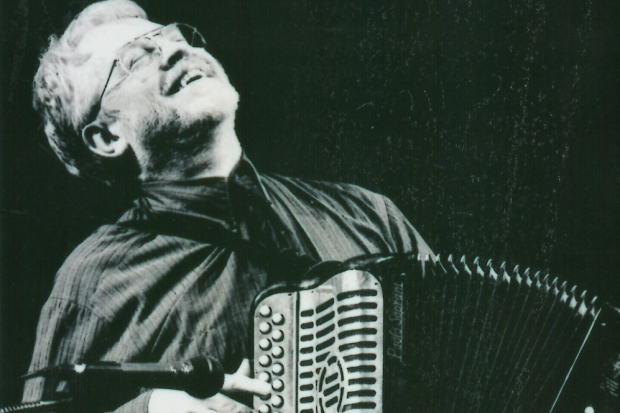

Liam O’Connor and Seán McKeon

Repeat Experience

The traditional musician plays the tune, then they play it again, then they play it again, then they change to a different tune, play it through, then play it again, and then play it one more time, and then stop. Or they’ll continue into another tune, and play it again, and again, and again, and then stop, or venture into another. Each part of a tune is played twice, and each part consists of a two very similar phrases. If there is more than one musician playing, everyone will essentially play the same tune. Most of the repertoire is written in just a handful of keys, and even fewer time signatures. Is it any wonder that traditional music has a reputation for being repetitive?

Repetition in any listening experience has the potential to bore, and so the way in which a traditional musician navigates a tune for the listener – using ornamentation, variation and any number of other devices – is central to their success as a performer. It is a major challenge in the art form, but, for the outstanding traditional musician, it is also an opportunity to set themselves apart from the crowd in an ever-more populated traditional music scene.

Because traditional music is repetitive (and those who find little to interest them in the art form often cite this aspect as the culprit), to emphasise repetition in performance, to push it as far as it can go, say by continually repeating a tune beyond what is standard practice, is a particularly daring thing for a traditional musician to do. Virtuosity is becoming more widespread, repertoire is more accessible than ever, and speed can be easily matched, but extreme repetition is one area into which few musicians are willing to venture.

Executed well, it can have a trance-like effect on an audience – that quintessential traditional music image of the entire room all nodding and tapping at the same time – or it can bring a new level of intensity to the listening experience as the performer increases the temperature with every repeat. Carried out poorly, however, it can appear self-indulgent, which is probably the worst description you can receive in a music so social! For sure, it is in extreme repetition that a traditional musician walks the thinnest of tightropes.

Any cursory description of traditional music will state that traditional musicians tackle such repetition by using ornamentation and variation to maintain the listener’s attention, but while many do indeed do this, there are plenty of exceptions to that rule, and there is so much more to it than that. In a recent performance by Paddy Cronin on the television series Come West Along the Road, the Kerry fiddle player hardly changed a note in a reel although he played it three times. Kevin Burke too, often recorded sets with very little variation.

Popular wisdom would also suggest that melodic variation increases in complexity with each repeat, but it is often the case that variation will be reduced radically just before changing tune, or towards the end of a performance – a piloting down of the audience after all the dizzy heights.

While artists such as Noel Hill, Frankie Gavin, Martin Hayes, Tony MacMahon and others would be pioneers of extreme repetition – Gavin’s Irlande album from 1994 immediately comes to mind – young fiddle-players such as Liam O’Connor appear to also favour it as a device in performance.

Rogha Scoil Samhraidh Willie Clancy is a double-CD collection of performances from the 2007 Miltown Malbay week on which O’Connor plays ‘The Duke of Leinster’ solo. Because in the performance he is to be joined by Noel Hill on the second tune, ‘The Humours of Ballyconnell’, the fact the he moves beyond the standard approach of two repeats and plays the reel four times over is even more striking. That simple act of playing it one extra time becomes a statement in itself, a setting apart of one’s music from orthodoxy. (In a similar masterclass in extreme repetition on the same recording, concertina player Hill plays the single jig ‘The Foxhunters’ fourteen times before moving on.)

The particular approach to variation used by Liam O’Connor – a mix of complex ornamentation, skilful bowing, and a sporadic, subtle dragging of the rhythm – is striking. Combined with his appetite for extreme repetition, he has set himself apart in the current scene. All of this is evident in the newly-released CD with the similarly skilled uilleann piper Seán McKeon, entitled Dublin Made Me. The pairing of O’Connor and McKeon is well established in traditional music through many stage performances, but it is still difficult to ignore the sense that Dublin Made Me signals the arrival of something new – a particular twenty-first-century-Ireland type of youthful confidence and assurance perhaps. It is stripped down instrumentally, yet loaded with contemporary ideas, characterised by a virtuosity, technique and rhythmic quality which seems to point to the influence of the mainstream contemporary music world that surrounds us – and yet, somehow, that scene is hardly anywhere to be seen. It is almost as if decades of experimentation and technical advance in traditional music have been distilled surreptitiously back into the single melodic line and the unaccompanied duet. The only addition to the duo – and it is an untypical one – is Ciarán Mordaunt playing subtle rope, snare, tenor and bass drums on a couple of tracks.

O’Connor takes the opportunity to return to ‘The Duke of Leinster’ on Dublin Made Me, in this instance performing the familiar reel five times over, accompanied by no other tune or musician. Again, it is a serious musical statement using extreme repetition, employing such a range of techniques that fragments leap out as if part of a classical concerto. Seán McKeon takes a similar approach in his piping solo of two reels, ‘The Ladies’ Bonnet’ and ‘The Pinch of Snuff’ – boring down into the second tune in particular, though it is never boring.

Repetitive traditional music may be, but performances such as O’Connor’s and McKeon’s make it very difficult for traditional music to repeat itself, or stay still even for a moment.

Published on 1 November 2008

Toner Quinn is Editor of the Journal of Music. His new book, What Ireland Can Teach the World About Music, is available here. Toner will be giving a lecture exploring some of the ideas in the book on Saturday 11 May 2024 at 3pm at Farmleigh House in Dublin. For booking, visit https://bit.ly/3x2yCL8.