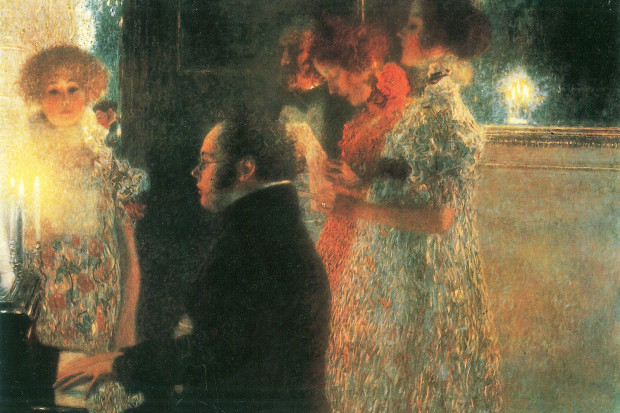

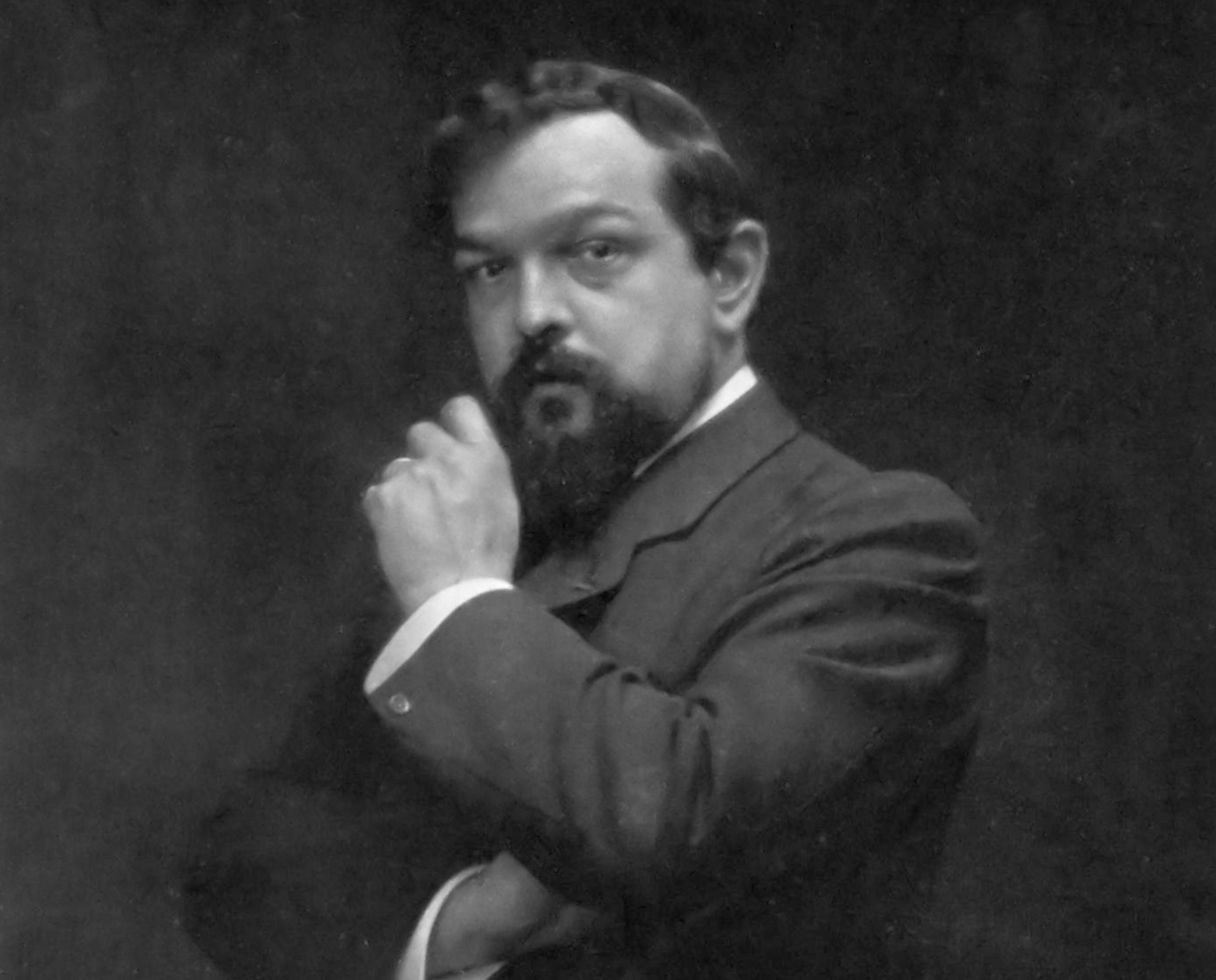

Claude Debussy in 1908 (Photo: Otto Wegener)

No Hint of Bad Taste

I’ve been intrigued by Debussy ever since reading a crazy book by the French composer/critic André Hodeir called Since Debussy, which not only cracked Debussy up as the greatest composer practically since time began, but also rubbished a good deal else, especially in the German tradition, while setting up a composer I’d never heard of called Jean Barraqué as a genius comparable to Beethoven.

I was a first-year music student at the time, and to me Debussy was still the composer of Clair de lune, the Golliwog’s Cakewalk, and perhaps, on my more adventurous days, La Mer. The idea of him as a life-changing genius was quite outside my scope, especially when it came with the need to regard most of what I actually knew and loved as more or less dispensable. I then came across an article by a French composer I had heard of, Pierre Boulez, saying much the same as Hodeir, but with more authority and without the need to write off everything German in the same breath.

Oddly, though, the key work for Boulez was one I didn’t then know, a rarely performed ballet called Jeux. As an undergraduate I was quite familiar with the temptation to talk up rarities just to be different. But Boulez’s motive was surely less crude than that. In Jeux he found a new kind of musical form that involved what he called ‘instantaneous self-renewal’, which was something essentially modern that he saw as a precursor to his own extremely complex kind of serial technique. It helped, of course, that Debussy was French, not Austrian like Schoenberg or Russian like Stravinsky. But what struck me was the yawning gap between the popular Debussy and the idol of the impenetrable avant-garde.

The only thing that mattered

The apparent contradiction was present in Debussy’s own mind from the start. There was hardly any music in his background, yet thanks to a cultivated aunt who arranged for him to have piano lessons and a more serious teacher who claimed to have been a pupil of Chopin, he showed enough talent to be admitted to the Paris Conservatoire when he was ten. There he studied piano, theory, composition, the whole academic and technical package, and long before he graduated with the coveted Prix de Rome in 1884 he had rebelled against nearly all of it. In a conversation with his former composition teacher, Ernest Guiraud, a few years later he made fun of the textbook rules of harmony, the whole idea of the major and minor scales, the tyranny of the barline, and the heavy orchestration and vocalising in opera. For him the only thing that mattered, he said, was his pleasure. Yet he was a keen Wagnerian long before he ever saw any Wagner on stage, while sensing the danger of Wagnerism to French music. He fought all his life, not always successfully, against its influence.

His life, like his music, was rich in contradictions. He loved fine food and drink and expensive luxuries in general, but was usually broke. He had a sensual nature and a strong libido and went to bed with several, probably many, women. But his two marriages and one settled extra-marital affair (not counting a long adulterous affair while he was still a student) were mostly torture for his other halves, because he never concealed the fact that his music meant more to him than their feelings. He had the dangerous faculty of mistaking sexual passion for lifelong devotion, as his gushingly sensual letters to his first wife, a model called Lilly Texier, demonstrate all too clearly, since soon after receiving a batch of them a few months before their marriage, she arrived to find him in bed with another woman. The letters are saturated with moon-and-June phrases that he would never have stooped to set to music. He was also, alas, a natural liar. He lied transparently to close friends about his aborted engagement to a singer they knew well, and he lied to his publisher about the progress of contracted works. Nothing in the end mattered except his music; but that mattered so much that he could spend days on end refining small details of orchestration or piano writing. Hence the need to lie about everything else.

There was also his penchant for café life and the company of what the French call the marginal, or we today call ‘alternative’. This is the world of Toulouse-Lautrec and Erik Satie; life on the cultivated edge of the dark precipice, a world where great artists rubbed shoulders with absinthe addiction, prostitution and other nameless horrors of the road and the cellar bar. In fact, though it certainly had its seedy side, this world was extremely cultivated in its own way. Here Debussy met theatre people, playwrights, poets, actors, diseurs, as well as painters and fringe artists like the shadow-play designer Henri Rivière, or the chansonnier Narcisse Lebeau. He could discuss Schopenhauer with the Symbolist poet Jean Moréas, or Wagner with practically anyone. And – for him a distinct advantage – there were not too many musicians, at least not of the Conservatoire variety. At the famous Chat Noir and other bohemian establishments he met writers who would provide him with ideas and even libretti for operas that he never quite got round to composing, but which must have fed into his mental world in all kinds of enriching ways.

No interest in grammar

Perhaps the most obvious of these is the sense of not being beholden to the conventions of musical tradition. Talking about Wagner with a Symbolist poet, you’d hear little about symphonic development or the resolution of discords, but a good deal about what Charles Baudelaire, after hearing Wagner conduct, had described as ‘the idea of a soul in motion in a luminous medium’ and ‘an ecstasy formed out of sensuality and consciousness.’ Debussy was not normally one for fine phrases, but he knew all about atmosphere and states of mind, and he seems to have set out to write music that reflected these conditions. Thematic organisation and the harmonic grammar that kept it on track – like grammar in any spoken language – no longer interested him. Instead he cultivated what he himself called ‘images’, single ideas that could be explored in depth, in the way one peers into a deep pool or walks in a forest.

Some of these images are visual and share their subject-matter with Impressionist painting. Debussy, like Monet and Whistler, was fascinated by water, which so to speak moves without changing; or rustling leaves, or even, in one of his greatest piano works Cloches à travers les feuilles, the combination of leaves and bell sounds, a mixture of the seen and heard that only music can create.

But not all his images are visual. Sometimes he will take a line of poetry, like Baudelaire’s ‘Les sons et les parfums tournent dans l’ai’ du soir’ (sounds and scents mingling in the evening air), or Charles Favart’s “Le vent dans la plaine suspend son haleine’ (the wind in the plain holds its breath), and imagine a musical equivalent. Or he will remember the sights and sounds of places he had never visited: southern Spain, or Capri, or Indonesia, a peculiar form of memory that French musicians are particularly good at. Later he starts to abandon actual titles, while still writing music that might have had them. In the two books of piano preludes he notoriously puts the title at the end of each piece; and then, in the Études and the late chamber sonatas, he drops them altogether, though one still feels he might not have done.

Slice a single chord sequence

What kind of music went with these ideas? Inspired more by atmosphere than argument, Debussy plundered the vocabulary of Romantic music, the chords and rhythms and melodic figures that were the bread and butter of Schubert and Wagner, and older French contemporaries like Gounod or Massenet or the Belgian César Franck. But he gave them a new context. He would slice a single chord sequence out of Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde and repeat it in an almost minimalist way to capture the atmosphere of a Verlaine poem. He would take a run of the mill dissonance like a seventh or ninth chord – a lovely sound but one that theory requires to be resolved into a consonance – and not resolve it, but study it, repeat it in streams, sometimes with slight variations but not ones recognised by the textbook. His so-called Hommage à Rameau in the first book of piano Images is a brilliant example. It has hardly anything to do with the eighteenth-century composer Rameau, but is full of the most wonderfully beautiful chord sequences, exquisitely voiced (spaced under the hands: Debussy surely took hours getting such things right), yet never remotely grammatical in any academic sense.

One other source that encouraged, perhaps even inspired, these methods was the music of the Javanese gamelan orchestra and of the Annamite (Vietnamese) theatre that Debussy encountered at the great Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1889. The gamelan music followed modes that created an intricate and fascinating web of polyphonic sound within a motionless harmonic ‘field’; the more violent Annamite music seemed to follow some obscure logic that led many critics to describe it as cacophony and even sympathetic listeners to admit that they could make neither head nor tail of it. But for Debussy such strangeness was something to investigate. ‘Do you remember,’ he wrote years later to his poet friend Pierre Louÿs, ‘the Javanese music that contained every nuance, even those one can no longer name, in which tonic and dominant were no longer anything but empty ghosts for use on naughty little children.’ And the Annamite theatre he called ‘embryonic opera’: ‘no more special theatre, no more hidden orchestra. Nothing but an instinctive need for art, needing ingenuity to satisfy; no hint of bad taste!’

Debussy’s insistence on beauty and pleasure has tended to encourage the assumption that his music is too nice to be important or even serious in the way that, say, Beethoven or Brahms are serious. One might even think: I like this, so it can’t be modern. But in reality his individual methods had an explosive effect on twentieth-century music comparable to that of Stravinsky and Schoenberg, without it seems in any way jeopardising his popularity.

His influence is everywhere to be seen: in jazz, in film music, in the so-called minimalism of Steve Reich and Philip Glass, even in the tinkly rubbish (not of course his fault) that assails us as we wait in a telephone queue. Through the French composer Olivier Messiaen, who copied and extended his chordal and melodic ideas, his procedures (if not his style) reached the postwar avant-garde dominated by the Messiaen pupils, Boulez and Karlheinz Stockhausen. There is hardly a single composer living today who would not regard Debussy as a crucial study for his or her own work. Whether this would have amused Debussy himself is an unanswerable question. In abandoning the methods he studied in the Conservatoire, he simply had to invent his own technique as he went along, and in this respect as well he set a precedent for twentieth-century composers as a tribe. The fact that he managed this without alienating his more conventional-minded public is not the least extraordinary thing about this extraordinary artist.

Published on 19 April 2018

Stephen Walsh is an Emeritus Professor of Cardiff University, and was previously deputy music critic of The Observer. A well-known broadcaster, he now reviews for the website theartsdesk.com. His books include a major biography of Igor Stravinsky and a study of the Russian Five. His latest, Debussy: A Painter in Sound, was published by Faber.