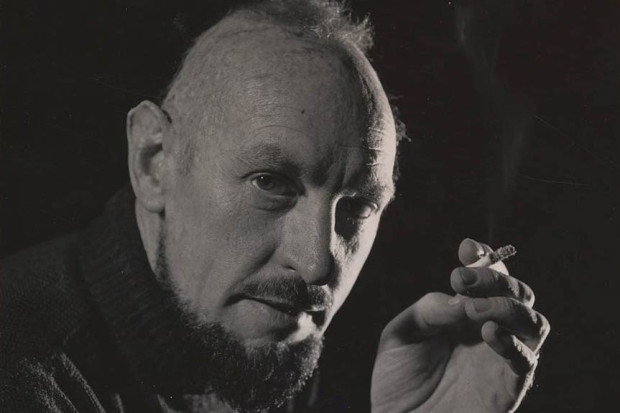

Composer Swan Hennessy (1866–1929) in the mid-1920s (Photo courtesy of the Hennessy family)

Celtic Connection or Talented Imitator?

No, I hadn’t heard of Swan Hennessy either. I don’t feel too remiss, though, for despite having had a modest reputation in his own life (1866–1929), he has since been almost entirely forgotten. Much of his work has never been performed, and that which has been, often not since his lifetime. Bird of Time, by Axel Klein (author of several publications on Irish music history, most notably O’Kelly: An Irish Musical Family in Nineteenth-Century France), is the first biography of Hennessy, and almost the first substantial discussion of him at all: the comprehensive literature review takes up all of five pages of this voluminous tome, and most of those few pages are dedicated to encyclopaedia entries. Hennessy’s discography is no more extensive: eight of his eighty-five-odd works have been recorded, six of them on a 2019 release by the ConTempo Quartet (Swan Hennessy: Complete String Quartets 1–4; Sérénade & String Trio, RTÉ Lyric FM label).

Despite his name, Hennessy was not really Irish. His father was a Corkman who emigrated to the USA when he was around sixteen, and his mother was an American – her maiden name was Swan, which is the source of Hennessy’s first name. (His baptismal name, Edward, was almost never used, even formally.) Hennessy spent his childhood in Chicago (where his father amassed a fortune large enough that Swan never had to work and was even able to support other artists); then he went to Europe at the age of around twelve. He probably spent a year in an Oxford public school, before going to a Stuttgart conservatory for around seven years (until c. 1886). So he was not really American either; indeed, he returned to the US as an adult only once and briefly. Following his time in Stuttgart, he seems to have moved to London, where he had his first marriage. This marriage was brief, and worth mentioning only because the wife, Lucy Roper, as a descendent on her father’s side of an Anglo-Irish landowning family, is one of Hennessy’s strongest connections to Ireland. Additionally, they had two children together, one of whom was born in Dublin; therefore, Hennessy almost certainly spent some time in the country at that point, though probably no more than a few months, and it is not clear what impact this sojourn had on his music.

Following the break-up of this marriage in roughly 1892, Hennessy seems to have disappeared until 1903. In these eleven years he wrote almost no music, and it is unclear what he did do, except that he probably spent it travelling Europe with his father, who had retired thence from the US (possibly for health reasons) around this time.

These fallow years (or whatever they were) came to an end when Hennessy father and son settled in Paris, most likely because Swan remarried, this time for life. So, at the age of thirty-six, this Irish-descended, US-born, English- and German-educated man adopted, though once again not fully, yet another nationality. And there he stayed (except for 1915–1919 when he lived in Switzerland, this time certainly for reasons connected to his father’s health). In Paris, Hennessy dedicated himself to composition, publishing some seventy works over the remainder of his life.

Such is Swan Hennessy’s non-musical biography. It’s rather thin, but then almost nothing survives that allows us to build a fuller picture. In his own hand, we have little more than some business correspondence in which personal details can be inferred, and some late op-ed-style publications in which he talked about musical issues of the day. From others’ perspectives, we have little more, with the only substantial piece being a 1929 interview by Lucien Chevallier. This is a shame: the passing mentions to him here and there suggest he was quite a character: a man of ‘legendary dynamism and humour’; a ‘numero… adored by his friends, and cordially hated by his enemies’; ‘as melancholy as a lacustrine landscape in Scotland, or as animated as the cheerfulness that tempered his northern nature’; ‘above all a humorist’.

Music

Musically, it seems Hennessy was always intent on being a composer, although he was also a competent pianist (he performed a lot of his own works). Towards the end of his Stuttgart studies, he started publishing music. The works of this period – Opp. 1 (1884) to 11 (1889) – are probably fairly considered juvenilia. They were for the most part not at all poor – indeed, the critics were often charmed by their warmth and melodiousness – but they were uncertain and conservative, firmly (though not entirely) in the shadow of their influences, in particular Robert Schumann. They were almost all for piano, and they were remarkably brief. Hennessy’s predilection for the miniature is in fact one of the most constant features of his oeuvre. (Klein writes that Hennessy ‘never quite shook off’ this characteristic, but this is not entirely right, to my mind, for I see no reason to think that Hennessy viewed his miniaturism as a weight to be shaken off: he seems to have been perfectly content working on this scale.)

Following his eleven-year hiatus, his Paris years can be roughly divided into two periods. Up till shortly before the outbreak of the First World War (Opp. 13–44), he wrote in the dominant Parisian ‘impressionist’ style: he wrote tonal music that was heavily indebted to Debussy’s harmonic innovations, and wrote strongly programmatic music: not unlike Debussy’s Préludes, but with more quotidian subjects (for example, his Op. 22 is a suite of piano pieces called In the Village). He was no firebrand, but neither was he behind the times.

At this point in his life, Hennessy was in a bit of a paradoxical situation. His works received fairly reliably positive (and occasionally gushing) reviews in the critical press, but these reviews were based almost entirely on the published scores. Actual performances were all but non-existent. One of the puzzles of Hennessy’s obscurity is this mismatch between critical reception, on the one hand, and performers’ and public interest, on the other. We will probably never have a certain answer here, but Klein’s hypothesis sounds plausible to me. It is simply that Hennessy was a retiring outsider in a city whose musical landscape was deeply tribal. Hennessy relied on his publishers to promote his music, which they did not do, and he had no networks of contacts to advocate for him either. He was not a member of any of the most prestigious Parisian musical societies and had not gone to a prestigious conservatory.

Celticism

Around 1912, the penny must have dropped for Hennessy, for he did join a musical society: the newly-formed Association of Breton Composers. This society was to connect art music with the traditional music of Brittany, where most of the composers hailed from (it is an irony that they were more welcoming of the foreigner Hennessy than the internationalist Parisian modernist circles were). Hennessy had already written a handful of works in an ‘Irish’ (or ‘Celtic’) style, the earliest in 1902 (Op. 12), and it is presumably by these works that he came to the Bretons’ attention, but this aspect of his style grew dominant from around 1912, and so we could call this ‘Celtic’ period his third period. It was also his final period; although the Association of Breton Composers was short-lived, its key figures remained in contact long after, and Hennessy remained in that artistic circle for the rest of his life.

Hennessy’s later music was not all explicitly Irish, or even Celtic more broadly. However, it seems that all his music from this time was infused with Celtic idioms. His music did not grow much more ambitious, whether in terms of the forces he wrote for, the length of his works, or his harmonic language. However, he does seem to have grown into his own skin very comfortably, and the reviews that Klein liberally quotes from speak again and again of his melodiousness, warmth, wit, and charm, as well as his command of counterpoint, instrumental balance, and form – though with a ‘but’ still constantly in the shadows about the slightness of his music. It is tempting to think of him as an arch-conservative, with his attachment to tonality and clear melody increasingly out of place; but though there is some truth in this (he was an outspoken and rather tedious critic of Schoenberg, and a critic called his Trois Pièces Celtique (1922, Op. withdrawn) fifty years out of date), we should not overlook the ways in which he was innovative: there were very few at that time who were bringing together traditional Celtic music and classical music.

From an Irish perspective, this is the most interesting aspect of Hennessy’s life. However, Hennessy’s ‘Irishness’ should not be overestimated. He imitated Irish idioms to the satisfaction of his French audiences, but then he was generally a talented imitator (he also wrote music in convincing Spanish and US idioms, and wrote several popular volumes of loving and sophisticated piano pastiches of popular composers, the À la manière… series (1923–27, no Op.)); and he was not sufficiently interested in Irish music to spend any time there, or to learn that the Scotch snap is not a feature (except in Donegal, but there is no reason to think Hennessy was aware of this). Klein floats the possibility that Hennessy’s adoption of an Irish persona may have been as much about making himself memorable in a crowded market as it was about any personal connection he felt to the country.

But then again, his connection should not be underestimated: Hennessy probably visited Cork in 1908 (as Klein argues on pp. 191–93), and dedicated his second string quartet (1920, Op. 49) to the memory of Terence MacSwiney, who had just died after hunger striking against British rule of Ireland (and whom Hennessy may have slightly known; Klein makes this case on pp. 193–94). Indeed, Hennessy’s second quartet seems to be the only contemporary Irish response to the independence movement (though the Englishman Arnold Bax also wrote some contemporary responses, most notably In Memoriam (1916)); those few Irish composers active at the time were Protestant Anglo-Irish, and so they were never likely to commemorate martyrs of independence. (Hennessy was a (probably non-practising) Roman Catholic.) So from a historical point of view if nothing else, this quartet is quite significant. (See pp. 268–9.)

The truth probably lies between these two. Another part of the picture may well be the simple explanation that Hennessy found himself part of a group of composers, performers and critics who appreciated, advocated for, and, in the 20s, performed his music. He naturally would have been inclined to continue writing in a voice that resonated with people. (This is an important element in deciding for ourselves whether our voice is genuine, after all.)

Weaknesses

It is hard to find fault with Bird of Time. To be sure, I would have liked more in some respects: an appendix of the chronology, more discussion of Swan’s place in music history more generally (especially in connection with his contemporary but far more advanced folklorist Bartók), more about Swan as a person. But these are minor criticisms, and I suspect unfair: I’m sure Klein could often simply not have done more given how little there is to work with. (For instance: how could Klein have connected Hennessy and Bartók if there simply is no connection between them beyond being folklorists? Klein’s general thoroughness inclines me to trust that if he makes no connection, there’s none to be made.)

The only substantial weakness of Bird of Time is not Klein’s fault at all. He says he is pleased that Schott, the publisher of so many of Hennessy’s works, agreed to publish his book, but the copy-editing, proofreading, and typesetting are all frankly dire. Typographical errors are not normally worth mentioning in a book review, but I doubt there’s a page in this text without errors – to say nothing of the ugly typeface. The musical examples, too, are riddled with errors: there are missing instrumentations or clefs, inaccurate bar numbers, poor-quality reproductions, etc. I suspect Klein did all this himself, and if so, he did the job as well as one would expect; but there is no substitute for professionals, and Schott are sorely remiss here, especially because of how simple it would have been to hire some. It is to Klein’s credit that he is such a clear writer that the book is still a pleasant read, and that the frequent grammatical errors almost never obscure Klein’s intended meaning. Still, though, he deserved better.

Legacy

I can’t say that Bird of Time left me with any strong desire to listen to Hennessy. If his contemporary critics are to be believed – and we have little else to go on – then though he wasn’t a poor composer, neither was he a genius. What would be the purpose of resurrecting him? Klein makes the case as best as one can, and I think he provides good reasons for returning to Hennessy. However, there are good reasons to do so much, and to do more than we have the resources for. I would prefer to see the limited and shrinking resources at the disposal of Irish performers spent on the living.

This disagreement is incidental, though. Klein is not primarily advocating for Hennessy, he is writing his biography. And this he does superbly. It is a heavy tome, to be sure, but as it may (even on Klein’s reckoning (p. 20)) be the last as well as the first biography of Hennessy, its comprehensiveness is entirely justified. This comprehensiveness is achieved through truly impressive archival research. Klein discusses almost every one of Hennessy’s works – published, unpublished, withdrawn, even lost – as well as giving as full a picture of Hennessy’s life as he can, and he does so through ample use of primary sources, including oral testimony of Hennessy’s grandchildren and fortuitous finds. It is no smaller achievement for this exhaustiveness to not just be exhausting to the reader.

If Klein is wrong about whether it is worth returning to Hennessy’s music, then what is the purpose of this biography? There are probably not that many people interested in Hennessy for his own sake, and despite living in the Paris of Ravel, Debussy, Joyce, and countless others, he never seems to have had more than fleeting contact with any of them, so his life is not likely to share any light on theirs. I think this book is nevertheless valuable. If Hennessy is not that interesting, the primary purpose of Bird of Time is to prove a negative: Did Hennessy meet these people and, if so, is he a missing link between any of them? Has he been so underrated that we’re overlooking a genius? The answers seem to be no and no. But these are answers worth having so long as the questions are worth asking, and Klein has supported the answers with such a wealth of evidence that the matter seems to be well settled. For this alone, Klein has done future historians of music a great service, and I would certainly recommend Irish and French university libraries acquire copies of the book.

Bird of Time: The Music of Swan Hennessy by Axel Klein is published by Schott. To purchase the book, visit https://en.schott-music.com/shop/bird-of-time-no441782.html.

Published on 13 May 2020

James Camien McGuiggan studied music in Maynooth University and has a PhD in the philosophy of art from the University of Southampton. He is currently an independent scholar.