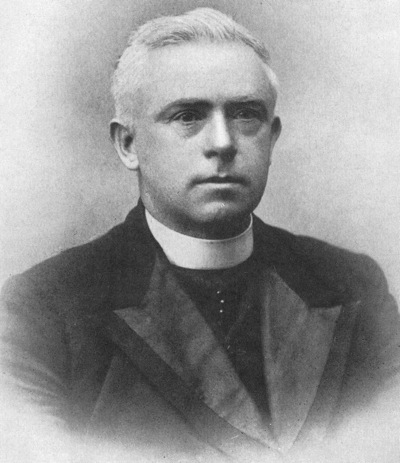

Richard Henebry

The Musical Priest

My wife Deirdre used to visit the accordion player Sean O’Neill back in the 1970s, and when Sean would take up the accordion to play a few warming-up notes, his Golden Labrador dog would begin to howl mournfully and look reproachfully at his master. The dog would have to be put out of the room, and would go resignedly, being well used to it, so as Deirdre and Sean could get down to playing some tunes without canine accompaniment. No doubt the dog had a good ear: the accordion in question was one of those big red Paolo Sopranis, notorious for being a little or more than a little out of tune with themselves.

I am reminded of a passage in Father Richard Henebry’s A Handbook of Irish Music. ‘There is by me now a cocker pup of a few months old,’ says Henebry, ‘who listened to my playing of the Binsin Luachra (The Little Bunch of Rushes) with a comic air of the keenest and most intelligent appreciation, and even turned his head askew whenever I played the trilled Irish C natural that occurs remarkably in that melody, in order to denote that something new and unexpected had come within the range of his observation, as is the manner of dogs.’

Richard Henebry was a remarkable figure. Born in 1863 to an Irish-speaking family in Mountbolton near Portlaw in County Waterford, he styled himself Risteárd de Hindeburg in Irish: he was, it seems, descended from the Norman Philip de Hynteberge or de Hindeberg, lord of the manor of Rath in County Dublin in 1250. He was ordained at Maynooth in 1892. Subsequently he was recruited by the Catholic University of America at Washington, DC to fill their new Chair of Celtic Studies. The appointment was not without controversy: the University, founded in 1887, was poorly endowed, and the Chair had been funded by the Ancient Order of Hibernians. It was, indeed, called ‘The Murderers’ Chair’ by some. Henebry wished to begin his duties immediately, but the University sent him to Germany for two years, where he earned his PhD before taking up his post in 1898.

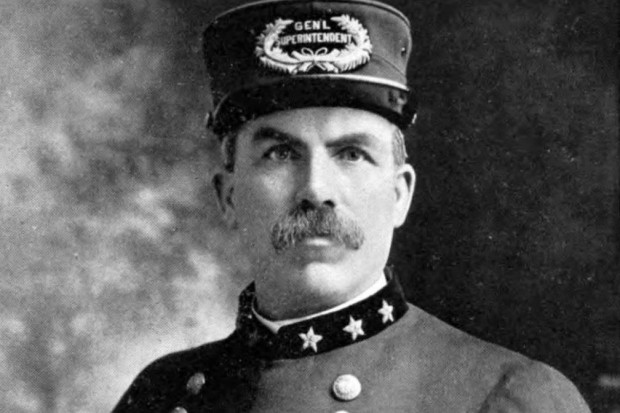

He rapidly established himself as a force in Irish-American politics, becoming President of the Gaelic League of America. He had been appointed Professor of Celtic on a three-year contract, continuance and tenure to be determined on its expiration. Once more he found himself the subject of controversy. When the three years ended, he was not reappointed. His supporters maintained that he had been dismissed because of his political activities, while the university, backed by the hierarchy of the Catholic Church in the person of the University chancellor, Cardinal Gibbons, alleged that he had not fulfilled his duties. Henebry, who suffered from TB all his adult life, had in fact been ill during his term. Despite an energetic campaign mounted on his behalf, the decision of the University stood. It was possibly in the aftermath of this setback that he first became acquainted with Francis O’Neill, who coincidentally was appointed Chief of the Chicago Police in the year of Henebry’s disappointment. ‘Among the happiest days of our life,’ says O’Neill in his Irish Minstrels and Musicians, ‘were those in which the genial doctor [Henebry] favoured us with his music at our residence in Chicago in 1901, playing solo or in concert with the Irish-American pipers, fiddlers and fluters whom he subsequently immortalized in current literature.’

Henebry returned to Ireland in 1903 and acted as chaplain to various institutions in Waterford. He was active as ever in the Irish-language movement and was involved with the establishment of the Irish College at Ring in 1909, in which year he became Professor of Irish at University College Cork. Among his acquaintances were Irish patriot Roger Casement and founder of the Gaelic League Douglas Hyde, and for some years Henebry was a vociferous critic of the work of Pádraig Pearse, whose plays in Irish he compared to ‘the frivolous petulancy of latter-day English genre scribblers, their utterance… the mincing of the under-assistant floor-walker in a millinery shop.’ The issue was a matter of perceived ‘authenticity’ versus innovation: Henebry espoused the use of the ‘Gaelic’ alphabet, while Pearse, wanting Ireland and its language to be part of a modern Europe, promoted the Roman alphabet. Similarly, Pearse thought that Irish music should be the basis of a national music along the model of a Bartók or Kodály; Henebry was passionate in his advocacy of traditional music as an art-form in its own right, and not raw material for a supposedly more sophisticated form.

Henebry’s thesis, as outlined in A Handbook of Traditional Music, published posthumously in 1928, is based on his assertion that ‘human and animal music are essentially the same.’ ‘The lark,’ he observes, ‘sings dance music, and specifically with the rhythm and action of a reel, and can beat regularly for astonishing lengths at a time.’ Real music, i.e. that which comes from absolutely conservative principles, is ‘natural’; modern music is artificial and contrived, and out of tune with the human scale, which ‘instead of having seven intervals… is rather like the spectroscope with its endless lines of varying colours and intensities, and with certain supernal positions that are entirely unknown to the moderns because the notes of their scale fall between them.’ He claimed that the Irish language was essential to the production of Irish music:

I have noticed in a district where a National School has substituted English for Irish in the last ten years, the young girls, from their non-use of Irish speech, have entirely lost the Irish singing voice. For this habit of English has a physical effect on the speaking organs, and destroys the full, soft, and mellow Irish voice so necessary for singing, and the acquisition of new ideas has ousted the Keltic outlook, and with it the subjective outlook from which Irish music sprang. The same is true even of whistling. I recently heard a strange boy whistle as he went along the road in an entirely English part of the country, and, recognising the tone, addressed him in Irish, and found him an Irish speaker from Cill Gobnett, who knew English only imperfectly.

There is little doubt that Henebry could be controversial to the point of cantankerousness. The Handbook is idiosyncratic to the point of eccentricity, his theories sometimes obscurantist, and his description of the music in terms of a very personal notation hard to follow. Nevertheless there is no doubting his passionate engagement with traditional music, which came from long practice and observation. According to Francis O’Neill, he was ‘a fine freehand fiddler’, which I take to mean traditional rather than classically trained, and is reputed to have played several other instruments including a set of uilleann pipes made by himself. He was possibly the first person to make sound recordings of Irish traditional music in the field, concentrating on the songs and tunes of his native County Waterford. His collection of wax cylinder recordings is held by University College Cork, together with material donated to him by Francis O’Neill. Henebry is largely forgotten; he should be remembered.

The Reverend Richard Henebry or Risteárd de Hindeburg died at Portlaw on St Patrick’s Day, 1916. This brief sketch of his life was gleaned largely from the internet. As with all such research, one stumbles on serendipitous and fascinating pieces of information not directly related to the matter in hand. The next instalment of this column will be called ‘The Princes of Serendip’.

Published on 1 February 2010

Ciaran Carson (1948–2019) was a poet, prose writer, translator and flute-player. He was the author of Last Night’s Fun – A Book about Irish Traditional Music, The Pocket Guide to Traditional Irish Music, The Star Factory, and the poetry collections The Irish for No, Belfast Confetti and First Language: Poems. He was Professor of Poetry at Queen’s University Belfast. Between 2008 and 2010 Ciaran wrote a series of linked columns for the Journal of Music, beginning with 'The Bag of Spuds' and ending with 'The Raw Bar'.