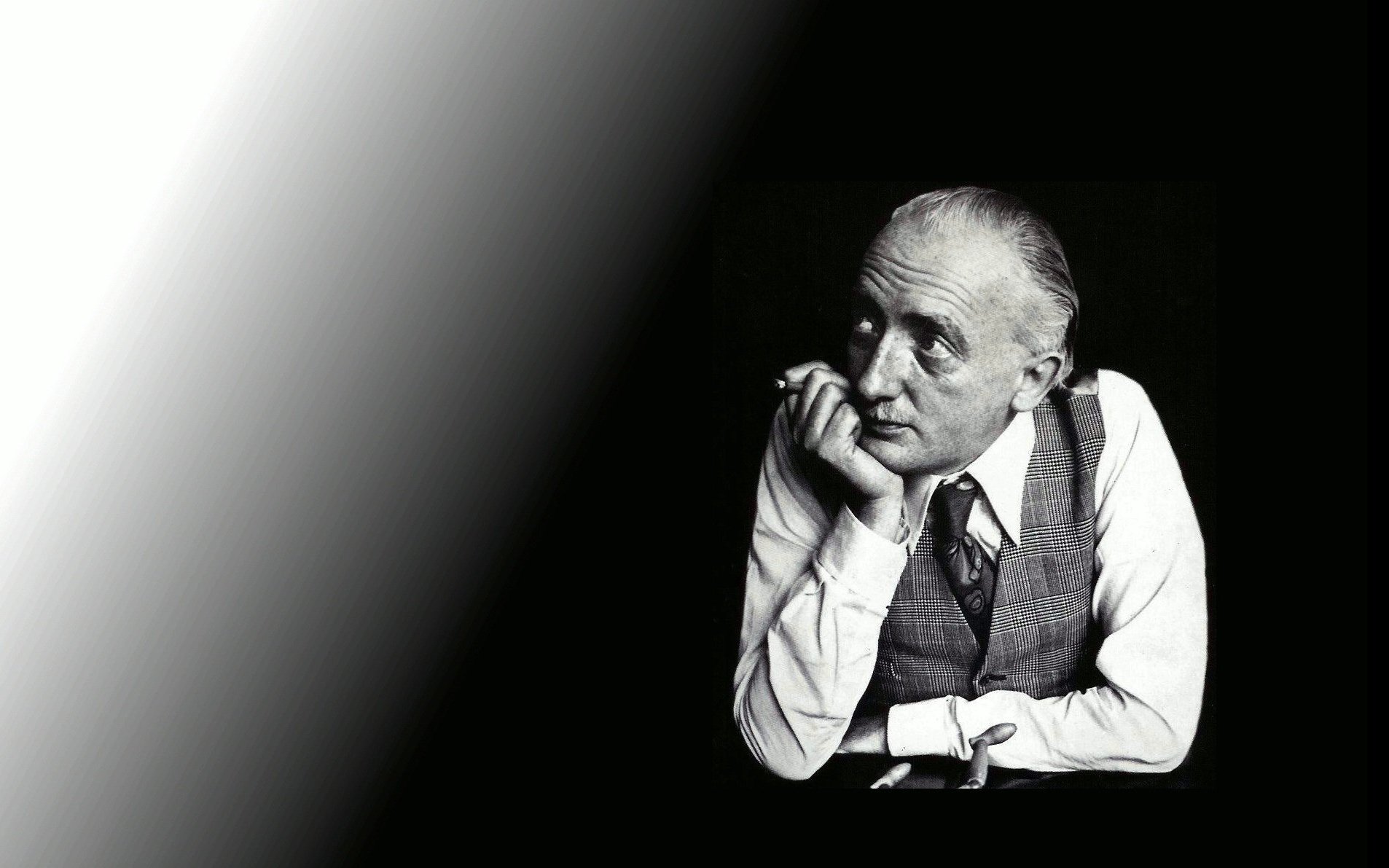

Seán Ó Riada

Ó Riada's Vision

In the winter of 1964, in what used to be Irish teacher Domhnall Ó Ceocháin’s house in Muirneach Bheag, Cúil Aodha, about 50km from the city of Cork, a raggle-taggle group of singers gathered in a small sitting room facing the keys of a modified Steck pianola. The hands on the keys on this inauspicious occasion were those of composer Seán Ó Riada. But this would be the first of many such musical evenings that would transform the musical landscape of this area and for some of those present mark the beginning of a seven-year quest that would transform their musical world.

If through his experimentation with Ceoltóirí Chualann and his wider involvement with the traditional idiom Ó Riada created a template which has lived on through many artists and groups, his actual engagement with the keepers of the Irish tradition was however to be tragically cut short. By the time of his death in 1971, Seán Ó Riada had formed close bonds with many in his adopted community, but in particular the members of the Cúil Aodha choir (Cóir Chúil Aodha), which he founded.

Ó Riada’s initial aim was the establishment of a choir that would perform a mass he intended to write which would be performed in the local village church. He had the backing of the local curate, an tAthair Donnchadha Ó Conchubhair, and the tacit knowledge that a choir singing in their own linguistic vernacular would garner approval in the post-Vatican II environment. In this regard he would prove to be ahead of his time.

In Cúil Aodha he found the raw materials necessary to the task. Those present that evening could hardly be regarded as trained singers in the generally accepted sense of that term; they were, in essence, a random collection of individual voices most of whom were highly regarded locally as performers of traditional songs. All were native Gaelic speakers and some were experienced composers and performers in the public sense, having attended competitions such as the Oireachtas, singing songs from the local sean-nós repertoire as well as newly written lúibíní (a dialogue sung by a duet in the sean-nós style), amhráin saothair (work songs) and so forth.

The sound produced by this gathering of native voices singing for the first time in unison would necessarily have had a raw edge to it, but this of itself may have been the source of its appeal and efficacy, particularly to those directly participating in the choir. The notion of a thicker, stronger weave of sound coloured with their own musical fingerprint would, I believe, prove influential both in the continuation of the choir and in their choice of material.

Ó Riada’s arrival

The arrival of Ó Riada to this remote corner of Ireland in the 1960s was opportune. In Cúil Aodha at the time he found a society under considerable economic stress with no local industry to speak of and a population whose younger generation, though brought up in an environment of traditional values (which included a latent religiosity and arguably a linguistic and cultural insularity), were beginning to see and move outside it.

It was a society, to those within it, whose cohesion was fraying at the edges under pressure from forces much more powerful than it could on its own muster. Many of the younger singers were toying with the showband phenomenon and habitual speaking of Irish was on a steady decline. Ó Riada’s arrival, however, heralded a deliberate re-activation of the local music culture. This involved an intensive trawl of old collections, the tape-recording of venerable singers such as Pádraig (Peaiti Tadhg Pheig) Ó Tuama, the learning and adaptation of archive material, and then the exposure and celebration of these renascent musical artefacts in public performance, not only in the church but also in halls throughout the country.

Cúil Aodha would eventually come to be seen as the last step in Ó Riada’s cyclic development as an artist; a journey that brought him from a familial traditional-music background, through the explorations in serialism of his nomoi compositions, and back again – transformed by the spectacular success of his film music settings for Mise Éire and Saoirse to that of a public figure experimenting with and extolling the virtues, as he saw it, of a native, ancient and noble music culture and language. For some, particularly those who looked to Ó Riada as the key hope for the development of Irish art music, this atavistic migration would come to be interpreted as a catastrophic failure and betrayal of his true gifts.

For the formerly solo singers of Cúil Aodha, however, who were mostly drawn from small farming backgrounds, his philosophical and musical about turn would be a cultural and economic renaissance. In time, Ó Riada’s reputation and panache secured new industries for the region, and gave its music culture a platform and confidence it had never before experienced. This confidence also fed off the other sources, most notably the re-emerging nationalism evoked by the Northern troubles and a latent re-inscribed sense of nationhood as prescribed by Douglas Hyde and the Gaelic League.

These were not difficult energies to harness, since the regions surrounding Cúil Aodha had, a half-century earlier, been hotbeds of guerrilla insurrection prior to the establishment of the Irish Free State. A cultural re-enactment of the sort promulgated by Ó Riada found easy reception in the fertile ground of a place which Republican ideologue and martyr Pádraig Pearse had called ‘the capital of the Gaeltacht’ in An Claidheamh Soluis in 1908.

A new song

After Sean Ó Riada’s untimely death in 1971, the choir continued under the direction of his then seventeen-year-old son Peadar and it continues to this day. Domhnall Ó Liatháin, well known in Cúil Aodha as a local poet and retired teacher, has a longstanding association with the choir. He was one of the initial members and was appointed as treasurer of the choir by Ó Riada in the early days. But it is Ó Liatháin’s role as editor and scribe of the choir that shows his greatest importance and talent.

Ó Riada’s death cast a pall over the little village in which he lived and one can imagine the blow it must have been to his colleagues who had for so many years seen him as a leader and guide. A year or so after his father’s death, Peadar called a choir practice to begin work on a new song, for which the initial point of departure was a tape recording. According to Ó Liatháin, in an interview I carried out with him,

We were gathered in the Ó Riada house – Maidhci Sullivan was there as were Jeremiah Riordan, Eugie, myself … Domhnall Eoini and some other of those lads. There may have one or two of the Ó Lionáirds present but they were young and may not have had much to do with things as they were; maybe they were in the kitchen fooling around with the Ó Riada children – it’s hard to tell. But we were inside there … and Peadar had this tape and he put it on and on it was a man, if my memory serves me correctly, whose name was Domhnall Ó Buachalla. … You could recognise from the tape that his was an old voice. [Peadar] told us that this was a tape that his father had collected from the man in question and he played us a song from it, and I think that the verse that affected me most was

Gile mear sa seal faoi chumha

Gus Éire go léir faoi chlocaí dhubha

Suan ná séan ní bhfuaireas féin

Ó luadh i gcéin mo ghile mear.

…I didn’t recognise the air at all myself, it was a very muffled recording. But Maidhci and Jeremiah did recognise it… The next thing that happened … was that Peadar gave it to me saying that we could make a song from this melody.

Ó Liatháin did recognise that one of the two verses on the tape came from a poem of Seán Clarach Mac Domhnaill (1691–1754), ‘Bímse buan ar buairt gach ló’ (I am forever grieving every day) which was a familiar text to those studying Irish poetry in the 1940s and 50s. It concerned the exploits of Bonnie Prince Charlie and his attempt to take the British crown in the 1700s. Although the 24-year-old Prince Charlie’s forces were defeated comprehensively in April of 1746, this daring episode of Scottish history was and still remains the stuff of myth, romance and legend.

The second verse on the tape has no known written origin but it would subsequently become the last verse of the new construction. A further complication enters the frame, however, as Ó Liatháin decided to incorporate another of Seán Clarach’s poems into his construction; this composition, titled ‘Seal do Bhíos im’ Mhaighdin Shéimh’ (Once when I was a gentle young girl) would provide the opening verse for the finished song. Ó Liatháin remained modestly guarded as to the process of selection:

I had no plan whatsoever except that I … would take the most beautiful verses … the verses that were… sort of universal as you might say. There really wasn’t any difficulty because it was kind of clear that this was the thing you would do…. The words and lines were very nice in the verses that we chose, but … Seán Clarach really was a superb craftsman as regards metre and so forth and you couldn’t really find a bad verse where the metre would not be spot on.

There were also some actual textual changes, most notably to the chorus. In its original form it read:

Isé mo laoch mo ghile mear

Isé mo Chaesar gile mear

Ní bhfuaireas fhéin aon tsuan ar séan

O chuaigh i gcéin mo ghile mear.

It would become:

‘Sé mo laoch mo ghile mear

‘Sé mo sheas ar gile mear

Suan ná séan ní bhfuaireas fhéin

Ó luadh i gcéin mo ghile mear.

Although the poem dealt with a political dimension not immediately relevant to the then Irish political situation it nevertheless communicated to a thawing nationalist Irish psyche.

Its layered intertextuality would have been transparent to the choir membership. Their rich imaginations, born of an upbringing steeped in oral retellings of these folk tales, and their closeness to the national struggle, uniquely equipped them to draw a very real political relevance from the song’s deeply allegorical trove.

And immediately it began to occupy an important place in the choir’s publicly performed repertoire. Prior to its arrival the choir habitually ended a night’s song in public performance with a humorous song – ‘Scoil Bharr d’Inse’. It would soon be usurped by what was now being called ‘Gile Mear’ – a Cúil Aodha song! It was accorded an additional life when its air started to be played at funerals as the coffin made its journey shouldered from the altar to the hearse. It in effect became the Cóir Chúil Aodha anthem.

Domhnall Ó Liatháin explains:

As time passed it became the song that would be sung at the end of the night and people really loved it. You’d meet people all over the country and they’d be saying …, “Who wrote it? That was a great song,” and … we used to always say, “This is how it was always sung in Cúil Aodha” which was not right because it wasn’t… it wasn’t sung in Cúil Aodha you understand… Well the thing about it was that it was Gaolach [Gaelic in a tribal as opposed to a linguistic sense] and nationalistic and manly and that it consisted of all these things. … the melody itself … had a marching rhythm, there was the sense of … referring back to times of heroism and triumph in Ireland and … I suppose it fitted into the atmosphere at the time since the situation in the North was quite troublesome. And then Ó Riada himself was dead and there was… there was a certain sadness to that period…

It is interesting to reconsider at this point the mood in traditional Gaelic circles after Ó Riada’s passing and to note that for many who inhabited Ó Riada’s musical world during the sixties and in subsequent years, his death marked a breach of incalculable proportions. In ‘Mo Ghile Mear’ the choir mourned the loss of a great chieftain and also the loss of a shared vision. It is not difficult to suggest that the hero in ‘Mo Ghile Mear’ – when sung by Cóir Chúil Aodha – was Ó Riada himself, prematurely taken from his people and with him their dreams of a civilisation restored. According to Ó Liatháin:

…I saw Ó Riada as a window you understand, who opened for us a light, a vision, a view of the old Gaelic life as it used to be. And he guided us as to how we might revive it again and put it on a sound footing. That was the vision which Ó Riada had … Maybe it was an unattainable vision, perhaps it could not have been put in place in its entirety, but a good deal of it could. This was very evident in Ó Riada’s music and there’s no doubt that we were following his quest with the song ‘Sé mo laoch mo ghile mear…’.

In the light of a post-revisionist and post-Good Friday Agreement Ireland (no matter how tenuous), it is difficult not to level the charge of political naivety against this vision of Irish life, with its obvious historical atavisms. Nevertheless, however easily the forceful surge of nationalistic sentiment stimulated by events at the time can be processed now as historical fact, for the people who lived through those times the reality of the emotion it generated cannot be underestimated – nor can the re-animated self-confidence of the dormant Gael, even if it sits uncomfortably in our contemporary mindset.

Ó Riada palpably contributed to this effect upon people of all walks and certainly on his colleagues in Cúil Aodha. The deliberate construction of ‘Mo Ghile Mear’ as a tool of this vision bears this out. For the marginalised Irish-speaking and traditionally-based communities – such as Cúil Aodha – music and oral culture had for generations been a sustaining force. In Cúil Aodha’s encounter with Seán Ó Riada, it reached, for many, a new majesty, an inspiring apogeal orbit.

Published on 1 July 2006