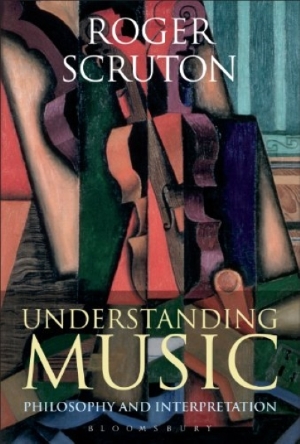

A Book by Roger Scruton

Roger Scruton, Understanding Music – Philosophy and Interpretation

Roger Scruton, who is English, is a Resident Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), a rightwing think-tank in which the likes of Paul Wolfowitz, Newt Gingrich and Richard Perle advocate the robust maintenance of global Western hegemony under the aegis of US imperialism.

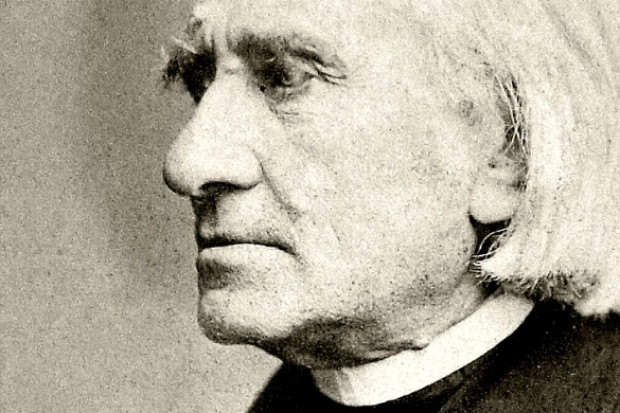

Scruton is also a philosopher of music, whose The Aesthetics of Music (1997) was one of the most significant contributions to the field since Theodor Adorno. The question arises: is there a demonstrable connection between his views on music and his neo-conservative politics? The possibility seems less outrageous in view of Scruton’s authorship of a book called The West and the Rest (2002) in which the theoretical justification of Islamophobia required a misrepresentation of the views of the late Palestinian intellectual – and classical musician – Edward Said (a travesty echoed in this book). Scruton’s views on music, at their most ideological, require similar misrepresentations of Adorno, Arnold Schoenberg and others.

Understanding Music starts from the deceptively simple proposition that ‘[t]he raw material of music is sound’ which ‘relies … on organization that can be perceived in sound itself, without reference to context or to semantic conventions.’ A sound is a ‘secondary object’, ‘an object, all of whose properties are ways in which it appears.’ Sounds are also ‘pure events’, ‘things that happen, but which don’t happen to anything.’

Listening to music, ‘we attend to sequences, simultaneities and complexes. But we hear distance, movement, space, closure. Those spatial concepts … describe what we hear in sequential sounds, when we hear them as music.’ Sounds are heard literally: ‘You hear a succession of sounds, ordered in time, and this is something you believe.’ But we also hear metaphorically: ‘You hear in those sounds a melody that moves through the imaginary space of music.’

However, Scruton’s next move proves that we can also hear ideologically. He approves Wittgenstein’s belief that, in Scruton’s words, ‘musical modernism … involve[d] a mistake about the nature of listening.’ He claims, rightly, that the probability of a dominant in tonal music resolving into a tonic is different to the probability of a G sharp in dodecaphonic music occurring if all other notes of a twelve-note series have been sounded. But he claims without evidence that Schoenberg would view these probabilities as equivalent examples of musical grammar.

He cites the opening of Schoenberg’s Violin Concerto, where the solo violin states the first hexachord of the series, the lower strings filling in the remaining six notes. Correctly claiming that this technical explanation in no way ‘explains’ the musical effect of the passage, he goes on to maintain that ‘those chords on the lower strings are musically arbitrary’. Scruton takes his own deeply-biased subjectivity as sufficient grounds for such an assertion – many admirers of the Violin Concerto will think, and hear, differently.

Scruton implies that Schoenberg picked his series out of a hat, overlooking that he fastidiously chose rows with specific intervallic properties appropriate to each work. The ‘atonal’ habitus, therefore, functions differently from that of traditional tonality which is common to all tonal works, hence the listening-process is necessarily just as different. It may take repeated hearings to convince us that there is nothing ‘arbitrary’ about Schoenberg’s choices, but with familiarity the pitch-relationships within a masterpiece like the Violin Concerto take on an aura of necessity. The relationship between dodecaphonic procedures and musical grammar is open to analysis and discussion, but this is not what Scruton provides.

For Scruton tonality is ‘a paradigm [his stress] of musical organization’ and Schoenberg the wicked wolf who sought its destruction. That Schoenberg believed ‘there is still plenty of good music to be written in C major’ isn’t mentioned, nor that he kept on writing tonal music. Scruton repeatedly and illicitly attributes to Schoenberg views more characteristic of Adorno, whom the composer came increasingly – usually unjustly – to execrate.

Further, it appears that by ‘tonality’ Scruton doesn’t actually mean tonality. In crowning Janacek as an ‘authority’ to replace Schoenberg, he claims the Czech composer demonstrated ‘that tonality must be severed from the architectonic project’ of the tonal tradition. But such strategies, uninfluenced by Janacek, have become typical of most radical music since at least 1970, around which time Ligeti – unmentioned here – proclaimed an end to ‘the tonal-atonal dualism’ and composed avant-garde pieces built almost entirely on diatonicism. The severing of the constituents of a system from the system itself is an anarchic process utterly remote from the ‘defence of traditional order, social hierarchy and the inheritance of Western culture’ that Scruton celebrates elsewhere in the book.

Adorno’s ‘blanket condemnation of the American tradition of popular song’ is equated with ‘his criticism of the capitalist economy’, as if the patent wrongheadedness of the former automatically refuted the latter. While Adorno knew a great deal about capitalism, he was as ignorant of what he inaccurately called ‘jazz’ as Scruton is of contemporary music. Scruton’s description of American song as ‘the musical expression of consumer sovereignty’ blossoms into a hymn to ‘small-town America’ where, apparently, there is no bourgeoisie because ‘the division between owners and producers makes no sense in a place where everyone is both.’ Coming after a condemnation of Adorno for his ‘implied’ utopianism, this idyllic fantasy is bizarre.

Reverting to my original question, it now appears that for Scruton traditional tonality embodies the values of Western capitalist democracy – a view similar to Adorno’s. The difference is that Scruton and his AEI colleagues believe that perpetual war is justifiable in the defence of these values. Those who believe that tonality has a future but who reject the ‘clash of civilisations’ would do well to be critical of such theories.

Adorno and Scruton both demonstrate that whole areas of musical history may become occluded for the obsessive ideologue. In each case, the lucidity with which they write about what they love leads us to regret such occlusion all the more. In Scruton’s case, the magnificent essay on Wagner’s Ring which forms the longest chapter of Understanding Music demonstrates what he is capable of when he sticks to the matter at hand. The rabbit he finally pulls from his hat – a Kantian Wagner – is almost worth the price of admission.

Published on 1 October 2009

Raymond Deane is a composer, pianist, author and activist. Together with the violinist Nigel Kennedy, he is a cultural ambassador of Music Harvest, an organisation seeking to create 'a platform for cultural events and dialogue between internationals and Palestinians...'.