Gerhard Markson conducting the RTÉ NSO with pianist Finghin Collins

Love and Conflict at the NCH

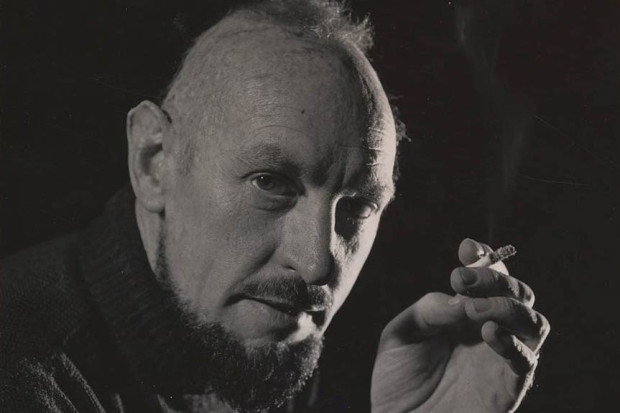

Last Friday night’s concert at the National Concert Hall marked the 70th anniversary of the RTÉ National Symphony Orchestra. Originally founded in 1948 as the Radio Éireann Symphony Orchestra, this celebratory concert brought together some of Ireland’s finest talent in the form of pianist Finghin Collins and soprano Orla Boylan, both of whom have enjoyed a long association with the orchestra. While the post of principal conductor is currently vacant, it was good to see the return of the former principal Gerhard Markson, whose reign from 2001 to 2009 is starting to look like something of a golden period when set against the backdrop of the NSO’s current woes.

The antithesis of the showboating conductor, Markson’s understated style belies a precision and meticulous concern for musical shaping that was very much in evidence in the first substantial piece of the evening, the Prelude to Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde, whose contours were nicely judged dynamically with just enough restraint exercised at the conclusion to leave room for the celebrated resolution in the ‘Liebestod’. The latter received an assured performance from soprano Orla Boylan even if some of the lower notes in the lead up to the climax didn’t quite project over the orchestra.

Filigree detail

Belfast born composer Deirdre Gribbin’s piano concerto The Binding of the Years was originally commissioned and premiered back in 2012 with Finghin Collins as soloist. For this occasion, she composed an extended slow movement to go in between the two existing ones bringing the concerto into line with the traditional three-movement concertante format.

Gribbin’s music tends to focus on shifting soundscapes that merge seamlessly into each other and her style of orchestration is very much aimed at providing a variety of shimmering surfaces, hence the requirement of a substantial percussion section. Although there’s no doubting her considerable skill as an orchestrator, the fluid melting of one glistening texture into another resulted in a certain sameness after a while and the absence of any real dissonance gave the music a kind of monochrome whiteness. The filigree detail is all done in the higher registers with the lower instruments resigned to holding long sustained notes for extended periods at a time. The writing for the piano part in both of the outer movements seemed particularly undifferentiated consisting almost entirely of either swirling repeated figures, trills or two-handed tremolandi.

There was a brief respite from this in the third movement where the piano texture shifted to syncopated chords and there emerged some genuine dialogue with the orchestra, but it wasn’t long before the swirling figures reappeared with an almost Gretchen-like predictability to bring the concerto to a close. The newly composed second slow movement had more variety and was possibly the strongest of the three but none of the movements really tested the virtuosity of Collins who otherwise gave a solid performance.

Intense and impassioned

The second half of the concert was devoted to a selection of movements from Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet. Due to their stop-start nature, such selections from ballets, however glorious, often lack the kind of cumulative punch to the second half of a concert that a well-performed symphony can deliver. Nevertheless, the NSO managed to reserve their most intense playing for two of the later numbers with some impassioned contributions from the strings and brass during ‘Romeo at the Grave of Juliet’ while the ‘The Death of Juliet’ at the conclusion was tenderly managed. The famous ‘Dance of the Knights’ was performed with the required muscularity and the orchestra exhibited considerable dexterity in the faster numbers with the tight interplay between the orchestral sections in the ‘Death of Tybalt’ being particularly impressive.

Conflicted

Despite the excellent performances, the presence of an Irish premiere on the programme and the rare instance of a packed NCH, it was nevertheless hard to come away from the concert without feeling somewhat conflicted. The theme of love that united both of the big items on the programme can hardly be said to characterise RTÉ’s relationship with its flagship orchestra at the moment. With its future the subject of an upcoming review that many fear is simply a way for RTÉ to seek justification for further cuts to the orchestra’s already depleted ranks, cynical murmurings could be overheard at the interval suggesting that a programme of Haydn’s ‘Farewell’ symphony paired with Shostakovich’s ‘Leningrad’ might have made more sense.

With all this in the back of one’s mind, Brian Byrne’s opening fanfare Seachtó – an ecstatically bombastic opening fanfare that wouldn’t have been out of place at the opening ceremony of the Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang – sounded particularly hollow. Also it was quite obvious that a large proportion of the full-house crowd that miraculously materialised to share in this auspicious occasion consisted of invited fair-weather guests rather than regular punters as evinced by the unrestrained clapping that kept breaking out between movements, despite Markson’s attempts to keep the intervals between successive movements to a minimum in order to discourage such unruly breaches of etiquette.

But in the end, the night really belonged to the players, some of whom were clearly emotional by the evening’s conclusion. Hopefully the necessary arrangements can be put in place by our art administrators to ensure that the orchestra celebrates its 75th anniversary in a few years time safe in the knowledge that a brighter future lies ahead.

For upcoming concerts, visit https://orchestras.rte.ie/

Orla Boylan

Published on 21 February 2018

Adrian Smith is Lecturer in Musicology at TU Dublin Conservatoire.