Mary Dullea and the score of Eric Craven’s Sonata No. 8.

Taking the Listener Everywhere and Nowhere

Ferruccio Busoni’s dictum that ‘everything is possible on the piano, even when it seems impossible to you, or really is so’ points to the abiding provocation and promise of the instrument to composers. And to pianists.

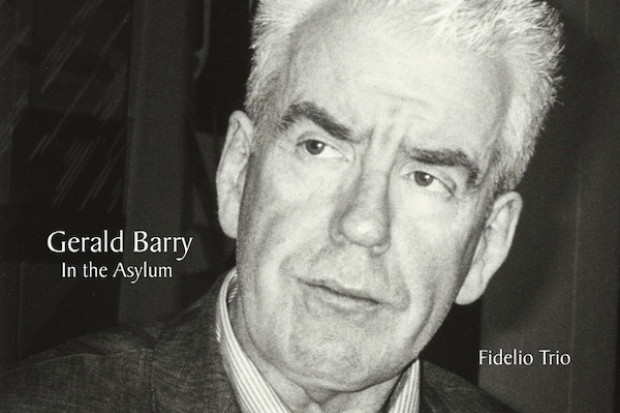

Two new releases by the Fidelio Trio’s lynchpin pianist and committed new music advocate Mary Dullea, Eric Craven: Piano Sonatas 7, 8 & 9, and Gothic: New Piano Music from Ireland (both on the Métier label), serve as telling tests of Busoni’s assertion. In their separate but over-lapping explorations of pianistic sound they point to the abiding centrality of the piano to contemporary composition while also illustrating the instrument’s capacity for accommodating both full-frontal assaults and guerrilla-like incursions.

Eric Craven’s three un-dated sonatas (Nos. 7–9) pointedly employ both stratagems. One of the most enigmatic British composers of his generation, he emerged tentatively out of self-imposed isolation for his debut on disc in the company of Dullea with 2011’s Set. As eclectic in its conception and execution as Craven is elusive about point, purpose and context, Set was a scrambled amalgam of inscrutable musical hieroglyphs designed to obscure as much as to enlighten.

Whether the sonatas bring him into any clearer focus remains moot. Infer what you like from their borrowing of classical form, but if there is biographical intent here it’s not to be gleaned from the technically accented booklet notes or from the music itself. Instead, it is Craven’s self-coined ‘non-prescriptive’ technique that tasks interrogator and listener more than any glancing stylistic allusion.

That none of the seven Irish composers featured on Gothic offer so explicit a philosophy or frame for their experiments and explorations makes its own comment. Belonging to a generation that owes as much to inherited traditions as to the possibilities of the present, they are clearly beholden to neither in equal measure.

Perhaps the issue here is age. Despite his protestations of recondite individuality, Craven’s music feels obdurately grounded, albeit its foundations and anchors are discrete and disguised, hedged by and hidden within a compositional language reluctantly rooted in the conferred certainties of the past. But while he posits himself in opposition to that past and seeks to differentiate and distance his music from the present, the sonatas’ restive references to the extremes of Wagner, Sorabji, Tippett and variant points in between betray the confinements of both. (Conspicuously less agitated, more at ease in their own pluralist time and accommodating temper, are the younger voices on Gothic.)

The ‘hall of mirrors’ that is Craven’s 49-minute, single-movement Eighth Symphony – ‘a vast array of “parcels” of sound that may be played in any order’ – plays with the unsettling notion of identities fractured and refracted out of recognition, globules of sound time and again coalescing into near-definition only to disperse before they can be recognised and fixed. Dullea treats the work as a sonic jigsaw of countless permutations, a virtual archipelago of shifting motivic landmasses washed repeatedly by shifting waveforms and the flotsam and jetsam of drifting harmonies. What results, the booklet revealingly notes, ‘takes the listener everywhere and nowhere’.

What is implied or simply omitted – tempo, dynamic, phrasing, articulation – in Craven’s Seventh Sonata (‘a maze in the form of an arch’) is ‘filled in’ by the pianist. There’s something here of jazz music’s surrendering of the primacy of the composer to the immediacy of the performer, a conceit that rubs shoulders with improvisational licence while maintaining discernible control from a distance. Dullea fills in the blanks to telling effect, adding sinew and flesh to bare bone, finding flex and flux in the motivic crux of music that moves osmotically from loose-limbed jazzy inflections to taut, knotty modernity.

Defining threads, intentionally ravelled

Gráinne Mulvey’s Étude (1994) and Ed Bennett’s Gothic (2008) grapple with similar dilemmas; the former’s gymnastically described arc bridging one virtuosic demand after another, the latter conjuring an eerie evocation of Notre Dame Cathedral at night that makes much of claustrophobic chordal clusters and Dullea’s unsettlingly under-stated keening.

Dullea’s humming voice is there, too, in David Fennessy’s memorial to Scottish poet-playwright Tom McGrath, the first thing, the last thing and everything in between (2009), its dark-hued but luminously resonating chords brokenly chiming with the Aria from Bach’s Goldberg Variations.

Frank Lyons’ Tease (2009) for piano (played inside and out) and live electronics echoes Craven’s cutting loose from auteuristic impulse, the ordering of its 12 miniature movements left to the whim of the pianist in a piece that tests the base, brute mechanics of the instrument to eloquent effect. Approaching similar territory from a different trajectory, Benjamin Dwyer’s two-part Homenaje a Maurice Ohana (1999) is built on broiling textural quicksand and makes much of light and shadow, timbral resonances and incestuous harmonies as if the whole was viewed through a cracked mirror.

John McLachlan’s allusively variegated Nine (2011) – in which limited, non-repeating rhythmic and pitch patterns are constantly diffracted – is kaleidoscopic, too, although more by compositional design than Craven’s surrendering to interpretative chance.

The ghosts of Debussy and (more so) Scriabin are fleetingly seen in the floating scraps of whole-tone scales of Craven’s Ninth Sonata, and in the near pathological tendency of its phrases to wander away from key signatures into less securely signposted terrain. Contrastingly, Jonathan Nangle’s grow quiet gradually (2008) finds an increasingly vehement eloquence in the self-imposed restrictions of its more limited vocabulary, one that constantly returns to its opening two-chord source and arpeggiated motif in search of a greater expressiveness that is securely mapped by the self-reflectingly compact scale of its geography.

Both discs find composers revelling in the intricate warp and weft of music in which defining threads are intentionally ravelled, deliberately obfuscated or omitted altogether. They draw one back to Busoni’s comment but suggest a developing shift away from the boundaries of a composer’s imagination to the limits of a performer’s technical abilities, offering up the alluring prospect that what ‘seems impossible… or really is so’ on an instrument as venerable and venerated as the piano might actually become possible.

Published on 15 February 2015

Michael Quinn is a freelance music and theatre journalist based in Co. Down.