ciaran Carson (1948–2019) was a poet, prose writer, translator and flute-player. He was the author of Last Night’s Fun – A Book about Irish Traditional Music, The Pocket Guide to Traditional Irish Music, The Star Factory, and the poetry collections The Irish for No, Belfast Confetti and First Language: Poems. He was Professor of Poetry at Queen’s University Belfast. Between 2008 and 2010 Ciaran wrote a series of linked columns for the Journal of Music, beginning with 'The Bag of Spuds' and ending with 'The Raw Bar'.