What I Meant to Say Is...

At last year’s opening lecture of the BBC’s Free Thinking Festival, novelist and essayist Will Self, no doubt expecting to deliver a routine embrittlement of middle class conformism, found himself in cosy consort with his most eloquent challenger from the floor. Self’s lecture – ‘Naturalism and Sanity: is the mind really as it’s portrayed?’ – looked at the easy fictions propounded by the novel and its representation of consciousness. He argued that ‘the minds of some of our most beloved and believed-in fictional characters have as great a resemblance to the reality of the psyche as stick figures do to human anatomy’. He went on to say that the illusion of sense and logicality in the fictional thought process is not necessarily a lack but part of a ‘process of collective, although unconscious therapy, whereby writers and readers alike are engaged in persuading one another that they also have minds just as legible and therefore comprehensible’. During the subsequent question-and-answer session the audience member said, more or less, yes, but so what? Isn’t this easy fiction, this suspension of disbelief within readily accepted formal conventions what we actually like about art? Don’t we just love lying to ourselves? It persuades us that we are all the same and in that way it saves our sanity. Isn’t it true, moreover, that art is impossible without this delusion? Seeing his interlocutor invade his radical terrain so easily and with one simple reactionary step, Self was forced to concede that he wasn’t trying to lead a revolution; after all, he said, ‘it would be the first revolution led by a man in a tweed suit!’ Bourgeois sensibilities very quickly reasserted themselves.

Self had stumbled into one of the most problematic areas of art – that of metaphor. Do we really say what we mean and do we mean what we say? Derived from the Greek phoria (to transfer), metaphor is the slipperiest of concepts. Originally part of Aristotelian rhetoric it was the thinking person’s greatest ally (it made language come alive with Mercurial flight) and her greatest foe (it transgressed the rules of taxonomy). In more recent times, and especially within the avant-garde of early twentieth century Europe, the subject found itself further politicised and the very word stood aligned with the most reactionary forces; the sequence of image-action-body-politics-proletariat-justice, according to the philosopher Peter Osborne, is seen to stand opposed to metaphor-contemplation-intellect-morality-bourgeoisie-oppression.

Metaphor is obviously a powerful force and one that is subject to strict control, even in the most liberal of societies. It was interesting to witness the recent furore surrounding the British Home Secretary Jacqui Smith who inadvertently included the price of two pay-per-view ‘adult entertainment films’ on her parliamentary expenses claim form. There was outrage (although, as Will Self pointed out in his London Evening Standard column, this outrage was peculiarly polite, just in case the outraged themselves were found to enjoy similar entertainments). Pornography aggravates people, whether they condemn it or use it (or do both), because it destroys the normally excepted metaphor quota. It is all metaphor on one level, but, dangerously, it also pierces the metaphorical shield; it presents real events, actually happening. The novelist J.G. Ballard knew the powers of pornography well and said in his notes to The Atrocity Exhibition that ‘the sexual imagination is unlimited in scope and metaphoric power… In many ways pornography is the most literary form of fiction – a verbal text with the smallest attachment to external reality, and with only its own resources to create a complex and exhilarating narrative’. The form simultaneously resembles everything and nothing but itself. Ballard goes on to state: ‘pornography is a powerful catalyst for social change’. Reason enough for the moral majority to want to see it buried.

The problem with metaphor is its viscosity; it sticks to everything. Paul Ricoeur, in his classic study The Rule of Metaphor, states: ‘to explain metaphor, Aristotle creates a metaphor, one borrowed from the realm of movement; phora… is a kind of change, namely change with respect to location… metaphor itself is metaphorical because it is borrowed from an order other than that of language’. In other words, you can’t fight metaphor from within and you can’t approach it from without. We are all metaphorical beings, and I know, without reading back over a single sentence, that this piece of journalism will be dripping with the stuff.

All of this has major implications for music and for the words used within and around the art form. If music is often seen as special because of its freedom from the directly semantic burden, does this mean that it is unproblematically metaphorical or even meta-metaphorical? Sadly not: the fictions that pertain to the novel are just as insidiously prevalent in music. It isn’t surprising that the classical music concert audience is stuck in the nineteenth century with its endless Beethoven and Schumann cycles. Put simply, these canonic compositions offer the most appealing fictions for our individualistic times, since they tell the story of the subjective mind imposing itself on societal conventions, thereby reinforcing those conventions in a different guise.

Composers who work against this with the wrong, or the most unappealing metaphor (think Stockhausen’s cosmic/alien predilections), or who concentrate on the reality of the performing moment at the expense of content (think John Cage’s ‘empty’ 4’33’’) are seen as deviant by a majority of the concert-going public. Like pornographers, these composers fail to play the game and refuse to reinforce the myth. Metaphor is in us and all around us, but perhaps, like salt in our daily diets, we should either be wary of its use or celebrate it for its own sake. To be aware of its intoxicating presence is the important thing. I offer four examples (below), two lyrics, two musical beginnings. Ex. 1 is all associations and depictions; Ex. 2 presents a more matter-of-fact romanticism; Ex. 3 is consonant, simple and conciliatory; Ex. 4 is detailed, difficult and assiduous. Could a judgment on the worth of these excerpts be made by measuring their understanding of metaphor?

Ex. 1 – Bob Dylan, ‘Beyond Here Lies Nothing’

Well I’m moving after midnight

Down boulevards of broken cars

Don’t know what I’d do without her

Without this love that we call ours

Beyond here lies nothing

Nothing but the moon and stars

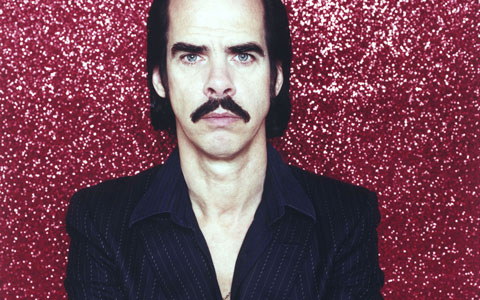

Ex. 2 – Nick Cave, ‘The Ship Song’

Come sail your ships around me

And burn your bridges down

We make a little history, baby

Every time you come around

Come loose your dogs upon me

And let your hair hang down

You are a little mystery to me

Every time you come around

Ex. 3 – Opening bars of Hymn II from Sir John Tavener’s Hymn of Dawn

Ex. 4 – Opening bars of Brian Ferneyhough’s Second String Quartet

Here’s the central problem: as artists we want to make music as relevant to life as possible, we want music to extend its reach beyond its conventions. As listeners, we want to delve into the conventions of music in order that they may tell us something relevant to our lives. Metaphor is the means of exchange. And we see radically different approaches when we consider, somewhat randomly, writers such as Bob Dylan, Nick Cave, Sir John Tavener and Brian Ferneyhough. Each of our examples finds its own metaphorical level. Dylan’s use of language is transparent. His new song, ‘Beyond Here Lies Nothing’, is about love and loss, unsurprisingly, but he creates room for an immersion in rhythm ‘n’ blues structures. Dylan here sings the blues and taps into universal musical concerns. Cave is altogether more opaque. Using the strictures of rhyme and meter as a starting point, he extends himself towards the listener through poetic musings, using variations of the everyday metaphors we see and hear in the media. Tavener’s metaphors, likewise, are on the surface of his music; the unison playing of solo flute, violin and harp makes the attempt to journey into the hidden structures of the piece all but redundant; the message of love and harmony is direct and unbridgeable. Ferneyhough’s Second String Quartet, with its explosive opening bar, and its silent but active countermeasure, displays the mechanisms of its working from the start: materials are compounded and made volatile and the surface meaning is far from clear.

Which of these examples is the most successful in delivering its message? There are no ready answers, but we could perhaps move forward on this assumption: that writers/composers of successful lyrics and music will be conspicuously aware of the amount of metaphor in their art.

Published on 1 June 2009

Peter Rosser (1970–2014) was a composer, writer and music lecturer. He was born in London and moved to Belfast in 1990, where he studied composition at the University of Ulster and was awarded a DPhil in 1997. His music has been performed at the Spitalfields Festival in London, the Belfast Festival at Queen’s and by the Crash Ensemble in Dublin. In 2011 the Arts Council acknowledged his contribution to the arts in Northern Ireland through a Major Individual Artist Award. He used this award to write his Second String Quartet, which was premiered in 2012 by the JACK Quartet at the opening concert at Belfast's new Metropolitan Arts Centre (The MAC). Peter Rosser also wrote extensively on a wide range of music genres, with essays published in The Journal of Music, The Wire, Perspectives of New Music and the Crescent Journal. He died following an illness on 24 November 2014, aged 44.