Judith Ring at a rehearsal of To pull an eerie twist. Photo: Benedict Schlepper-Connolly.

No Strategies

I’m arched over the grand piano, the lid is off, and my hands are flat out, furiously hitting the strings. I can hear the blood in my ears; I increase the speed of the drumming so as to keep the air ringing with roaring harmonics. My left hand is suddenly rigid, stopping the string at the node, my right hand striking the a key on the keyboard with all my weight and accumulated energy. There’s no repose; the speakers at the top of the room spill out a wash of subterranean piano sounds, as if I caused all the pianos in the world to resonate in sympathy with my exertions. Memories from recording Judith Ring’s Panoval for piano, violin and playback; such a totally corporeal experience, and such totally corporeal music.

Another memory: Ring and I are seated in the living room of her rented house in York, England. She’s moving back home to Dublin tomorrow after nearly four years of study here, and the room is bare except for a few cardboard boxes. We sip black tea (she has no milk) and talk about Mouthpiece, a piece for female singer and playback. She composed the piece in 2006 for Natasha Lohan, and the process began in the recording studio with Ring recording eight sessions of Lohan’s whispers, shrieks, breaths, ululations, improvised melodies, whimpers and groans as well as straight, single notes. The usual next step for Ring would have been to change the sounds using a computer, to artificially thicken, reverse and deepen. But her ears wouldn’t let her. ‘As I tried to transform her voice,’ she says, ‘I experimented with some samples just as they were, and I got incredible results. I decided, well, I’ll restrict myself. I won’t process any of the samples because her voice is already rich enough….’

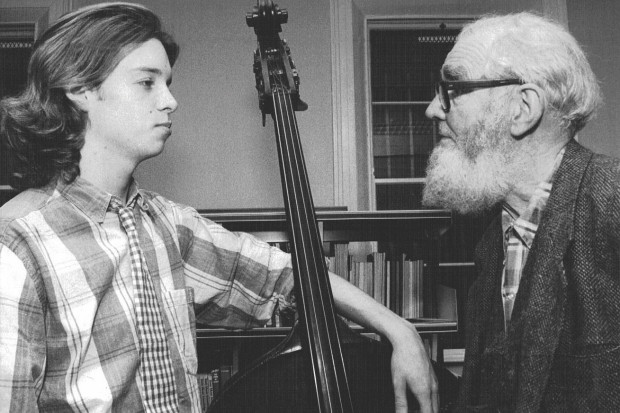

Mouthpiece set Ring on a path. She has followed it up with a number of works for playback and musicians, each made with the same intuitive, very physical process. The impetus often comes in the form of a musician or group of musicians with a distinct performance personality; Natasha Lohan is one, others include the singing cellist Laura Moody, the Dutch Adapted Viola player Elisabeth Smalt and the Irish ensemble Concorde. Ring gets in a room with her musician – only ever one at a time – and she starts recording. There are no pre-conceived ideas, no strategies. A feedback loop is set in motion: a sound is created, a change is suggested – ‘higher‘, ‘harsher’, ‘more pressure’, ‘lighter’, ‘darker’ – and more sounds come to life. Raw material is generated from actions, not plans.

Ring then isolates each sound she has recorded, preparing hundreds of individual audio samples one by one. This work takes hundreds of hours. And all the time she’s listening. By the time she gets to create the playback part of the piece, compositional ideas have begun to flower. ‘The sounds suggest the piece to me,’ she tells me. ‘I can only conceive a piece when I’ve heard the material.’ When working on Whispering the Turmoil Down, a piece for bass clarinettist Paul Roe and playback, Ring felt that her lush recordings of clarinet multiphonics needed space to breathe – she let these sounds alone make up the entire fabric of the playback part. She then felt that the part for live bass clarinet could only contain collections of melodic fragments: a kind of gentle filigree.

‘I guess there are more analogies with the way painters work,’ says Ring. ‘You’re working with colour and mixing colour…. I’m working with a canvas, putting the colours on and mixing the sound. So that it blends together, or sticks out slightly… like a Jack B. Yeats painting, the way his paint comes off the canvas.’ Ring is herself a painter, albeit a modest one. ‘[When I compose] I have a canvas of a computer screen – unfortunately,’ she laughs, ‘I’m placing the sounds, and I’m listening very, very carefully, rather than doing it visually – that’s the only difference really.’ She would prefer to work her audio samples with her hands, if such a thing were possible: ‘I’ve often thought, “I just want to pick these sounds up and put them against each other.” It would be a dream come true to be able to do it with my hands.’ It doesn’t surprise me to learn that a composer who would talk about a piece in terms of ‘dark greens and browns’ would colour-code the audio files on her computer such that the screen might resemble some kind of visual art. ‘You run out of colours very fast,’ says Ring, despondently.

Ring’s working method – where the rawest material always points the way – is not as present in the study of music composition at universities as it could be. Ring’s work is first and foremost with the pulse in the arm that glides the bow over the string. She does not begin with a highly abstract, one-dimensional idea of that sound in notation. Her process can be described as truly experimental, in the sense of Charles Ives: open, aware, conscious, hopeful. ‘I think it’s a valuable educational tool to work like that – to get a student to be with a performer and explore an instrument,’ says Ring. I agree with her: composition is about making intellectual decisions, for sure, but you can’t lead an army if you don’t know how it feels to load a gun.

Listen to more of Judith Ring’s music on Soundcloud or watch our video of Ring attending a rehearsal of To pull an eerie twist.

Published on 1 February 2011

Garrett Sholdice is a composer and a director of the record label and music production company Ergodos.