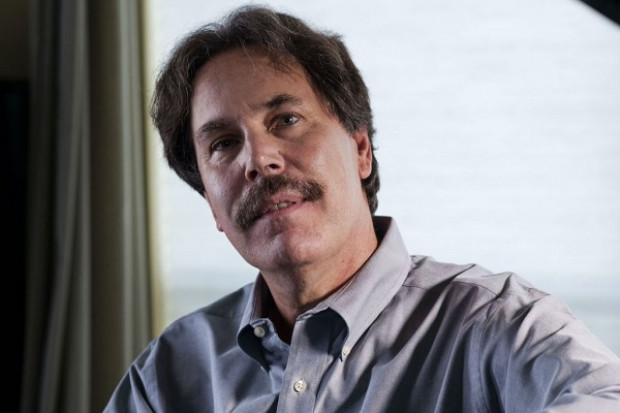

Sebastian Adams

Kirkos Ensemble – Blackout #3

Kirkos Ensemble, directed by Sebastian Adams and Robert Coleman, was founded in 2012 with the intention of exploring new repertoire and innovative concert possibilities. One approach has been Blackout, a concert of mixed new and older compositions, performed, quite extraordinarily, in complete darkness.

This year was the ensemble’s second time using this format, with three concerts and a more total vision of how to bring their audience on a journey. In the third, in July at the RIAM in Dublin, every element from costume to finger food, which was to be eaten at certain points, was designed to enhance one’s engagement, both with the music and the ideas behind it; in this case, the bleakness and darkness of wars present and past, and specifically World War I. The result does more than simply remove the distractions of a brightly lit room; it makes a concert into an immersive event, with every sight, sound and scent given new meaning.

With a sense of ritual, Kirkos and producers Ensemble Music carried their concept throughout all the details of the concert, from the closed door at the entrance and the partly blacked-out programme notes to the silent, masked lantern-bearers leading you on a procession from doorway to venue. Some elements felt slightly overwrought, such as the Halloweenish soundtrack of children’s laughter in the entrance hallway, later giving way to veterans’ voices, or the mime-like make-up of the performers.

The programme was built around a new work by Sebastian Adams titled Harry Patch, inspired by the World War I veteran who was born in 1898 and who died just six years ago; works from Peter Sculthorpe, Johann Froberger, Roxanna Panufnik and Messiaen were chosen to complement the piece. Adams’ work was, in turn, intended to be a counterpart to the first two concerts of the series, Messaien’s Quartet for the End of Time in May, and Different Trains by Steve Reich in June.

Meditation on my future death

Kirkos countered the imposing formality of the Royal Irish Academy of Music room by exploring alternative performing spaces and ideas within it. Requiem (for ‘cello alone) from Australian composer Sculthorpe (1929–2014) was played by Yseult Cooper Stockade through the open doorway from the entry hall. In six movements, and based on plainchant, the work was a personal expression of the requiem, the flurries of the composer’s own voice combining with a more ancient lament. The darkness had the effect of augmenting the audience’s attention to a laser-like focus. It also de-humanises the performers, making the movements and expressions that were visible even more effective, as if an intrinsic part of the music being played.

The solo flute piece by British composer Panufnik (b. 1968) was striking for its simple evocation of the words of Dylan Thomas on which it was based; it was performed by Miriam Kaczor from above the audience on a balcony overlooking the hall. The Baroque harpsichord work, Meditation on my future death by Johann Froberger (1616–67), emerged ghostlike from the darkness without any illumination on the performer (David Adams). Messiaen’s (1908–1992) Appel Interstellaire concluded this section in an incongruous coming together of extremes of technique and sounds on solo horn; performed outside the room, it made the soundworld of the piece seem remote where those of the other works were intimate.

Harry Patch

Though the extreme intensity of the concert was close to exhausting, the immersion in sound also imposed a sense of timelessness, something the composer of the main work of the evening played on to great effect. Sebastian Adams is a young composer (b. 1991) with a strong personal language inspired by the large-scale works of the twentieth-century, and his own experience as a performing violist. Lasting over an hour and comprised of eight movements for piano, cello, flute and horn, Harry Patch is a dark work that toys with the listener’s sense of expectation. Each movement, whether the delicate pairings of cello and flute or the chaotic gestures of the full quartet, brought its material almost to breaking point before it disintegrated again. Frequent changes in instrumental colour make this a restless piece, imbued with frustration without resolution.

Adams took the Messiaen quartet as a kind of framework for Harry Patch, building on its eight-movement skeleton. There are shared moments with the Messaien where the casual listener might struggle to know which was new and which was old. Harry Patch, written with support of a bursary from the Arts Council, was also composed with the theatrical elements of the concert in mind: it begins over the end of Appel Interstellaire, while the horn player is still out of the room, and later a solo horn movement has Hannah Miller make her way from to the stage outside while playing, creating a haunting disembodied military-style voice. Performers are guided to their positions by the lantern bearers’ ritual-like procession, just as the audience were.

Far from being a celebration of the glory and fame of wartime heroes, Harry Patch is about the futility of the eternal fight: Patch himself lived in obscurity, only becoming celebrated for having lived a long time after the war. Not intended as a programmatic piece about his life, Adams’ work instead focuses on the emotions he associates with Patch. The work does feel a little lacking in narrative as it moves from movement to movement. What it has instead was a core of anger, or despair, struggling to find a way to express itself through a haze of smoke and noise, of chaos and turbulence, until it eventually gives up and fades into obscurity, repeated chords on the piano sounding like a slow, dying inhalation and exhalation. As Adams said about his work, ‘…I disagree with Messaien: there’s a real message of hope in his music, but Harry Patch is saying that we’re a century later and nothing has changed.’

Published on 17 August 2015

Anna Murray is a composer and writer. Her website is www.annamurraymusic.com.