Free of Baggage

Kevin Volans: Piano Concerto No. 3

The BBC Symphony Orchestra, Thomas Dausgaard (conductor), Barry Douglas (piano)

Royal Albert Hall, London

22 August 2011

No one writes piano concerti anymore, at least not on the grand nineteenth-century Romantic scale. Rachmaninov was the last to do so between the wars, beating against the tide of High Modernism. Any essay in that direction now would smack of irony, of post-modern pastiche.

Kevin Volans is no glib pasticheur. His Piano Concerto No. 3 (his fourth, actually) is an ‘aspiration’ to that bygone era, and in particular to the idol of his youth, Franz Liszt, whose bicentenary is this year. One forgets that before Volans was invited to Darmstadt in the early Seventies to study under Stockhausen, he began his career as a pianist specialising in the Romantic repertory. Chopin, Liszt and Rachmaninov, not to mention Morton Feldman and the Abstract Expressionist painters, are as much a part of his makeup as the sound world of his native South Africa.

But Volans is sui generis. This BBC Proms commission (I heard it on BBC Radio 3 due to a scheduling mishap), written for Barry Douglas, displays the composer’s uniquely mercurial traits. A one-movement score for two pianos and small orchestra lasting under twenty minutes, this is more a raucous, moody riff on the Hungarian than a concerto per se, or rather his essence: the experimentalism, the atonality, and the dynamics which revolutionised the art of piano performance and interpretation. (Volans defines Liszt as ‘the Father of Modernism’.) Characterised by a solo voice sharp and blunt by turns, a contentious string section, quicksilver passages from the second piano, and interspersed with odd, premonitory silences and drum rolls, the effect is strangely reminiscent of the call and response pattern found in the Blues.

However, this prickly, under-the-skin reminder of where the Blues ultimately came from appears to be more by the way, a welling-up of influences myriad and contradictory absorbed over the years, than intentional. The sources at play in the music of Volans seem, or are made to seem, natural and unforced, as if they came to him, a receptive vessel, and not he to them. This isn’t a matter of being naïve or passive, but of being open-minded, socially as well as artistically, of going with the flow.

Who then is Kevin Volans? Is he the South African who discovered he wasn’t European in Germany or the Germany-returned South African who discovered he wasn’t African? And since 1994, of course, he has been an Irish citizen. Caught between these worlds, neither here nor there, Volans is a free man, free to compose whatever he wants as his friend, the late Bruce Chatwin, first suggested, free of ‘baggage’ as Volans himself put it, another of his ‘aspirations’.

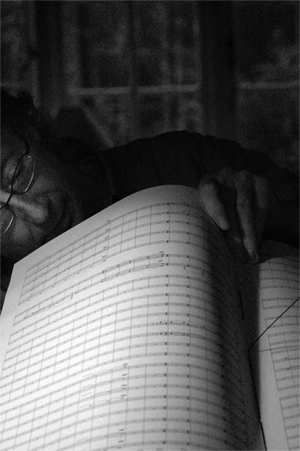

Pictured: Kevin Volans hand-stitching a score of his previous piano concerto, Atlantic Crossing. Photograph: Lucy Clarke.

Published on 30 August 2011

George Rafael is a writer on film and music based in London. He has contributed to Cineaste, The First Post, Opera News, Film Comment and Salon.