Michelle Mulcahy

Will 2016 be a Turning Point for the Irish Harp?

In the summer of 2014, I returned from three days at An Chúirt Chruitireachta, the Irish harp school that has taken place in Termonfeckin, Co. Louth, for thirty years. That evening, I happened upon a discussion on RTÉ 1’s Primetime about the Irish Government’s then budgetary plans.

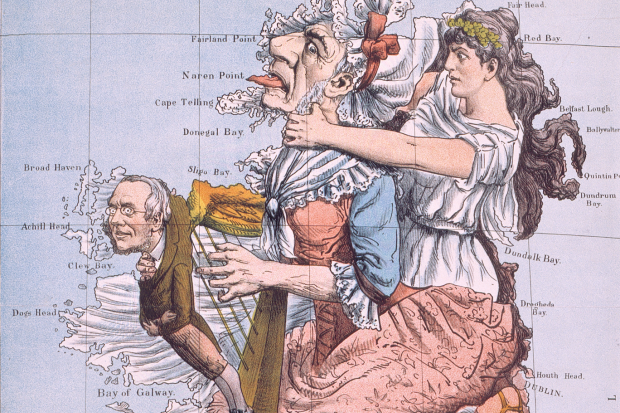

It wasn’t long before I began to notice the large image intermittently flashing up on the television screen behind the discussion. It is an image that in Ireland we have become so used to that it is sometimes almost invisible to us, and yet there it was, at the heart of our national affairs, its presence a perennial reminder of the depth of Irish musical expression, and it is still reaching out to us one thousand years on.

The image of the Irish harp will not just be found in television discussions of the national budget, but on every official letter written by a member of the Dáil, in the logos of state departments, on the President’s seal of office, on Ireland’s coinage and car-tax discs, on the hats of the Police Service of Northern Ireland, on the British pound coin, in the masthead of an Irish national newspaper, in the architecture of the Custom House and the Samuel Beckett Bridge in Dublin, on glasses of stout in every public house in Ireland, and in countless other forms relating to Irishness, not only in Ireland but throughout the world.

What does it mean to have a musical instrument as a national symbol? And what do we know about this instrument that we see every day, but do not hear often enough? The truth is that having a harp on our coins only really matters if we give meaning to that symbolism – through engagement and action. The harp has the potential to be not just a symbol of the country’s historic culture, but of how the state cares for its musical traditions into the future. It is because of the harp’s deep role in Irish society over a millennium that this opportunity is so meaningful.

The harp’s musical future

The reason for my trip to Termonfeckin in 2014 was to carry out research on behalf of the Arts Council. That research, titled Report on the Harping Tradition in Ireland, was published last week and is now available on the Arts Council’s website. Containing 96 pages of analysis and 14 separate recommendations, it offers a roadmap for the development of this remarkable tradition and instrument. From instrument hire to new events and festivals, from the setting up of a forum for harpers to support for key organisations, from the development of a national harp centre to harp making, there is a range of things that can be initiated in 2016 to strengthen the musical future of this national symbol.

When we think of Irish harping, diversity must be a key word. It is an instrument that has been played on this island since around 1000 AD, making its practice several hundred years older than what we regard as traditional Irish music. It is multi-faceted and challenges our contemporary definitions of musical genre.

Indeed, there is not just one harp played in Ireland today but several, most prominently the Irish lever harp, the early Irish harp, and the concert harp. And there is further variety in how each harp is played.

Yet, as a community of musicians, there is one issue on which harpers are united, and that is that the low profile and outdated image of the instrument is a stumbling block towards its future development. The image of the ‘Irish colleen’ playing background music and singing wistful Irish songs is not the reality of the contemporary Irish harping scene. Bubbling beneath this cliché is an art form that is alive and virtuosic, with young talent such as the Meath and Laois Harp Ensembles, and exceptional artists such as Michelle Mulcahy, Laoise Kelly, Cormac de Barra, Siobhán Armstrong, Tríona Marshall, Janet Harbison, Michael Rooney, Máire Ní Chathasaigh and more.

To many Irish people, however, the harp has become something remote. It has not had the prominence of other aspects of cultural life, nor the caché. There was no harper at the Royal Albert Hall for the Ceiliúradh concert to celebrate the Irish president’s first state visit to Britain, nor was there one in Riverdance. And yet, through an extraordinary effort over the past six decades, there has been a great revival in Irish harping – recognised last week by a special TG4 Gradam Ceoil award for Cairde na Cruite (‘Friends of the Harp’), which has spearheaded the movement.

There is so much more that still has to be done, and there is something magical about the idea that this symbol of Ireland – which the world has become so accustomed to – could play a much bigger part in contemporary musical life. The small harp community has already travelled a lot of this distance itself, against the odds. The opportunity and the research is now there for the Arts Council and the state to bring it even further.

–

Report on the Harping Tradition in Ireland, written by Toner Quinn, is available to download on the Arts Council’s website.

Published on 25 January 2016

Toner Quinn is Editor of the Journal of Music. His new book, What Ireland Can Teach the World About Music, is available here. Toner will be giving a lecture exploring some of the ideas in the book on Saturday 11 May 2024 at 3pm at Farmleigh House in Dublin. For booking, visit https://bit.ly/3x2yCL8.