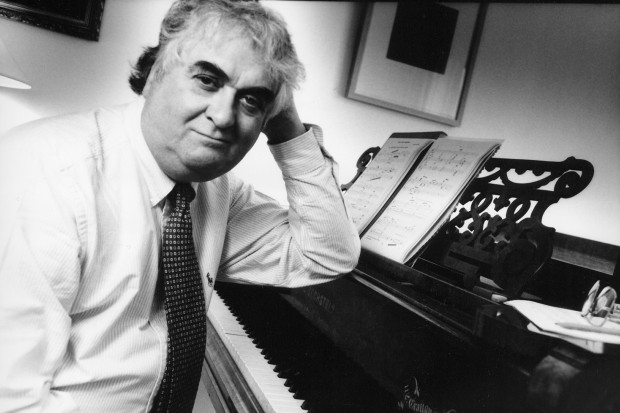

John McLachlan

Avoiding Convention

John McLachlan has been a notable presence on the contemporary music scene for many years, not just as composer but also as commentator and, for fourteen years, as executive director of the Association of Irish Composers. So it comes as something of a surprise that this is the first CD devoted entirely to his work. First, a compilation of live performances of works composed between 2007 and 2017 comes with a sort of warning for the listener in the form of a programme note for the electro-acoustic work Sparśa (2015). It states ‘when you hear a new challenging piece of music the brain scrambles to tell you it is like such-and-such. In the ideal situation we might strive to let the sounds themselves come to us for as long as possible hearing them for what they are and not for what they are like.’ In some ways, this task is made easier by the fact that his music is not quite like most other Irish composers’ work (though comparisons still act as a useful shorthand for evoking particular qualities of the music). He has never aligned himself with any of the prevailing compositional fashions, and whereas most composers seem to feel now that the only path to becoming a composer is a self-reflective composition PhD, McLachlan decided that a rigorous musicological doctoral study of the work of Boulez, Carter, Lutosławski and Xenakis would be of more benefit to his development.

In an interview with Ben Dwyer in 2013, McLachlan noted his ‘lifelong habit of avoiding repetition and overtly motivic development’, his methods of macro-organisation of material, and the problems he had with the unconvincing use of melody within quasi-modernist pieces. By contrast, his notes to the new CD highlight a shift in works from 2013 towards a more relaxed approach ‘in the direction of thematic writing or at least free melody’. In more general terms McLachlan has stated that he did not have a single compositional language but rather a number of ‘idiolects’ or techniques ‘that create the characteristic colours and moods of the music’ and highlighted his preference for continuity created from asymmetrical material. Certainly the works on this CD display the tendency to avoid any sort of traditional narrative form, and conventional endings are generally avoided. While McLachlan is not an uncritical admirer of heroic modernism, he is dismissive of more reactionary trends within postmodernism or the desire to aspire to the therapeutic or the status of wallpaper. It is therefore no surprise that the music on this CD resists easy assimilation.

Worthy of revival

Of the six pieces on the CD, Incunabula (2007) is probably the most immediately appealing. It consists of four blocks of ideas. The first with its stabbing chords and rising figures links neatly to the second in which trenchant chords predominate all parts of the orchestral texture while the rising figures disappear. The third is a somewhat Feldmanesque exploration of delicately scored textures while the final section unexpectedly opens out into a far more lyrical space, unperturbed by persistent brass chords. As tends to be the case with recordings directed by Gavin Maloney, the performance is fairly blunt and lacking in interpretive refinement. Of course, one has to qualify this by noting that this recording stems from a live lunchtime concert performance put together with a minimum of rehearsal. However, the performance suggests this is a work worthy of revival and makes one curious about the other orchestral works (Octala, Taca and Arcana) that form a four-part cycle with Incunabula.

Golden Circle (2010) and Diomedea (2017) are both formed from a long opening section followed by a brief highly contrasting section. This is a somewhat curious gambit, in which the second section runs the risk of sounding like an underdeveloped second movement rather than an integral if contrasting section of a one-movement structure. Diomedea is scored for the unusual combination of saxophone and recorder, played with great flair and rhythmic energy by Laurent Estoppey and Anne Gillot respectively. The bulk of the movement features contrabass recorder, which kicks off a rather appealing riff against which the saxophone reacts with more melodic material. This launches much imitative dialogue between the two instruments, enhanced by the deft exploitation of the radically different timbres of the instruments and the reverberant acoustic of the church in Bern in which it was performed. In this case, I wasn’t quite as convinced by the sudden jump two minutes from the end of the piece to a treble recorder and some rather more conventional sounding material, but overall the work has an entertaining strangeness.

In the first part of Golden Circle the Sond’Ar-te Electric Ensemble, tautly directed by Laurent Cuniot, is divided into two groups – piccolo, violin and the treble register of the piano in one and cello, clarinet and lower piano register in the other – creating a somewhat 1950s-ish fragmented texture, though the melody has interesting micro-tonal inflections often created via gradual glissandi. These lines are augmented by a discreet electronic component. After about seven minutes of this material, there is a pause followed by a different texture in which all the instruments have individual rising and falling lines moving at different speeds. The CD liner note states that the work ends ‘with ironic intent, in a loop’, though I’d imagine this would not strike any listener without the aid of the programme note. In this case, the structure came across as strongly coherent, the two sections complimenting each other and giving the piece a satisfying shape.

Sparśa (2015), the longest work on the CD, is an electronic work based on sound samples from the drummer Gary Raymond. The programme note explains the title as referring to the moment of perception when a brain registers something before it begins to interpret it ‘with notions of taste.’ Despite my best efforts, I found my notions of taste were unwilling to switch off and indicated strongly to my brain that the work rather outlasted its welcome, if one was to listen in an engaged rather than disengaged fashion. The sounds extracted from the samples were frequently interesting or appealing and individual moments in the work were very striking but the rather flat, directionless nature of the material made it hard to sustain interest in the piece

Collage techniques are used to structure both Aurora (2013) and Dog Ear (2013) though to rather different expressive effect. At first one might be forgiven for suspecting some sort of ironic intent in Aurora, as the piece seemed to cram together a load of ‘new music’ clichés: some brushing of the piano strings, glissandi, a cluster chord, a few harmonics, a passage that jumps up and down between the highest and lowest ranges of the piano, the appearance of the inevitable bass clarinet, some harmonic glissandi and so on. However, it continues to shuffle around these ideas with a sort of grim determination and the singlemindedness of the approach manages to make the material more absorbing as the work progresses. Less convincing was the sudden appearance of some electronically processed birdsong as the work concluded (with the lower pitched material sounding not unlike the contrabass recorder in Diomedea). It almost seemed like an attempt to disguise the more traditional conclusion of the instrumental music, but it is possible this works rather better as a sort of theatrical coup in a live performance.

Playing with text

After an hour of music that frequently seems to go out of its way to evade direct emotional expression, Dog Ear comes as something of a surprise at the end of the disc. The piece consists of samples of the composer’s mother, the poet Leland Bardwell, reciting her work. Some of the recordings were made of Bardwell reciting her work from memory aged 91 and the strongly characterful rasp of her voice, oozing experience, acts as a strong anchor for the piece. Against this are placed a variety of ‘concrete’ sounds such as a typewriter, pages rustling, whispered text, and samples from McLachlan’s compositions. McLachlan plays around with Bardwell’s text and our perception of meaning; sometimes short startling phrases are heard in isolation only later to be placed in the context of longer lines of poetry. Other phrases maintain their mystery, just as the ‘ordinary’ nature of many of the concrete sounds gives the sense of a personal landscape that is simultaneously familiar and enigmatic. With its directness heightened by the overall context, the work forms a powerful conclusion to the CD.

The CD is clearly designed to give as broad a range of pieces as possible, and one finds oneself wondering if this is why it is hard to isolate elements across the disc that would make up a distinctively personal language, or whether, as McLachlan suggests, the individual element is to be found in the processes followed rather than the language itself. Despite reservations about certain aspects of the disc, it forms a persuasive calling card for a composer with a strong technique capable of sculpting a compelling argument from his chosen material, even if by times the material seems rather unpromising. However, it has to be stressed that this is music that requires quite a lot of listening before it can be grasped and it is sometimes only after repeated listening that one can appreciate a piece that seemed uninviting on first listen. This of course highlights the importance of CDs like First for Irish composers, as so often in the scramble for an endless stream of premieres works do not get the repeat performances that would enable audiences grapple with complex pieces like these. The performances of the instrumental works on the disc all sound highly committed and while there is the odd bit of coughing and spluttering from Irish audiences, those in Switzerland and Portugal are commendably quiet. The production by Farpoint is excellent and the physical CD version comes in an attractively designed package with programme notes by McLachlan.

First by John McLachlan is available to purchase from Farpoint Recordings. Visit www.farpointrecordings.com.

Click on the image below to listen.

Published on 17 June 2021

Mark Fitzgerald is a Senior Lecturer at TU Dublin Conservatoire.