The Sound of Discovery

Sometimes the most profound listening experiences occur when you least expect it – and leave one wondering if such eureka moments can ever be repeated. Visiting the Festival de Jazz et de Free Music in Mulhouse, France on a whim in 2004, and returning in 2005, Barra Ó Séaghdha discovered that they can.

I went to my first festival in Mulhouse in August 2004 because, after an exhausting summer, I was too overwrought to simply do nothing, because listening to a lot of music would help me to relax and retune while providing a kind of focus at the same time, because the line-up seemed varied and promising (though there were many musicians I didn’t know), because it was in France and I can speak French, and because it was cheap. I went to my second, last August, for many of the same reasons, because I had been impressed by the first on so many levels, and because I realised that the format of the festival meant that a second visit could not help but be more interesting than the first.

Now past its industrial heyday – it has undergone the standard transformation from heavy industry to museums of heavy industry – the modestly sized city of Mulhouse goes about its business unfussily. As it caters largely for its own needs, there is no sense that the voracious natives are waiting to fall upon and rend the unsuspecting tourist. Those who combine a taste for avantgarde music with more traditional taste in food will be happy with the hefty helpings of spuds and (Alsace-style) bacon and cabbage slapped on their plates. More importantly, the city is generous to festival-goers where transport and accommodation are concerned. And the friendliness and efficiency of the team behind the Festival de Jazz et de Free Music also create an atmosphere in which relaxed appreciation of the music can flourish.

Let’s not worry about labels for the moment. Whether arriving from the world of jazz, of contemporary composition, of free improvisation or of techno as it shades into freer forms, anyone with open ears and mind would recognise – without necessarily being drawn to – the commitment, versatility and technical accomplishment of musicians like Louis Sclavis (saxophones and clarinets), Barry Guy (double bass), Axel Dörner (trumpet), Ernst Reijseger (cello), Ken Vandermark (saxophones, clarinets), Conny Bauer (trombone) or Joe McPhee (saxophones, trumpet) – all of whom took part in the 2004 festival. The music they produce ranges from the totally free to the tightly composed, from solo to sizable ensemble, from extravagance to austerity.

Before going any further, let us also admit what needs to be admitted. Particularly in free improvisation, without the support of a predetermined structure, the occasion may simply fail to spark, players may fall back on personal and group cliches or create a factitious excitement that disguises a loss of creative spirit. This is a kind of music that demands acute reponsiveness, an intensity of listening as much as of playing. For some, this may prove unsustainable in the long term.

Crashing over me in waves

My own first exposure to the music was completely accidental. One evening when I was in my twenties, at the end of a month in Canada during which nothing had gone according to plan but many interesting things had happened, I found myself wandering the streets of Montreal with nothing to do. As I went past a jazz club, I vaguely recognised the name Anthony Braxton from an article about jazz that I had read shortly before. With little idea of what to expect, I went upstairs to a room where fifty or sixty people were waiting. There was a bank of percussion on one side of the stage, an array of wind and brass instruments – as well as various unidentified objects – in the centre, and a double bass on the other side. A polite and modest-looking man – his glasses, pipe and cardigan suggesting an academic on a day off – led three other musicians onto the stage. Within minutes I was gaping in astonishment as sounds I had never heard in my life came crashing over me in waves. I had nothing to hang on to, no reference points, no idea where the music was going, but the intensity of concentration that the musicians showed, the orchestral force that they could summon up between them, the ability they had to sweep towards heights of screeching violence only to relent and invest equal intensity in the lightest of brush-strokes, the humming of a string, the faintest of breathing – all this left me no choice but to ride the waves and give up all thought of shore, which is where I was tossed, gasping beatifically (is that possible?), fifty minutes later when the first set concluded.

Experiences like this do not come often and there can be a particular intensity to the moment when a whole new form of experience opens up. A few years later disappointment with another Braxton quartet was soon followed by an evening of sheer wonder when he played with the electronic player/composer Richard Teitelbaum. (Braxton had been associated with Musica Elettronica Viva for a period.) It was like hearing, and this time understanding, music from another planet. On the street and in the Metro afterwards, joy at what I had heard was mixed with melancholy at the thought that I could not keep every moment in my head, that the vividness might drain away.

Creating contexts

A festival like Mulhouse cannot guarantee such an experience, but its aim should be to create the conditions for it. The number and quality of musician that plays there make this a real possibility. One of the attractions of Mulhouse is that many musicians appear in more than one format, so that it is possible to gain a multi-dimensional experience of a player, to sense the limits or the horizons of a particular talent, and to recognise the contexts in which that talent wilts or flourishes. That many players are happy to come back again and perform in yet more contexts makes this a particularly rewarding event. As a result, beyond the individual concerts, the festival does outstandingly what festivals aspire to: it takes its audience to the heart of a whole sector of creation.

On Tuesday night in 2004 you could see Louis Sclavis (bass clarinet and soprano sax) nudged across the border of his own language and then excited by the challenging syntax of a trio of younger French players (Delpierre, Jérôme, Gleizes); the following night his own group presented Napoli’s Walls. In the beautiful disused Chapelle Saint-Jean at lunchtime on Thursday, you could witness the dialogue between two trumpet-players, the cool, pared-down precision of the German Axel Dörner and the more ebullient, corporeal presence of the Frenchman Jean-Luc Cappozzo; late that evening, Dörner would perform in a completely different context, with a reed-player and a percussionist from Sweden (Sture Ericson and Raymond Strid) and a Norwegian double-bass player, Ingebrigt Håker Flaten. In 2005, Cappozzo would appear in an energetic French quartet (Solex) and in a loose, colourful and hugely enjoyable performance by an international brass and percussion ensemble (Le Grand Huit), featuring such talents as the New York trumpeter Herb Robertson, the Bauer brothers with their contrasting trombone styles, and Raymond Strid.

Some of the musicians mentioned above have performed in Ireland in relatively recent times. Ernst Reijseger is one example. He has played here and given master classes in the cello. Anyone who has seen him will know the extraordinary range of techniques of which is he a master: he can use the bow in the conventional manner; he can use extended techniques to draw all kinds of sound from his instrument; he can strum it with equal facility, as if playing the guitar; and, drawing on the varying resonance of every square inch of the surface of the instrument, he will turn percussionist and rub, rap, scratch and otherwise violate the sanctity of the cello. Seeing Reijseger in action over two festivals, it became clear that this degree of versatility sets its own challenges.

In 2004, Reijseger performed in two very different settings. Along with two Dutch-based Senegalese musicians, Mola Sylla (vocals) and Serigne Gueye (percussion), he performed in Systeme D. Their music was a meeting of African tradition (rhythm, singing style) and European improvisation. What was interesting was that when Reijseger, though a member of a Dutch generation which often mixes mockery and a taste for the extreme, moved towards more elaborate improvisation, his creative instincts seemed grounded in and guided by respect for the rhythmic/melodic language from which he had started. Something very similar occurred the following evening when Reijseger played in a quartet (Fifty 4) presided over by the virtuoso avant-country banjo and theatrical persona of Eugene Chadbourne. With Johannes Bauer playing with visible delight but in a rather programmatically free manner, and with Martin Blume opening beer bottles, squinting sceptically at proceedings and playing percussion with a timing and deadpan nonchalance that Buster Keaton would have admired, Reijseger’s playing was this time rooted in country idiom and rhythm but creating a deft, almost elegant version of his own.

There was every reason therefore to look forward to his appearances in 2005, the first of which was in the company of a long-time collaborator, the percussionist Alan Purves. It soon became clear that this was going to be a pointless, uninvolving and ultimately irritating emptying-out of each musician’s bag of personal tricks and techniques. Reijseger bowed a bit, plucked a bit, strummed a bit… Purves showed that it is possible to blow simultaneously and rhythmically through multiple items of tubing and plastic inserted in nostril and mouth, but he did not show why we should care. Reijseger’s solo performance the next day was a little more focused, but I found myself musing on the loneliness of the long-distance virtuoso.

The spirit of Montreal

Barry Guy, too, could be described as a virtuoso, though he also composes in both the contemporary/classical and the jazz idioms, and he has been exploring composite baroque/contemporary forms in collaboration with violinist Maya Homburger. In 2005 Guy was to play twice, with fellow-bassist Bruno Chevillon (who has appeared on many Sclavis recordings) and with his own band, the BGNO (Barry Guy New Orchestra). Guy and Chevillon had never played together before. The result of their meeting was intriguing – and in sharp contrast with the Reijseger/Purves duo.

Those familiar with Barry Guy’s playing will know that his speed of execution is matched by speed of thought: seeming to hold the shape of the performance as a whole in mind as he proceeds, he responds instantly to the detail of other musicians’ playing, while both shaping his own line and unselfishly offering ideas and space to those around him. It is said that, because of the configuration of our ears, what we hear in the singing of a robin is quite different from what the bird hears. Notes that flick past us may be fully articulated to the bird’s ears. Guy can operate at a speed that our ears strain to match, but his inherent sense of design means that he will also create variation within speed, move from one texture to another and balance fast with slow. On this occasion, Chevillon was playing like a man posssessed – but a man possessed, even if playing very well, may not always be the ideal listener. When Guy shifted gear, opened up a little space or otherwise proffered suggestions, Chevillon did not always take the hint and drove on regardless. The music was frequently exhilarating nonetheless.

I have never heard Barry Guy engage in musical doodling or ask less of himself because the audience is small or the occasion unprestigious. This ethic of respect – for music itself, for himself as performer and for the audience – is a discipline that also keeps the springs of creativity fresh. As leader, composer and player, Guy infuses the BGNO with the same ethic. The musicians he has chosen – among them leaders in their own right, such as Evan Parker, Herb Robertson, Hans Koch and Mats Gustafsson – aspire to similar discipline and freshness, while the structure mapped out for them allows for generous expression of the individuality and particular qualities of each player. (The Mostly Modern festival of 1998, a week of music that led to the inaugural concert of the BGNO in Dublin, was a highwater mark for improvised music in Ireland. Whatever the reasons for it, the failure of the Irish music world to build further on Guy’s presence in the country was a great opportunity squandered.)

This happy multiplicity of talent was in action again for the performance of Oort-Entropy at Mulhouse. With Guy at the fulcrum and pianist Agusti Fernandez (showing tremendous command and range) a near-constant presence, the three-part piece – a complete reworking of compositions originally written for trio – involves a constant reconfiguration into duos, trios, solos with or without backing, full-blown and full-blowing ensemble…

On the night, nobody – from the relatively obscure but superb tuba-player Per-Ake Holmlander to the veteran saxophonist Evan Parker – played below his best. There was sheer drama in the way Mats Gustafsson’s baritone came surging out of a seething orchestra and a different drama in the unshakable authority with which Parker stamped his solo. And then there were the slow, searching passages, or those when the whole orchestra became a single many-hued song of jubilation. This was music that renewed the innocence of the listener. In that sense, it sent me back to the spirit in which I had discovered this musical territory one evening years before in Montreal.

If the BGNO performance alone would have made the 2005 festival worthwhile, other musical philosophies could also be experienced. In the Chapelle Saint-Jean, using only a bass drum and some simple percussive imstruments and implements, Le Quan Ninh’s multi-layered undulations had an appropriately ritualistic intensity. There was nothing of the self-indulgent poking around that is in danger of becoming a contemporary cliche about Sophie Agnel’s precise, tightly focused explorations of the interior of the piano (in a duo with guitarist Olivier Benoit). These musicians would derive more from AMM’s sonic explorations than from in-your-face free jazz.

Listeners, like musicians, can have their off-days. Was it a lack of receptivity on my part that left me relatively indifferent to the duo of Peter Brotzmann and Joe McPhee (a musician I admire enormously)? And even the presence of the endlessly fluent pianist Irene Schweizer, or that of bassist Joëlle Léandre when she avoided the ho-ho-ho stuff, could not induce me to ungrit my teeth at Maggie Nicols’ flirtatious and self-satisfied ramblings (with all due respect to her accomplishments elsewhere). Better to think of more positive surprises – Hasse Poulsen’s miked acoustic guitar bursting through a wall of saxophone and percussion to pound out a long fearsomely rhythmic groove; or the young French drummer Edward Perraud, not only holding his nerve, but almost cheekily imposing his right to share a stage with senior players such as Herb Robertson and Connie Bauer as part of Le Grand Huit.

I can thrill to the sound of Maighréad Ní Dhomhnaill singing an unaccompanied lament in Irish, to the great flamenco singer La Niña de los Peines intoning a seguiriya, to Maya Homburger playing Biber, to many other great moments in music. But I would be happy if there were more people with whom to share the special thrill of the best improvising musicians surprising and renewing themselves – the sound I discovered in Montreal and rediscovered in Mulhouse.

Anthony Braxton’s first solo record, For Alto, still retains its power. His quartets of the mid- to late 70s, and again of the mid-80s to early 90s, are probably the best entry to his extremely varied work. His Six Monk’s Compositions, or his appearance on David Holland’s Conference of the Birds, might surprise the doubters. A studio recording of Barry Guy’s Oort-Entropy can be found on an Intakt CD; his Folio has recently been issued by ECM. Information and much fine music, including solo recordings, can be found on the Maya Recordings website (www.mayarecordings.com). His career can also be tracked through the long history of the Evan Parker/Barry Guy/Paul Lytton trio. Ernst Reijseger has an extensive discography. Two representative CDs on which he can be found in good company are the Gerry Hemingway Quartet’s Special Detail and Clusone 3’s Soft Lights and Sweet Company, both on Hat Art. One of the best sources of music on the whole sector is http://efi.group.shef.ac.uk

www.jazz-mulhouse.org is the website for anyone curious about the Festival de Jazz et de Free Music.

Published on 1 March 2006

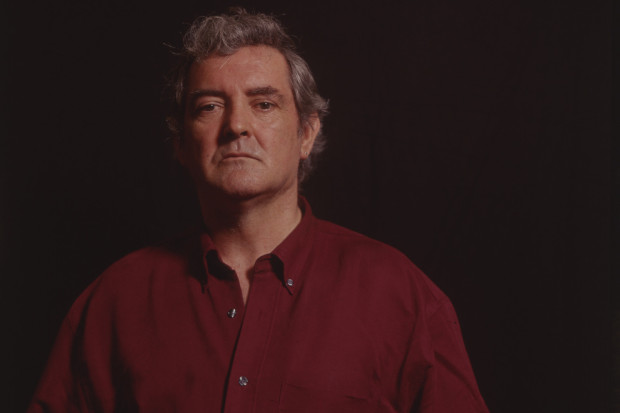

Barra Ó Séaghdha is a writer on cultural politics, literature and music.