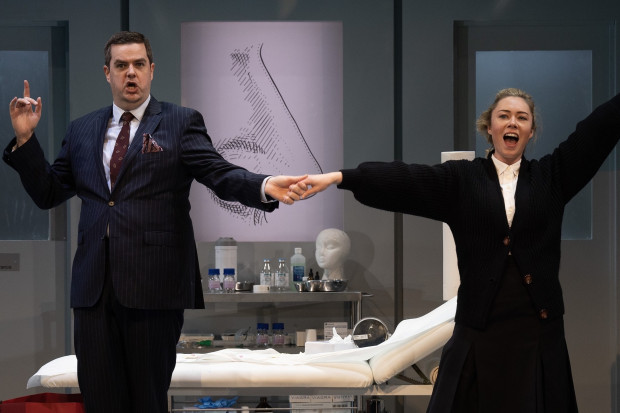

Visual artist Jesse Jones, Kevin Rafter (Chair, Arts Council), Orlaith McBride (Director, Arts Council), and actor Emmet Kirwan.

Can Anyone But Artists Themselves Solve Their Money Problems?

Last week, an article by the economist John FitzGerald appeared on the front page of the business supplement of the Irish Times. ‘Music really put us on the map with European citizens’, the title read. In the online version, an alternative title appeared: ‘Irish cultural exports helped pave the way for economic growth.’

Whatever the title, any Irish artist in 2020 could be forgiven for screaming at the page: ‘Yes… we know!’ It’s what musicians, actors and writers have been saying for years, and they don’t require an economic analysis to confirm it. Standing on stages across the globe they have seen the faces intrigued by Irish culture. After their concerts or shows, fans tell them about their love of Irish music and literature, about their connection to the country, about their personal story and how it is tied up with the island. Back home, they will meet different visitors who tell them too why they came, and how much Irish culture means to them. It doesn’t take much for any fiddle-player, actor or dancer to figure out that the economic impact of all these good vibes must be substantial, lucrative even.

FitzGerald tells the story of how, twenty years ago, after he gave a talk on the role that European Union membership played in Ireland’s economic growth, an Australian politician asked him about the role Irish music played. FitzGerald, who is a Research Affiliate with the ESRI (Economic and Social Research Institute), was taken aback because ‘music had not figured in any of my economic models’, but in the article he goes on to observe how Irish music has raised the profile of the country worldwide in his lifetime and helped attract EU citizens with specialist skills to migrate here. He concludes that this ‘asset’ that the Australian politician had mentioned ‘was not something that had been planned, or even required state funding. It just happened.’ (my italics)

I italicised the last line because last spring I spent weeks working on a radio essay for the twentieth anniversary of RTÉ Lyric FM in which I did my best to dispel the notion that music ‘just happens’ in Ireland, obviously in vain. For every example of talent we see on stage or in concert, we know the work that goes into developing it, and far from it not requiring state funding, music and arts communities have always used whatever fistful of cash has been going and multiplied it with their own time, energy and passion to make incredible things happen. FitzGerald’s article is well intentioned, but the idea that anything in music or the arts ‘just happened’ is like saying that the GAA or the Book of Kells ‘just happened’. It means the author does not realise the extent of work that takes place, and the artistic community has somehow not managed to communicate that.

The Irish Times article should also reveal to artists once again just how big the gap is between how they perceive the world around them and the view of the political and economic influencers. Everyone in the arts has been talking about the economic impact of what they do for at least two decades and it has barely registered. It is time for a different approach.

Call it whatever you want

Two weeks ago, the Arts Council published a Paying the Artist policy, which is a very welcome initiative because it keeps the issue of artist funding and income on the table – indeed, FitzGerald’s article seems to have been sparked by its publication. The policy makes it clear that the ‘underpaid or unpaid contributions of artists represent a hidden subsidy to the cultural life of Ireland… this is unfair and unsustainable.’ Unfortunately, however, it is not within the power of the Council to ensure better conditions because the Council’s own funding, upon which arts organisations are reliant, has been run ragged by politicians. Every political party that has been in power has cut it, and then slowly rolled back parts of the cuts under pressure.

So what can artists do? And why have their arguments about the economic value of the arts not worked when it seems they work for every other sector? I think it is because we as an arts community work in the domain of the word and the imagination, and we presume that a passionate truth well told is all we need to get our point across. The reality is different. Financial decision-makers make moves based on degrees of resistance. They pay what they have to, and what they cannot avoid paying for, but right now plenty of music and art still seems to ‘just happen’ no matter how little they invest in it because it is subsidised by the artist.

The only way for artists to change their circumstances, therefore, and send a message right back up to Government and every company and organisation that employs them, is if they come together and agree on minimum standards of payment across the board, and then do not budge from them. Call it unionisation, call it an artists’ agreement, call it whatever you want, but it is now essential. Nothing else is going to change their fortunes – not Arts Council policy, not a political party, not another international award.

Previous generations might have been cautious about such collective action. They would worry that they would end up with less work, but the edifice of Irish arts and culture is much bigger now, and it is entirely reliant on the artists at the bottom subsidising it. If today’s artists truly believe in the value of what they do, if they really believe that their work makes a difference, then they have to start asserting themselves, unapologetically, in financial-based action. This generation has the confidence to do this. I could see it in the way the new generations spoke at the Trad Talk music conference last November; and it’s there in the work of Theatre Forum and the National Campaign for the Arts. The time for waiting is over.

Published on 26 February 2020

Toner Quinn is Editor of the Journal of Music. His new book, What Ireland Can Teach the World About Music, is available here. Toner will be giving a lecture exploring some of the ideas in the book on Saturday 11 May 2024 at 3pm at Farmleigh House in Dublin. For booking, visit https://bit.ly/3x2yCL8.