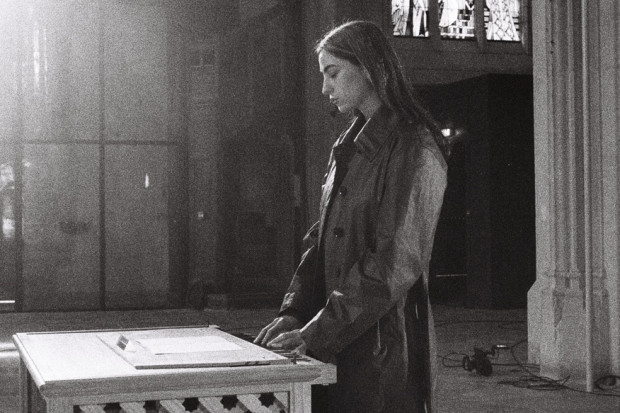

Booby Casey

The Small Back Room

The Small Back Room is the title of a novel by Nigel Balchin (1908–1970), a writer I had thought almost forgotten until I looked him up on the internet to find that according to Clive James he is ‘still widely read’. I also discovered that Balchin, an industrial psychologist who worked for Rowntree’s at one stage of his career, is credited with the invention of the Kit-Kat bar and with putting the bubbles into Aero. During the Second World War he was a scientific adviser to the British Army Council, working in an atmosphere of top secrecy. He was, in effect, a ‘boffin’ or ‘back-room boy’, terms which were popularised by The Small Back Room.

Perhaps Balchin was never widely read in Ireland. He was a quintessentially English writer. Published in 1943, The Small Back Room became an instant bestseller. Briefly, it involves the efforts of a bomb-disposal expert, Sammy Rice, to counteract both the unexploded bombs dropped by the Germans and the bureaucracy of his own higher command. It is a story of individual courage and intelligence, of dealing in complex and difficult realities instead of procedural formulae. The eponymous Room is where things get done.

Knowing nothing of its contents, I was first drawn to this book by its title, which I came across on a shelf of the Belfast Central Library some time in the early 1980s. It had often occurred to me that the ideal space for a performance – if that is the right word – of traditional music is a small back room. One of the first places I encountered the music was the upstairs back lounge of Pat’s Bar in Prince’s Dock Street, a long, narrow, extended return room with wooden benches ranged along the walls and a long narrow table in between. Music bounced from the floor and walls; you felt yourself encompassed by the sound. Later I came to know the back kitchens of pubs in border towns like Clones, Cootehill and Castleblaney, where the musicians would be smuggled in after hours along with a few lucky camp followers to play into the small hours. Later still I got to know similar small back rooms in the likes of Ennis, Feakle and Enistymon, and was fortunate to get to hear the likes of the late Junior Crehan, John Kelly, Joe Ryan and Martin Rochford – fiddle masters, men of consummate musicality, intelligence and wit. Later still again I came across Bobby Casey’s tape Casey in the Cowhouse. This is an epitome of music played in a small back room, recorded on a Grundig reel-to-reel tape recorder in a converted barn or shed at the back of Junior Crehan’s house in 1959, and issued as a commercial cassette in the mid-1980s.

It’s been some years since I’ve listened to it, and I’ve been trying for some weeks to find that cassette again. In vain have I ransacked the front room and back room and bedrooms and return room of my house, where shelves, boxes and piles of books and records languish in various states of entropic order or disorder. I have a suspicion that I might have loaned it to Bernie the fiddler, and never got it back, but when I confront him at the weekly session he denies all knowledge of this. His own tape is a copy, whether of mine or someone else’s he cannot say; but in return he promises to give me a CD copy of the tape, and the week after he does just that. What I’m missing, though, is the liner notes, so any circumstantial details mentioned here – the Grundig, the exact location and year of the recording, for example – have been gleaned from an internet trawl.

In any event the music is the thing. Bobby Casey emigrated to London in 1952, along with Willie Clancy, who returned to Clare shortly afterwards. Bobby stayed. In his essay ‘Bobby Casey: Virtuoso of West Clare’, Kevin Crehan – a nephew of Junior’s – recalls the social circumstances of the music:

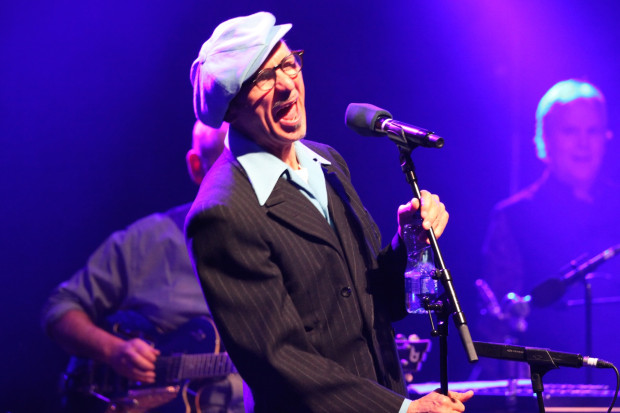

By the early 60s the Irish population in London had been steadily growing since the 30s. It had become quite acceptable to play music in public houses and indeed many Irish people would patronise public houses based on the same parochial and townland associations of their youth. It was the custom that any neighbour from home would come out and buy a drink for their local musicians, a testament to their support, appreciation and patronage. At the end of many nights, and particularly when Bobby played, there would not be space left atop the piano to hold the drink that was offered in tribute.

There is a lonesome note in Bobby’s music, but also devilment and wit, a razor-sharp awareness of the possibilities of a tune, of how a subtle twist to a conventional run of notes can transform what until then seemed mournful into something wry and funny. The humour is deadpan and sometimes wicked. I had the good fortune to meet Bobby once. By this stage of his life he had moved to Northampton, and I was introduced to him at an Irish festival in Birmingham. At the end of the night a gang of us were whisked off to the house of a friend of Bobby’s, deep in the English countryside, a huge rambling Irish builder’s house it seemed to me, with illogical staircases and landings and rooms crammed with musical instruments. In one of these rooms Bobby held court. Like many of the Clare fiddle masters I’ve encountered, he barely seemed to move his bow hand at all, and I was flummoxed by the deft, articulated notes that sprang from the fiddle without that much visible manual intervention. In between and sometimes during the playing Bobby would be throwing out a stream of one-liners, lovely, quick shafts of wit emerging as commentary to the music and the conversation. One minute the audience would be captivated by the beauty of the music, the next cracking up with laughter. I like to think that the atmosphere in the cowshed was something like that. I can imagine whoever was there enraptured by one set in particular, where he plays five jigs in a row, heads nodding with appreciation and delight as one tune sparks off the next to new levels of invention. It is a majestic performance, and full of devilment.

Farfetched though the comparison might be, I think Nigel Balchin and Bobby Casey had something in common. ‘Balchin,’ says Clive James, ‘was a gifted logistical thinker – a natural critical path analyst with a remarkable capacity for absorbing the detail of new fields. He dealt in realities, the art of the possible. The test was relevance.’ Bobby’s technical gifts were such that he could do most things that are done in traditional music; but he never showed off for the sake of showing off. The music is as much about what he left out as what he put in. He could analyse the possible permutations of a tune and turn them to a new and immediate purpose. It is relevant to the moment, to the here and now. It subverts the procedural formulae. It deals with real emotion, with longing, with exile, with how people relate to each other, and it does so with courage, grace, intelligence and humour.

The next article in this series will be called ‘The Art of the Possible’.

Published on 1 September 2008

Ciaran Carson (1948–2019) was a poet, prose writer, translator and flute-player. He was the author of Last Night’s Fun – A Book about Irish Traditional Music, The Pocket Guide to Traditional Irish Music, The Star Factory, and the poetry collections The Irish for No, Belfast Confetti and First Language: Poems. He was Professor of Poetry at Queen’s University Belfast. Between 2008 and 2010 Ciaran wrote a series of linked columns for the Journal of Music, beginning with 'The Bag of Spuds' and ending with 'The Raw Bar'.