‘Our media have a great deal to answer for’

Throughout 2014, BBC Radio 3’s Breakfast programme played a work by a British composer every morning, part of a year-long project called ‘Best of British’. It made for an impressive line-up: Britten, Skempton, Bax, Nyman, Elgar, MacMillan, Bryars, Delius, Tippett, Warlock, Purcell, Adés, Walton, Maxwell Davies, Dowland, Birtwistle, Holst, Vaughan Williams, Moeran, Tallis and dozens more. A few Irish composers made the list too: Stanford, Field and Trimble.

These names are actually typical of the station’s content. If a listener to BBC Radio 3 isn’t already familiar with their work, they gradually will be made so. Sixty-nine years after the establishment of the station, the BBC’s commitment to classical and contemporary music, despite constant pressure, remains robust.

A result of this 69-year-old public broadcasting commitment, and the accompanying huge annual Proms festival, is not only an international awareness of the above composers, but that classical music performance is hard-wired into the cultural image of Britishness, even if that image is, for many, simply ‘The Last Night of the Proms’ and Elgar’s Pomp & Circumstance March No. 1. Regardless, this image must make it easier for British classical music to secure state support on an ongoing basis.

And for those who wish to delve deeper into British classical music, there is much more. Throughout the Proms last year there was a focus on the contemporary composers Maxwell Davies and Birtwistle, culminating with an extended primetime interview with both; the three-hour long Saturday morning CD Review often features the work of British composers; lively discussion with composers and classical artists features on the daily drivetime show In Tune; every weekday at midday, Composer of the Week provides insight into the broader world of composers from the earliest times to the present day; and in the evening Late Junction and Hear and Now explore further the world of British composition and the avant-garde. Since 2003, the achievements of British composers have been recognized in the annual British Composer Awards, organised by the British Academy of Songwriters, Composers and Authors.

Remove BBC Radio 3, its 1.8 million weekly listeners (3% of the population) and the Proms from the career path of many of the composers above and the reception for their music today would be very different.

Commitment

Ireland, too, has a radio station with a commitment to classical music, including a record label issuing works by Irish composers, and 289,000 weekly listeners (6% of the population); two state orchestras playing a wide range of work and over a hundred concerts a year; a state-sponsored string quartet; a national concert hall; an annual new music festival in the capital city; support for composers, ensembles and independent orchestras via the Arts Council; a network of regional classical music promoters; a resource centre dedicated to contemporary composition; and several high-quality third-level educational institutions where composition and classical music performance is taught. The Dublin new music scene also has a particularly active community of young composers and musicians, ensembles and production companies.

Taken all together, then, what is the status of Irish classical music and contemporary composition in Ireland today? This question provides ample material for discussion in a new book by Irish composer Benjamin Dwyer, Different Voices: Irish Music and Music in Ireland.

The book is in two parts: a 61-page historical overview of classical music in Ireland from the eighteenth century to the present day, and a section comprising 12 interviews over 178 pages with Irish or Irish-based composers, including Seóirse Bodley, Frank Corcoran, Jane O’Leary, Barry Guy, John Buckley, Kevin O’Connell, John McLachlan, Gráinne Mulvey, Siobhán Cleary, Nick Roth and Dorone Paris, plus an interview with Dwyer conducted by O’Connell.

The interviews are succinct and provide an engaging insight into key works by many of the composers. One is immediately keen to seek out a performance of Seóirse Bodley’s Configurations (‘a groundbreaking work in terms of avant-garde aesthetics in Irish classical music’), or Kevin O’Connell’s String Quartet (‘it’s a huge statement… a major piece by an Irish composer… the musical and psychological range and breadth of the String Quartet are astonishing’), or Gráinne Mulvey’s Akanos (‘an extraordinary tour de force’, ‘the tremendous sense of architecture: it is one huge gesture’), or to attend a street performance by Dorone Paris (‘Music is for thinking – it’s for rethinking… Art is for reflecting what the world actually is, not trying to pretend it’s something else’.)

Dwyer draws his interviewees not only on technical aspects of composition but also their backgrounds, education, influences, the relationship between being a performer and a composer, and also the media and current condition of classical music and contemporary composition in Ireland.

Sound Irish

The interviews, which are in the second part of the book, bolster Dwyer’s arguments in the first part, which otherwise might come across as sour. His disappointment is clear: ‘The enduringly poor reception of art music in Ireland remains frustrating and irreconcilable with the effusive activity that is presently taking place in Irish cultural arenas and international platforms.’

Dwyer presents three main reasons for Irish classical music’s low profile: ‘a calamitous history dogged by English colonial and Irish governmental mismanagement’, ‘there has never been a school of Irish composition’, and, ‘the deeply engrained and persistent notion that anything that is Irish must look or sound Irish’. This has meant that classical music was not embedded in Irish society as a ‘vital cultural asset’.

The ongoing pressure to ‘sound Irish’ – an overhang from Ireland’s historical movements for political and cultural independence – appears to be a particular challenge, and for neglect in addressing these historical obstacles, composer John McLachlan puts it squarely: ‘Our media have a great deal to answer for.’ Or, in Dwyer’s words, ‘Those involved with new music in Ireland express bafflement at [the] situation, as media engagement does not reflect the vibrancy, eclecticism and sheer contemporaneity in the work of composers and performers….’

The picture presented of the status of classical music and contemporary composition in Ireland is therefore a negative one, and if one has an interest in these genres it is difficult not to be sympathetic to this view. Classical music does struggle to find its place in Ireland’s cultural identity (it was entirely absent from the Ceiliúradh/Celebration concert at the Royal Albert Hall last year); very few Irish composers or classical artists have representation with an international agent (I count just four composers and four performers); a recently launched two-year project by the Irish Times and the Royal Irish Academy focusing on ‘Modern Ireland in 100 Artworks’ and covering the years 1916 to 2015 focuses on literary and visual arts to the practical exclusion of music; it is unlikely you will hear an informed discussion of an Irish composer’s new CD on Irish Saturday morning radio; and the chances of hearing a year-long ‘Best of Irish Composers’ project on Marty in the Morning on RTÉ Lyric FM? It would require a serious change of direction for the station.

On the other hand, the persistent cursing of the darkness in the book does become trying when compared to the light-a-candle approach that many young Irish composers today have taken. (It jars also because Dwyer has lit many candles himself, such as the excellent Mostly Modern concerts in the 1990s and 2000s). Dwyer doesn’t interview anyone born after 1970 who grew up in Ireland – Nick Roth and Dorone Paris grew up in London and Israel respectively. The perspective of composers Jennifer Walshe, Dave Flynn, Garrett Sholdice or Anna Murray could be quite different.

Furthermore, Dwyer’s negative comments about Crash Ensemble, a group that has done so much to generate interest in new music in Ireland, seem contradictory given his clamour for more media attention. The music was ‘derivative of the downtown, hipster coolness of New York’s Bang on a Can All-Stars’, ‘the rejection of the intellectual traditions of post-tonal European modernism was de rigueur’, the Arts Council was ‘quick to recognise a commodity potential inherent in much of what was being composed’, and the support given to ‘the Crash phenomenon and satellite projects’ was ‘exorbitant’.

Dwyer’s book also doesn’t satisfactorily address why people should be interested in classical music and contemporary composition in the first place. To those familiar with the genre, its extraordinary range of human artistic achievement, its rich language, its deep influence on all musical development, its societal significance, that such an argument is needed may seem bizarre, but the days of classical music’s pre-eminence are over. Increasingly, it is just one type of music among tens of thousands, and it must address this reality if it is to prosper.

***

Different Voices is one of the more accessible books on contemporary Irish composition, but in a sense, its content provides an answer to Dwyer’s bafflement as to the media silence on certain types of music.

The very nature of contemporary composition means that the interviews in the book can become complex, drawing in a range of artistic and musical references, exploring technical detail, covering broad social movements that require an interest in the world of ideas and cultural development over centuries. This kind of discussion is necessary for a genre that has such a historically long, geographically broad, sociologically complex and musically diverse background.

It is no slight to say, therefore, that much new music needs this context. It is a complex art form, and it requires not only performances and broadcasts, but also an accompanying intellectual artillery of media insight and discussion, and imagination in its presentation through the media. It is not enough to simply have general articles and programmes on classical music, it requires editors and producers who also have a very good knowledge of the genre, and who can seek a higher quality of content and choose people who know what they are talking or writing about.

Jane O’Leary comments, ‘You open the Irish Times and you see pages and pages of pop music articles, different types of music. But where’s the classical music, the contemporary music? It’s almost non-existent. So how can you build up a culture that enjoys music created by Irish composers in the same way that it enjoys the books and the films and the paintings and sculptures? … The people who control the media are not musically educated.’

Classical music’s future

Classical music and contemporary composition, furthermore, need media engagement for their survival. They cover such a range of complex musical forms and sounds, and require such huge resources in terms of education and performance to sustain themselves, it is essential that they have a strong media presence in order to communicate their intrinsic worth to the society that is most often paying for them.

A commitment to classical music is a decision that every society has to make for itself. Britain made it when it established BBC Radio 3 and The Proms. Ireland made that commitment too when it established its classical music infrastructure.

But in the absence of regular and intellectually substantial restatements of the need for such an infrastructure, Ireland’s musical resources seem to come under interminable pressure. As musical life becomes more and more diverse, this pressure may only increase. Can classical music in Ireland develop in such an environment? Hopefully Different Voices will stimulate further debate on this question.

***

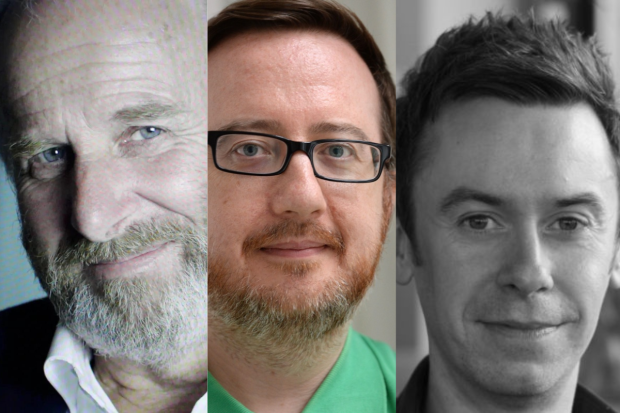

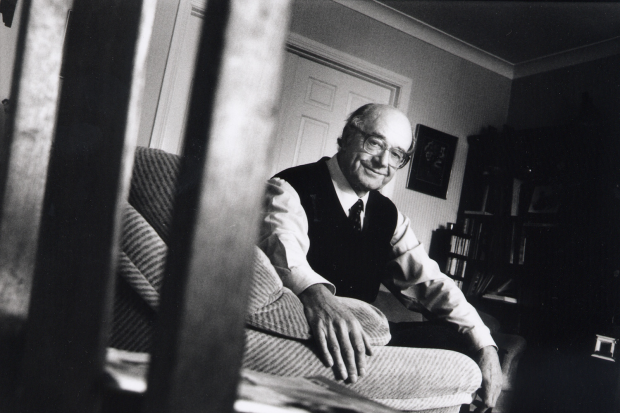

Finally, in the context of a book that emphasises the importance of engaging with new music, it is important to mention that within the last two months, two very fine writers on Irish classical music, and contemporary composition in particular, Peter Rosser and Bob Gilmore, have died too young. They were 44 and 53 respectively. Rosser and Gilmore were champions of independent thinking on music and made a substantial contribution to commentary on Irish music, in the form of articles, essays, podcasts, reviews and books. Thankfully, their work remains and will inform discussion of Irish musical life well into the future.

Different Voices: Irish Music and Music in Ireland by Benjamin Dwyer is published by Wolke Verlag. A website has been produced by the Contemporary Music Centre to accompany the book: www.differentvoices.ie.

The work of Gráinne Mulvey features in an RTÉ National Symphony Orchestra Horizons concert on 13 January at the National Concert Hall, Dublin, at 1.05pm, and new work by Jane O’Leary performed by Concorde can be heard on 25 January at 2.30pm at the RHA Gallery, also in Dublin. The Horizons contemporary music series continues at the NCH with the work of David Coonan (20 January), Philip Hammond (27 January) and John Buckley (3 February).

Published on 8 January 2015

Toner Quinn is Editor of the Journal of Music. His new book, What Ireland Can Teach the World About Music, is available here. Toner will be giving a lecture exploring some of the ideas in the book on Saturday 11 May 2024 at 3pm at Farmleigh House in Dublin. For booking, visit https://bit.ly/3x2yCL8.