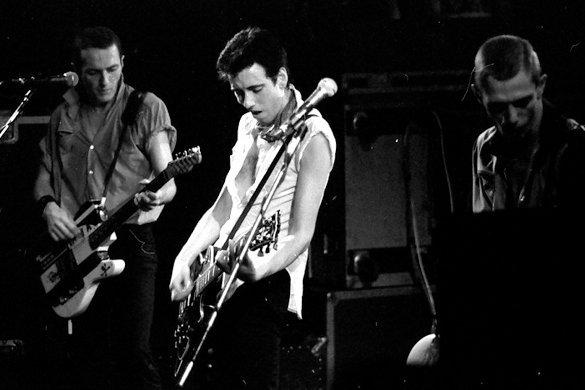

The Clash performing in Norway in 1980. Photograph: Helge Øverås.

I Wanna Riot of My Own

White Riot: Punk Rock and the Politics of Race

Stephen Duncombe and Maxwell Tremblay (eds.)

Verso, 2011

The usual approach to Punk and its sibling radical subcultures is by way of intergenerational tensions, reasserting the belief that today’s revolutionary will always become tomorrow’s reactionary. This is the main thrust of Daniel S. Traner’s seminal 2001 Punk studies article, ‘L.A.’s “White Majority”: Punk and the Contradiction of Self-Marginalization’, which finds a pivotal place in Verso’s new reader, White Riot: Punk Rock and the Politics of Race.

In his article, Traber accepts Punk’s ability to establish a ‘permanent alternative to the corporate apparatus of the music industry,’ but he also knows that, as historical movement, Punk was doomed to failure in its ‘subversive promise’ of sudden arrival at a new world. Punk’s thoroughly white-bourgeois origins, Traner argues, would mean that any attempt at ‘tapping into the aura of the Other’ would always meet its own image at the other end of the circle of poverty fetishism, personal expression, sovereignty of the individual, classical liberalism: ‘Punk’s discourse finally becomes an extension of the parent culture’s belief system; an unconscious affirmation of the materialism and political self-interest this “counter culture” claims to oppose.’

In the same way, and despite its revolutionary zeal (it calls, no less, for the destruction of America as it stands), Joel Olsen’s 1992 ‘A New Punk Manifesto’ can’t really find anything in Punk’s achievements to that date beyond consolation: ‘Out of the waste heap of middle-class values and shopping-mall esthetics, we’ve built a [Punk] culture that has allowed us to survive the post-industrial world while at the same time salvaging some semblance of our independence, freedom, creativity, and human integrity.’

These essays and ideas remain valid, but the strength of White Riot is the way in which it submerges commonplace assumptions with a much broader and altogether more problematic aesthetic, one that extends from the hipsterism of Norman Mailer’s 1957 essay ‘The White Negro’ to the type of Nazi apologia (and Hitler-love/fetishism) that the British band Screwdriver peddled in the 1980s. Patti Smith (pictured) may have established the borderline in her 1978 ‘Rock ‘n’ Roll Nigger’ (‘any man who extends beyond the classic form is a nigger — one sans fear and despair — one who rises like rimbaud beating hard gold rhthymn outta soft solid shit-tongue light…’), but punk rockers would soon come to find that positioning themselves along the divide was fraught with danger.

The Punk Moment

And so the book flits its gaze between the strong and the confused: on the one hand, those of the ‘White Minority’ and the ‘Punky Reggae Party’ mindsets, ready to challenge the idea of white supremacy and orthodox hegemony, and to reach across the divide in solidarity; and on the other hand, the ‘White Power’ armies who could only define themselves through binary thought. 1980 becomes year zero, a portentous date, with its piling of voids and circles, and so opposed to the prophesies of the Clash’s ‘White Riot,’ or of Culture’s ‘When the Two Sevens Clash,’ which saw 1977 as the moment of Rastafarian destruction, revelation and delivery. Here, Punk history gives way to the Punk moment — the nihilistic and animal urge to act… without conscious motivation, and whatever the consequences. 1980 sees Thatcher in Downing Street and Reagan on the campaign trail heading for the White House to reinstate the myth of white universality and to inaugurate the three decades (and counting) of neo-liberal economics, or, as the old Marxist writer John Berger likes to call it, ‘economic fascism’ — could this, in itself, be an obscene negative projection and magnification of the punk moment?

And so the wanton, greedy decade welcomes the Oi! brigade in Punk — lost, straightforwardly racist and thuggish ‘boneheads’ — but also the outpouring of a certain radical assumption of ‘otherness’ into cities and ethnicities around the world, all based, suddenly, on the complexities of individualism.

This view of a subculture’s history doesn’t mean, however, that White Riot bypasses Punk’s ragged obstinacy: ‘What is it about punk rock,’ the book’s editors Stephen Duncombe and Maxwell Tremblay ask continually, ‘that produces, at one and the same time this (a) acknowledgement and rejection of privileged whiteness, (b) desire to join in solidarity with other races struggling for change, and finally (c) a difficulty in producing anything concrete or lasting from those desires?’ The inability of most of the contributors to attain any real perspective on these issues (due, no doubt, and understandably, to their proximity to the action) leads White Riot eventually and inevitably over its nearly 400 pages into a frustrating series of self-defeating tautologies; but it’s also the case that the promise of an aesthetic release hangs tantalisingly over these pages.

Beyond the Intellect

If Punk needs to be, as White Riot’s editors claim, ‘gloriously uncivilized’, treasonous, guilt-ridden, outrageous, courageous, psychopathic, camp, anarchistic, and all of these, ideally, in one and the same moment, then a unity of purpose (a politics) is going to be impossible to find. Punk cannot engage with ideology, because, arguably, it works on an altogether more radical, existential level. Punk wants to speak poverty through poverty, and at the same time to antagonise, provoke, (and even to enjoy, perversely) the enemy’s way of life, of over-expenditure, over-production and over-consumption — so it draws in poverty through its musical materials, and excess through its attitude. Punk also needs to speak beyond the intellect, and as it does so it draws out the Punk moment that surely powered so many mavericks of artistic expression.

The one overriding urge that links these radicals is the need to fight against the idea of ‘the project’, of sacrificing the demands of the present moment for a future benefit. Was George Bataille, for example, proto-Punk when he talked about the ‘evil of writing’ and said that he ‘rejected discourse’ and celebrated only ‘non-knowledge’? Or when he said this: ‘What I teach… is a drunkenness, not a philosophy: I am not a philosopher, but a saint, perhaps a madman.’ And then there’s the animality provoked by ‘exposure to a traumatic dimension of political power where a creaturely cringe is called into being, excited by… the peculiar “creativity” associated with the threshold of law and nonlaw’ — these words are from Eric L. Santner in his recent study of uncanny impulses in literature: On Creaturely Life.

And so the idea of the ‘Punk moment’ becomes a much more useful way to approach this subject of a movement that doesn’t move, of a form of expression that pursues ‘the erosion of meaning itself’ — this bundle of paradoxes and contradictions we call Punk. Throughout the post-war years punk rockers became agents provocateurs in all of the major political struggles in Britain and the United States, but they did so with wild abandon and complete irresponsibility, free from the trappings of considered thought and, indeed, of logic itself. This meant that bands like Sham 69 could align themselves politically with the socialist Rock Against Racism, but socially with the political National Front. The image conjured by Steven Lee Beeber in his ‘Hotsy-Totsy Nazi Schatzes: Nazi Imagery and the Final Solution to the Final Solution’ of Debbie Harry making love with Chris Stein, ‘a Nazi flag beneath them, its red backdrop in perfect counterpoint to her blonde hair’ says it all — simultaneously crude and ironic, rousing and deflating. Pictured: Stein and Harry with Andy Warhol.

Punk and Nothingness

There is, after all, a lot of joy and humour in Punk, or perhaps we should say a (horny) kind of jouissance. Even the word, with its grandiloquent capitalisation, is a provocation; origins unclear, it loiters on the margins of the commonly understood. The Oxford English Dictionary provides a multi-layered prehistory of meanings from the eighteenth-century word for prostitute, or, more precisely, strumpet, harlot (and its gender equivalent, the compliant young male homosexual), or of rotten materials used combustively in a bone-dry state, or of something worthless that nonetheless makes its point with a flourish (‘phosphorescent punk and nothingness’ from the nineteenth century).

But following the trail of implications through the sometimes direct and sometimes accidental associations in these dictionary entries reveals notions of acuity and timeliness: a pungent, puncturing punctus — a point, a punctuation mark, a cadence, an endpoint, or even, as in the case of punctograph, ‘an instrument for the precise positioning of foreign bodies imbedded in bodily tissue.’ This last association remains in the mind throughout a reading of White Riot. Whatever commentators throw at Punk, in accusation or vindication, from left or right, or from the populous middle ground, it will resist and remain, determinedly, pointedly, an instrument — a means of pricking the infected parts of the body politic to reveal exactly what festers beneath the skin.

Published on 17 October 2011

Peter Rosser (1970–2014) was a composer, writer and music lecturer. He was born in London and moved to Belfast in 1990, where he studied composition at the University of Ulster and was awarded a DPhil in 1997. His music has been performed at the Spitalfields Festival in London, the Belfast Festival at Queen’s and by the Crash Ensemble in Dublin. In 2011 the Arts Council acknowledged his contribution to the arts in Northern Ireland through a Major Individual Artist Award. He used this award to write his Second String Quartet, which was premiered in 2012 by the JACK Quartet at the opening concert at Belfast's new Metropolitan Arts Centre (The MAC). Peter Rosser also wrote extensively on a wide range of music genres, with essays published in The Journal of Music, The Wire, Perspectives of New Music and the Crescent Journal. He died following an illness on 24 November 2014, aged 44.