myTunes and i

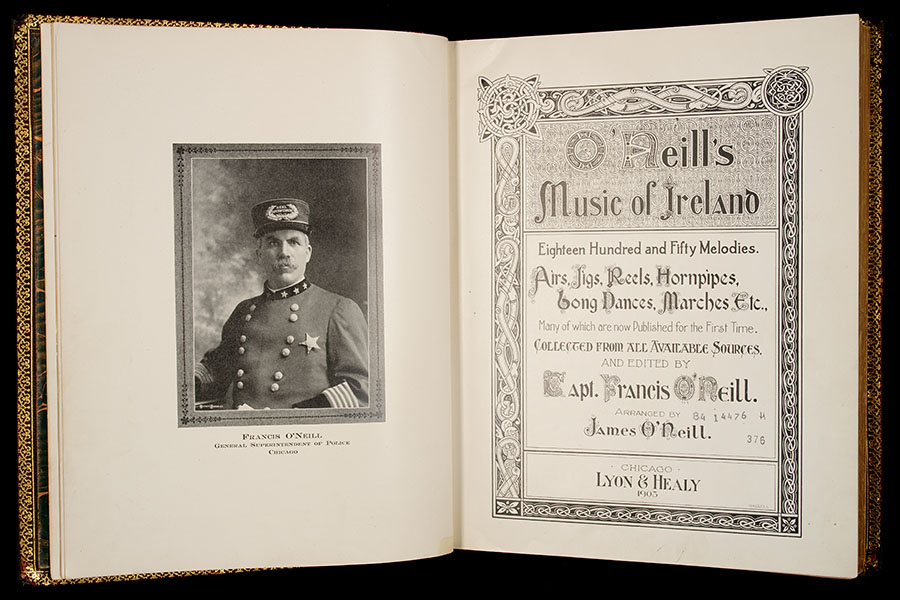

The positive impact of the O’Neill collections of tunes, the most significant of which was published one hundred years ago this year, is widely acknowledged, but the focus on written collections in traditional music can obscure the intangible qualities of tunes – and musicians’ relationships to tunes.

Tunes are musical goods that we tamper with, the focus of our temporary experiments with the aesthetics of this music, with our own technique, with the challenge of finding musical unity in playing sixteen bars three times over. Tunes are patterns that we arrange, undo and reassemble. Sometimes musicians will erupt in the middle of a performance with a rush of variation and ornamentation, only to then quickly talk the tune back down and play it through straight before moving on to another – almost as if trying to innocently leave it back as they found it.

Some tunes in a repertoire are always satisfying to play, providing a renewed artistic and technical experience. It is fascinating how fiddle player Kevin Burke still performs, and records, tunes such as ‘Pigeon on the Gate’, ‘Cottage Groves’ and ‘Maudabawn Chapel’ decades after he recorded them so definitively in the 1970s and early 80s.

In an O’Neill book from 1915 containing 400 Choice Selections Arranged for Piano or Violin the enticing subtitle reads ‘Most of them Rare; Many of them Unpublished’. This search for the rare tune is still a part of traditional music culture today. A tune no one else knows, a version of a tune no one knows, a novel restructuring of a tune, an exceptional musician few have heard of – this is the kind of select knowledge that traditional musicians take pleasure in gathering. New sources are just important as new tunes. Although it’s unlikely that O’Neill’s tunes have been recorded or played regularly, musicians will today look to DVDs, CDs, new books, older books, television programmes, radio and concerts, waiting for that moment when they hear a tune that they know they just have to have.

Because of the oral form in which the style and repertoire of this music is passed on, strands of the music will fall by the wayside. As flute player Harry Bradley recently remarked on Áine Hensey’s The Late Session, thousands of tunes have been lost or forgotten over the years. To rediscover, uncover, overhear or reinvent one, therefore, is like finding ‘a hidden transcript from the oppressed’ (to quote Michael D. Higgins out of context). But finding tunes to play can be a two way process. As Bradley observed, tunes that for years you may have discounted as being ‘hackneyed’, or simply not being for you, can one day spontaneously renew themselves in your mind.

The comings and goings of tunes is interesting to watch, though often elusive process. Did Frankie Gavin’s playing of ‘The Golden Eagle’ on the Bringing it All Back Home CD in the early 1990s inspire everyone to start playing that tune in sessions, or were they all already playing it because of Sean Keane’s earlier recording? Take Michael Goldrick’s syncopated reel, which could be heard everywhere in sessions after when he released his CD in the late 1990s. Where can it now be heard? In twenty years, will it be played at all?

Flute player and composer Emer Mayock recently mentioned on Peter Browne’s Rolling Wave radio programme that in order for a new tune to have a hope of becoming part of the repertoire, she felt it had to be played over and over in the musical food mixer that are sessions so the edges could get knocked off it. Then it may slide anonymously into the repertoire of musicians. The obvious question, then, is why can’t traditional music composers write tunes that automatically go into the traditional music repertoire? Why is the process of amendment necessary? Part of the answer is that while composers could indeed write tunes that would sound ‘old’ and might not look out of place in an O’Neill collection (although as Caoimhín MacAoidh has pointed out, James O’Neill wrote some of the tunes that went in the O’Neill collections!), that is not necessarily what a traditional musician is looking for. It may surprise those to whom traditional music all sounds the same, but traditional musicians actually want difference, not sameness. They also want something that ‘falls well’ on their particular instrument. Harry Bradley explained that he is always looking for some ‘rhythmic potential’ that will offer him various avenues in performance, while others may be looking for a particular turn or phrase that marks it out as distinctive. Consider fiddle player and tune composer Charlie Lennon. His ‘Ríl an Spidéal’ and ‘Kilty Town’ reels, both firmly established now as ‘traditional’ tunes, would still leap out as being distinctive at any session.

It is also the case that a traditional music composer will often naturally compose on their own instrument, and it follows that other instruments will then have to adjust a piece, however slightly, to suit themselves. By putting a new tune into the ever available session mixer, a version will likely emerge that is ready minted to suit most instruments.

Some suggest the number of newly composed tunes suitable to the traditional music aesthete could be counted on two hands. But do we know for sure whether we are playing newly composed tunes or not? Martin Hayes plays the ‘Kerfunken Jig’ on his CD The Lonesome Touch, but, so common has it become that there is no mention that it was written by the Belfast flute player Hammy Hamilton. The actual title of the tune is the ‘Kerfunteun Jig’, named after a place in Brittany and written around 1983. Hamilton taught it to two flute players – Marcus Hernon (who recorded it on tape with his brother P.J. in the 1980s) and Conal Ó Gráda who began teaching it at classes – and after that the history of its spread is not traceable. Twenty years later and it has been recorded over thirty times, to the extent that the majority of people playing it would probably not know the name of its composer. This is a good indicator of how fluidly this music moves around. As the Director of Music in RTÉ, Niall Doyle, often pointed out in his championing of new music by Irish composers, old music had to be new at some stage!

Published on 1 May 2007

Toner Quinn is Editor of the Journal of Music. His new book, What Ireland Can Teach the World About Music, is available here. Toner will be giving a lecture exploring some of the ideas in the book on Saturday 11 May 2024 at 3pm at Farmleigh House in Dublin. For booking, visit https://bit.ly/3x2yCL8.