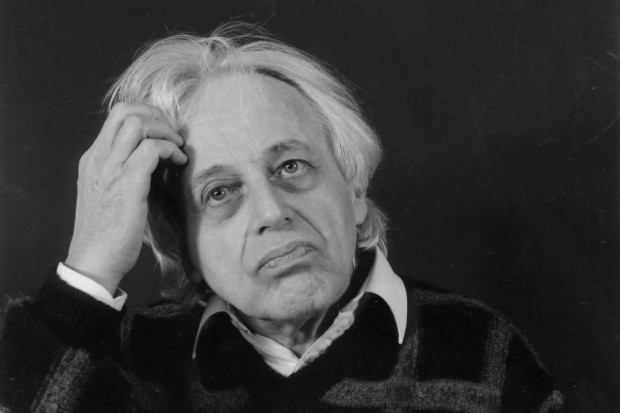

Pierre Boulez

Boulez is Alive

Pierre Boulez, the composer, conductor and music advocate, was 90 in March. He is the last man standing from a post-war generation of innovators that included Stockhausen, Berio, Ligeti, Xenakis, Carter, Babbitt, Feldman and Cage. His major works, such as Le marteau sans maître, Pli selon pli, Répons and Sur incises, were very influential to a following generation of composers, who are now no longer young. These works are now canonical, turning up sporadically at major festivals, but thanks to the passing of time, the plurality of contemporary music, and the endless seeking after recent work, they are not at all as well known today.

A large majority of musicians, composers and commentators, I would hazard – judging from the general trend of public discourse on music – have not really engaged with his work. While the general music public might regard him as canonical, and therefore at least on a list for consideration, specialists are more likely to bypass him for having lost relevance. To them he reflects an old-fashioned world of theoretically informed and historically connected musical practice. There is no doubt that the level of complexity of his scores, and the extensive material on how they were produced, is off-putting to generations who feel that they should have all kinds of other knowledge under their belt; a list that includes perhaps Feldman, Ligeti and Cage but also the so-called minimalists, and then a panoply of much more recent practice from all the younger living composers, whether experimental, post-modern, post-minimal, spectral, ambient and so forth. Perhaps there just isn’t time!

The important thing about Boulez as a composer is the body of work, widely accessible through recordings. It speaks for itself. That is why his birthday has been noted widely this year, albeit not by the major orchestras here in Ireland, but from the Met in New York to the Aldeburgh Festival to the BBC Proms. And yet, at the same time, the image of Boulez is negatively coloured by superficial knowledge of a number of things: his mode of working (revisiting, re-writing and extending works over many years to the point where commentators want to accuse him of being unable to finish), his often abstruse writing on compositional technique, his polemical writing and statements on other music, and his dominance of the French musical scene.

The music and the writing do frequently share the attributes of constant revision and re-packaging. For someone who started out studying maths, and seems to offer absolute and abstract methodology, this seems worrying on the surface, but certainly in the music (less so in the writing!), the re-visits have been entirely forgivable as they have usually led to greater works than the work being revised or even cannabilised. It leads to another important trait when we try understand Boulez’ whole output: the role of intuition and free invention. Although he presents an image of music as supported by cool reason and rational progress, he is not, in his work, entirely suppressing poetic fancy. A close analysis (by no means easy) of how a work such as Le marteau was actually written reveals material being created in profusion and then trimmed according to what Haydn described as the unteachable: taste.

Total innovators

Boulez was one of the major voices in the European modernist group – Nono, Stockhausen, Berio and Maderna among others – associated with the summer courses held at Darmstadt from the early 1950s to 60s. They created an uncompromising and theoretically complex style of music that was to define avant-garde practice for over a decade. Boulez was one of the few who worked for a short while using ‘total serialism’: an extension of Webern’s earlier rather abstract and condensed version of serial writing. Total serialism extended this pitch ordering concept into duration (hence rhythm), dynamics, and even timbre, creating a very fractured and abstract musical surface. Indeed, he is one of a small group who can claim to having invented this procedure.

This technique grew out of a scientific mode of thinking about the basic elements, or parameters, of music (time, pitch, amplitude, envelope, and so on) that were seen as ‘atomic’ in the sense of irreducible, generic, essential. Although strict use of this technique quickly became of less importance to Boulez – he was keen to move away from the rather static qualities it had engendered in the early masterpiece Le marteau – the parametric and serial way of thinking underpins a great deal of what is heard as modernist music, lending structure and order where many traditional and reassuring musical features are being avoided.

Writing on his own compositional techniques, the most important English language sources being Boulez on Music Today and Orientations: Collected Writings, Boulez worked through things in an orderly way, reflecting his mathematical training (he studied maths for a while before turning to music). He was a composer who, like Varèse, Stockhausen and Xenakis, felt that new music should reflect new knowledge in maths and physics. In other words, the ideas around musical unity and form that had underpinned older classical music were now part of an outmoded philosophical and scientific world, and would have to move forward and take account of the newer and more complex understanding of reality, informed by areas such as statistics or information theory. His writing uses terms such as ‘density’ rather than ‘number of notes’, and he was keen to work out (or at least posit) hierarchies and guiding schemata. For example, the relationship of small-scale musical material to the greater musical layout of a piece was to be revolutionised to achieve greater integration, so that similar procedures could give rise to structures on all levels. Thus he and the other composers associated with Darmstadt were really changing the understanding of how serial thinking should impact on the total form of music, rather than solely on the choices of pitch.

Boulez’ writings are very clear on taking into account what the listener will deduce from complex sound phenomena, and how that should feed into musical structure. The extent to which he was concerned with this remains under-appreciated. The impression most musicians would have is that he demanded far too much of the performer and the listener, yet he was concerned with this in a very realistic way, for example setting certain limits: never using microtones, citing them to be unreliable in the hands of current performers, and avoiding glissandi, insisting they were banal. He did believe that challenging performers would lead to generally improved levels of technical facility, and this has been proved right over the years. Ironically, he has trouble with posterity on two opposing fronts: for that slight conservatism arising from his practical work with musicians, and for the avant-gardism of his work.

These technical writings are opaque and little read. As with other composers writing on technical things, he found it more expedient to use examples from his own compositions, but to emphasise the universality of the issues, he generally left out the references to specific passages and works, leaving the examples to speak in the abstract and without easily traced sound examples. This was in keeping with his scientific outlook – trying to establish useful norms – but it came across as rather egocentric. It was also in keeping with his practice of preferring to look at scores rather than listen to recordings: as a conductor, it is known that he had phenomenal aural skills, and his preference for the score is to do with unearthing the intentions of composers that the usual available recordings failed to grasp and realise.

They don’t exist

He is known also as a polemicist, with many short incendiary essays on Schoenberg, Beethoven and Wagner among others (also found in Orientations); indeed these writings have been described as modelled on the rhetoric of the communist journalism of the day! His polemical articles certainly have a flavour of the Marxist concept of unleashing newness out of destruction or denigration of the old. His most famous essay title is ‘Schoenberg is Dead’, written only shortly after Schoenberg’s death in 1951.

Regarding his critiques of other composers, these are always revealing. His bold conceptions of the useful versus useless composer remains tied up in the ideal of ‘being interesting’, which amounts to innovation of technique. He dismisses composers who are too lazy to create a new musical language for themselves, and instead use those that other, better composers, created for themselves in the past. He does not dismiss a composer’s whole output, rather he points out what to him are the good and bad points and works.

‘They are wasting their time,’ he said about neo-tonality in French music of the 2000s. ‘There are always people who will take an easy intellectual path. Poulenc coming after Sacre [Stravinsky]. It was not progress. I cannot polemicise with these people – they don’t exist, simply that.’

He seems to go very far – too far – in rejecting radical musical agendas that play with tonality in genuinely fresh ways, or that explore parameters in way that Boulez finds too dangerous. Whether it is Finnissy, Sciarrino or Lachenmann, there are many things to do with collapsing expectation, working along a spectrum from noise to atonality to tonality, playing with mixed contexts, all of which he would dismiss as ‘not interesting’. But at least he is speaking consistently from a position of earned authority.

I would say to all those active in music: don’t dismiss Boulez. I would not agree with all of his views, but he is consistent on pursuing questions of quality – and his music above all shows consistency: in the pursuit of high-quality compositional technique, and by evolving in time, in light of rigorous self-criticism. While it is already widely deemed almost irrelevant in the light of current fashions, his music will most likely stand out as a beacon when objectively assessed in the far future. As an example of how an artist should live, he should not be wished away, which is what seems to have already happened.

Published on 29 June 2015

John McLachlan is a composer and member of Aosdána. www.johnmclachlan.org