This is Serious

Simon Cowell

So much has been written of The X Factor, but little of it has achieved balance. Polarised description of the TV show posits addictive light entertainment on one side, and cultural opprobrium on the other. But if The X Factor really does spell the end of intelligent public discourse, why do such large numbers of seemingly intelligent people tune in week-on-week? How has the show both secured and bypassed kitsch, and how has it maintained a stranglehold on serious and casual viewers alike? If one thing is now certain of the phenomenon, it is that it suffuses everything: viewing figures of seventeen million in the UK and Ireland alone advertise its universal allure. The show has grown to be a public axiom, and as such it demands to be taken seriously; carping at its palpable cheapness and camp is not helpful. This article is an attempt at such seriousness.

Thoughtful responses to The X Factor see the programme as a Leviathan that obstructs the public space with baroque nonsense, a Leviathan that is almost impossible to oppose. And much of that is true. The X Factor inexorably saturates. It absorbs everything: critique, assent, dissent, public opinion and music. To adapt a phrase from the writer Mark Fisher: The X Factor seamlessly occupies the horizons of the possible. The idea of the public sphere – as developed by the German philosopher Jürgen Habermas – involves a space of critical discussion open to all that is directed at the social good. This public sphere is made possible by The X Factor, and it is turned ridiculous in the same breath. The useless discourse which busies so much of the programme thwarts at almost every point the possibility of difference: dream-lurid streams of images and overbearing snatches of Carl Orff indicate the typical attitude of the show, which tries to deny of its audience any power of thought beyond a heated passivity.

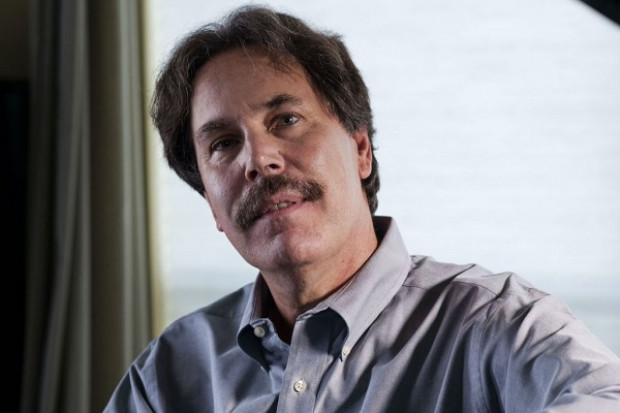

The equivalence between neo-liberalism and The X Factor is obvious. Nowhere is the cold calculus of capital and votes more palpable than in Simon Cowell, the show’s creator, producer and lead judge. For Cowell, creativity is almost-neuter; blandness and affirmation are the criteria he crassly and unanimously applies. Cowell’s notion of creativity is rigid, sclerotic even, showing only the dimmest awareness of the truth and the confusion that lie beyond all surfaces. This was most evident at two telling points in the last few months. The Dublin twins John and Edward first appeared to be farcical rips in the continuum of product that The X Factor tries to narrate. Cowell looked genuinely bewildered, and displayed his contempt openly. But – the loud bottom line. It soon became clear that the twins couldn’t be dismissed as hopeless products. Their shambolic appeal had to be reckoned with for what it was: revenue potential extraordinaire. The story of how Cowell came to love ‘Jedward’ is the story of how capital, given enough time, consumes even that which appears to be inconsumable. By the end, Cowell was voting to keep them on, relishing the notoriety they brought. And with notoriety, of course, the bottom line.

The second event that revealed Cowell’s nature was more compact, but even more chilling. Jon and Tracy Morter’s much-publicised efforts to get Rage Against The Machine’s ‘Killing in the Name’ to be the 2009 UK Christmas number one single (an effort that was misguided at best, though full of good-intention) was an attempt to defy the culture propagated by The X Factor. But it, too, experienced a Cowell turnaround. Initially dismissing the campaign as ‘stupid’, after their victory, Cowell, full of good humour, gave hearty congratulations. Without irony or any sense of satire, he offered them jobs within his company.

The decay of the public sphere which is so cruelly satirised by the all-consuming black matter of The X Factor is exemplified by the show’s production style, which seems hell-bent on turning what might potentially be a critical public into a passive consumer public. The X Factor has generated a public space where true debate is supervened by polarised opinion: the show’s reception is defined above all by the appearance of dispute. This dispute-effect tallies either for the meagre breadcrumbs of capital’s tightly wound consumer mechanisms (Rage Against The Machine at number one), or, alternatively, for the jockeying of position within the snakes-and-ladders fan identification of the show itself.

Yet this account of the discursive atmosphere spawned by The X Factor fails to describe what comes before it, the engagement with the actual thing itself. And I am not ready to view the public in such dark terms as are implied in most of the other accounts of the programme. The X Factor has worrying and cruel elements, no doubt, but I don’t believe that it is necessarily because of these that such a large number of civilised people tune in every week. It is not because of the crass stings, the huge glittery fanfare for the judges, the ridiculous introductions for each of the performances, the straitened musical diet of broadly karaoke-sucrose homogeneity, the unbelievably non-instructional judges’ comments, the incorrigibly stupid musical instruction, nor the dearth of ambition that irradiates the notion of fifteen-million-watching-and-this-is-what-we’re-going-to-show-them! No, I suspect that it is largely in spite of all these things that the programme succeeds.

It is, quite simply, in the intensity of the public’s collective gaze that The X Factor’s greatest quality lies. People keep watching for the gratification they gain from the rare experience of getting to share with such a large network of fellow humans the peculiar sublime of mass narration, empathy, and aesthetics. Aesthetics is the great elephant in the room that never gets discussed, and music is the great winner in The X Factor. The musical regime itself, as I have said, is deeply straitened, and it would clearly be a good thing if the show’s artistic remit were broadened. Yet much of the music, within the given spread of popular song, is perfectly tolerable. A canon of ballads and songs of the last few decades provides the material, and our collective engagement with the contestants, those contestants’ talents and the often-remarkable routines built for each performance do the rest. Music, in its mad and moving exhilaration, weds people to the programme in a strange and seductive way. It is the opportunity to luxuriate in the experience of sharing music and narrative so intensely and with so many – and it is the property of sharing which is music’s great mystery and catalyst – that keeps people watching.

A gentle trance takes place when watching The X Factor. We feel an uncanny sensation of it being live, of it being a spectacle that draws us into a ‘now-ness’. I believe that the spectacle of The X Factor, though defined by fetish and passivity in some senses, is decisively enriched with empathy. Millions of people identify with the human and aesthetic components of the show every week, elements that are amplified by this live sensation.

John and Edward’s sudden thrusting of frailty and difference into the machine-efficiency of the programme, though doomed, is evidence of just such an empathetic engagement. We loved laughing at them, admittedly, but I think it’s reasonable to claim an unacknowledged mass of people cherishing the possibility of humanistic subversion over the baying public that gets depicted by the tabloids. Viewers have a libidinal reaction to the programme which orientates more around music and empathy than it does around image and spite. It’s one way to explain the genuinely talented and captivating Joe McElderry’s 2009 win. But if this is true, how do we harness the sense of community which The X Factor brings? How can we corral that ability to excite people? For it is this libidinal, ethical aspect of the public engagement with The X Factor that provides us with the most vital route out of the mess that the whole loud and shouty thing of X has burnished in the first place. ■

Published on 1 April 2010

Stephen Graham is a lecturer in music at Goldsmiths, University of London. He blogs at www.robotsdancingalone.wordpress.com.